NTBG’s Breadfruit Institute demonstrates potential with new collaborations

For centuries, breadfruit has been a vital food crop throughout Oceania. Voyagers carried planting material from the nutrient-rich fruit-bearing tree across the Pacific. Countless generations of farmers have cultivated breadfruit for its versatile, starchy fruits from Southeast Asia and the Pacific, to the Caribbean, Africa, and beyond. Since 2003, when the National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG) established the Breadfruit Institute, interest and awareness for the attractive, long-lived, high-yield tree crop has spread around the world.

The Breadfruit Institute, based at NTBG headquarters in Hawaii, has assembled the world’s largest and most diverse collection of breadfruit varieties (more than 200 trees representing around 150 varieties) on Maui and Kauai. In 2017, with funding from the Hawaii Department of Agriculture and Patagonia Provisions, the Breadfruit Institute began a bold initiative to transform the existing breadfruit research orchard in the McBryde Garden on Kauai into a regenerative organic breadfruit agroforest (ROBA).

Based on the traditions of agroforestry (food forests) practiced throughout the Pacific and elsewhere, the Breadfruit Institute developed the ROBA, a sustainable living model of how a long-lived tree crop like breadfruit can be integrated with a multitude of other edible and ornamental plants to increase productivity while integrating existing resources to enrich the soil and sequester carbon.

Plants such as bananas, taro, sugar cane, ginger, citrus, understory row crops, and others are being grown alongside mature breadfruit trees, producing an abundance of food that can feed people year-round while at the same time, creating more favorable conditions for the surrounding breadfruit trees which produce seasonally.

Through its many partnerships and collaborations, NTBG and the Breadfruit Institute have changed the trajectory of this centuries-old tree crop, infusing new enthusiasm and an interest shared by farmers, chefs, nutritionists, educators, non-governmental organizations, and communities around the world seeking to improve food security, soil health, and environmental conditions.

For five years, Patagonia Provisions has supported the work of the Breadfruit Institute in demonstrating how breadfruit agroforestry can help nourish people and the planet. Now, in collaboration with a breadfruit growers’ cooperative in Costa Rica assisted by the Breadfruit Institute, Patagonia Provisions has produced an exciting new breadfruit cracker that will allow this tropical crop to be easily shipped, shared, and enjoyed no matter where you live.

This delicious, healthful cracker is the latest example of how an ancient, traditional tropical food crop is adapting to meet the needs of the global community. The cracker also illustrates the incredible potential of breadfruit and the important role agroforestry and regenerative organic agriculture can have in creating a healthier, hunger-free planet.

To learn more about breadfruit and agroforestry, and how you can experience and connect with the Breadfruit Institute and National Tropical Botanical Garden, visit https://ntbg.org/breadfruit/.

Tropical Crops Key in the Fight for Food Security

Thanks to a chance encounter in graduate school, Diane Ragone, Ph.D., director of the Breadfruit Institute at NTBG, dedicated her life to documenting and preserving a nutritious, starchy, and storied fruit of the Pacific. Breadfruit, or ulu as it is known in Hawaii, may be the key to preventing the loss of traditional and culturally significant food crops and stabilizing food and economic security in the tropics. NTBG and the Breadfruit Institute are stemming the tide of plant loss and food insecurity with your help. When you donate to the National Tropical Botanical Garden, you’re a part of this critical work that is keeping our plants and our planet healthy.

A Chance Encounter

In 1981, Diane Ragone, a horticulturist interested in tropical fruit, moved to the Hawaiian Island of Oahu for graduate studies at the University of Hawaii in the Horticulture Department. After a chance encounter and single taste of the nutritious, starchy, and storied fruit, commonly known as breadfruit or ulu in Hawaii, Diane decided to make it the subject of a term paper. “The history of breadfruit was so interesting to me because of how widely it was grown throughout the Pacific Islands and how important it was culturally and as a food staple for so many Pacific Islanders for centuries,” she said.

“The history of breadfruit was so interesting to me because of how widely it was grown throughout the Pacific Islands and how important it was culturally and as a food staple for so many Pacific Islanders for centuries.”

Dr. Diane Ragone, Director, the Breadfruit Institute

History and Botanical Interests

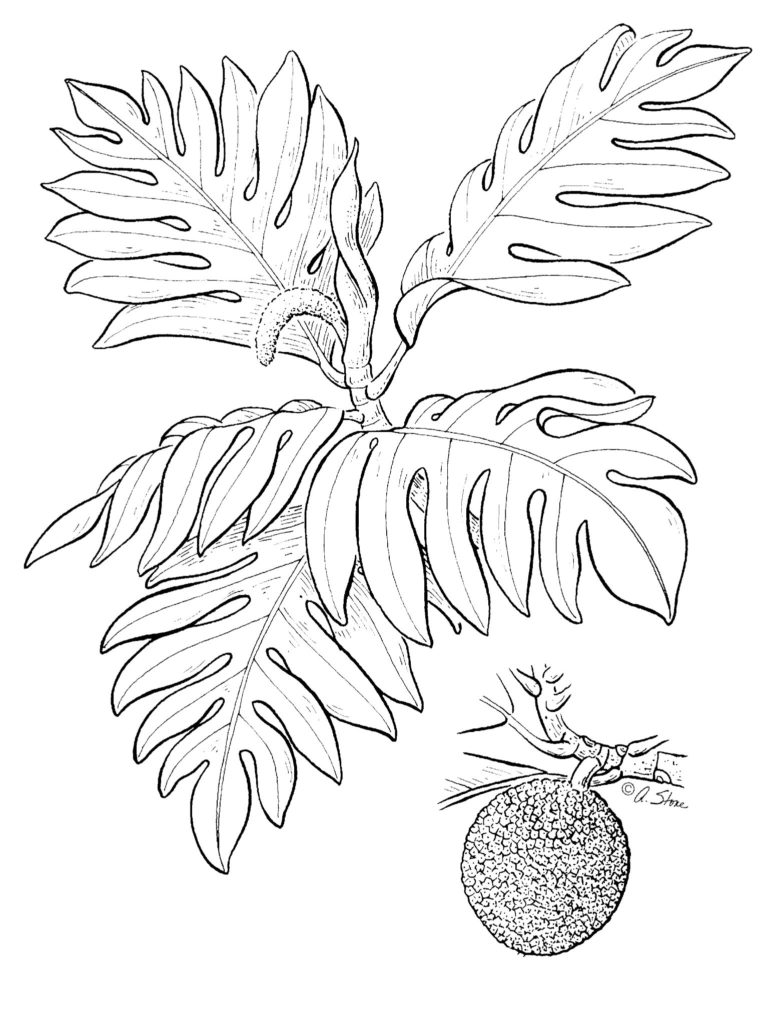

Breadfruit originated in New Guinea and the Indo-Malay region and was spread throughout the vast Pacific by voyaging islanders. Europeans discovered breadfruit in the late 1500s and were delighted by a tree that produced prolific, starchy fruits that resembled freshly baked bread in texture and aroma when roasted in a fire.

Sir Joseph Banks, who sailed on HMS Endeavour with Captain Cook to Tahiti in 1769, recognized the potential of breadfruit as a food crop for other tropical areas. He proposed to King George III that a special expedition be commissioned to transport breadfruit plants from Tahiti to the Caribbean. This set the stage for one of the grandest sailing adventures of all time – The ill-fated voyage of HMS Bounty under the command of Captain William Bligh.

What is little known is that Captain Bligh returned to Tahiti on the aptly named HMS Providence to continue the breadfruit voyage. Several Tahitian varieties, and an unknown variety from Timor, were successfully introduced to the Caribbean in 1793. While many accounts dismiss this epic plant introduction as a failure because the islands’ population did not initially accept this new crop as a food, subsequent centuries have proved the value of breadfruit to the Caribbean and other tropical areas.

A renewed interest in breadfruit emerged in the 1920s and 1940s after World War II when botanists and scientists realized that many traditional food crops and cultivation practices were at risk of disappearing from the Pacific Islands. “Plant introductions were of particular interest to me, so I approached my research from the angle of collection, conservation, and documentation of breadfruit diversity,” said Dr. Ragone. “It was fascinating for me to learn that there were places in the Pacific that had documented 50, 60, even a hundred varieties of breadfruit,” she continued.

In 2003 Diane established the Breadfruit Institute to promote the conservation, study, and use of breadfruit for food and reforestation and is a global leader in efforts to conserve and use breadfruit diversity to support regenerative agriculture, food security, and economic development in the tropics.

Food Security and Economic Opportunity

Compared to an annual field crop, breadfruit trees are easy to plant and can produce anywhere from 300 to 1,200 pounds of starchy, nutritious food every year for decades. Breadfruit grows in tropical regions worldwide, which have some of the highest instances of food insecurity and poverty anywhere. 85% of the places around the world where hunger and poverty are most acute, breadfruit can grow. This makes breadfruit an incredible resource for bolstering food security and creating economic opportunity for the farmers and families where it is needed most.

“Even in Hawaii, it’s hard to be a farmer and make enough money to pay your bills.”

Noel Dickinson, NTBG Research Technician

“Even in Hawaii, it’s hard to be a farmer and make enough money to pay your bills,” said Noel Dickinson, Research Technician at National Tropical Botanical Garden. “What we are trying to demonstrate with the Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforest in McBryde Garden is a way for farmers and individuals in Hawaii and tropical regions around the world to diversify and utilize all of their land with ulu as the backbone of their system,” she continued.

Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforestry (ROBA)

Agroforestry is a farming method that integrates trees, shrubs, and other plants with crops or animals in ways that provide economic, environmental, and social benefits. In 2017, NTBG’s Breadfruit Institute established a two-acre Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforestry demonstration in McBryde Garden with funding from the Hawaii Department of Agriculture and Patagonia Provisions. The demonstration garden contains more than 100 plant species and varieties, which are monitored weekly for production. In 2020, the ROBA demonstration has produced more than 6,000 pounds of fresh food, approximately 20,000 meals, which has been donated to staff, volunteers, and organizations mitigating food insecurity on Kauai during the pandemic.

“One pound of breadfruit feeds 2-4 people,” said Kelvin Moniz, Executive Director of the Kauai Independent Food Bank. “We calculate it by assuming people are putting 2-4 oz. of starch on their plate during a meal. With the breadfruit from NTBG and some other local sources, we handed out one ulu per car and were able to give away more than 200 during one Friday afternoon distribution,” he concluded.

“At first, people were really surprised that we had ulu at the Food Bank, and gradually they have started to ask for it more and more. It is great to see the desire for ulu increase and all of the different ways people are preparing and sharing it with their families.”

Kelvin Moniz, Kauai Independent Food Bank

Nutritionally breadfruit compares favorably with other starchy staple crops commonly eaten in the tropics, such as taro, plantain, cassava, sweet potato, and rice. It is a good source of dietary fiber, iron, potassium, calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium with small amounts of thiamin, riboflavin, and niacin. Breadfruit is gluten-free and a complete protein, providing all of the essential amino acids necessary to human health. “At first, people were really surprised that we had ulu at the Food Bank, and gradually they have started to ask for it more and more,” said Kevin. “It is great to see the desire for ulu increase and all different ways people are preparing and sharing it with their families,” he finished.

Learning from the Past to Farm for the Future

Breadfruit has long been a staple crop and a critical component of traditional agroforestry systems throughout Oceania. There is so much we can learn and apply today from how it has been cultivated throughout history. “Breadfruit agroforestry typifies regenerative agriculture as indigenous people of the tropics have practiced it for centuries,” said Dr. Ragone. “They had no outside inputs, only organic resources provided by the land and sea, so every part of the agroforestry system interacted and worked together to rebuild and add nutrients back into the soil,” she continued. Unlike other starchy food crops, breadfruit does not require annual soil tilling and provides more significant carbon sequestration benefits for the environment, which helps mitigate climate change.

“What is most dear to my heart is local abundance. We need to diversify agriculture in tropical regions, and breadfruit is an important staple crop that can do that while providing local and community self-sufficiency and food security.”

Dr. Diane Ragone, Director, the Breadfruit Institute

Over the last decade, more than 100,000 breadfruit trees have been planted in Hawaii and around the globe thanks to the efforts of The Breadfruit Institute and partners in its Global Hunger Initiative such as the Hawaii Homegrown Food Network, Trees That Feed Foundation, Cultivaris, and many more. Now that individuals, families, and farms have more access to breadfruit, so do entrepreneurs who can develop novel food and products, leading to economic growth. “What is most dear to my heart is local abundance,” said Dr. Ragone. “We need to diversify agriculture in tropical regions, and breadfruit is an important staple crop that can do that while providing local and community self-sufficiency and food security.”

Healthy Plants. Healthy Planet.

From its origins in Oceania to historical expeditions, botanical introductions, and conservation efforts, breadfruit has been on an incredible journey to the modern world. Thanks to generous supporters, partners, and volunteers like you, NTBG and the Breadfruit Institute will continue to study, fuel economic growth, and drive agricultural innovation with breadfruit.

Want to get involved? Donate to the Healthy Plants. Healthy Planet campaign to support NTBG science, research, and conservation efforts today and learn more about opportunities to visit and volunteer. “My husband and I are avid gardeners and learned about the wonders of breadfruit during a visit to McBryde Garden in 2015,” said Anne Cyr, NTBG volunteer. “A later trip to St. Kitts and the West Indies broadened our understanding of breadfruit’s importance, and we signed up to volunteer at the Breadfruit Institute during our next visit to Kauai. We planted taro, harvested, and weighed lots of breadfruit and learned so much! We can’t wait to get back and work beneath the beautiful and bountiful trees again,” she exclaimed.

Give now to support food security and check out these resources, entrepreneurs, and partners for more information on breadfruit.

Additional Resources

An Interview with the Mother of the Breadfruit Movement, Hawaii Public Radio

Breadfruit Institute

Breadfruit Agroforestry Guide

Patagonia Provisions Agroforestry Partners

Global Hunger Initiative

Hawaii Homegrown Food Network

Maui Breadfruit Company

Plant Health by David Lorence

Dr. Dave Lorence, NTBG Senior Research Botanist

The United Nations has declared 2020 as the International Year of Plant Health. In recognition of this timely and timeless theme, and with the understanding that the health that all life on this planet is dependent on plant health, David Lorence discusses how NTBG contributes to protecting and advancing plant health.

Protecting plant health can help alleviate hunger, reduce poverty, safeguard the environment, and boost economic development. However, protecting plant health depends on correctly identifying and naming plant species. If we don’t know the correct names of plants, how can we know what we are conserving? This applies to all plants, not only to those cultivated for food, fiber, medicine, or as beautiful ornamentals, but also countless less well-known species that are essential to the health of natural ecosystems.

Donate to our Healthy Plants, Healthy Planet campaign today!

Help NTBG preserve biodiversity and plant health for future generations. All donations made before December 31 will be matched up to $100,000

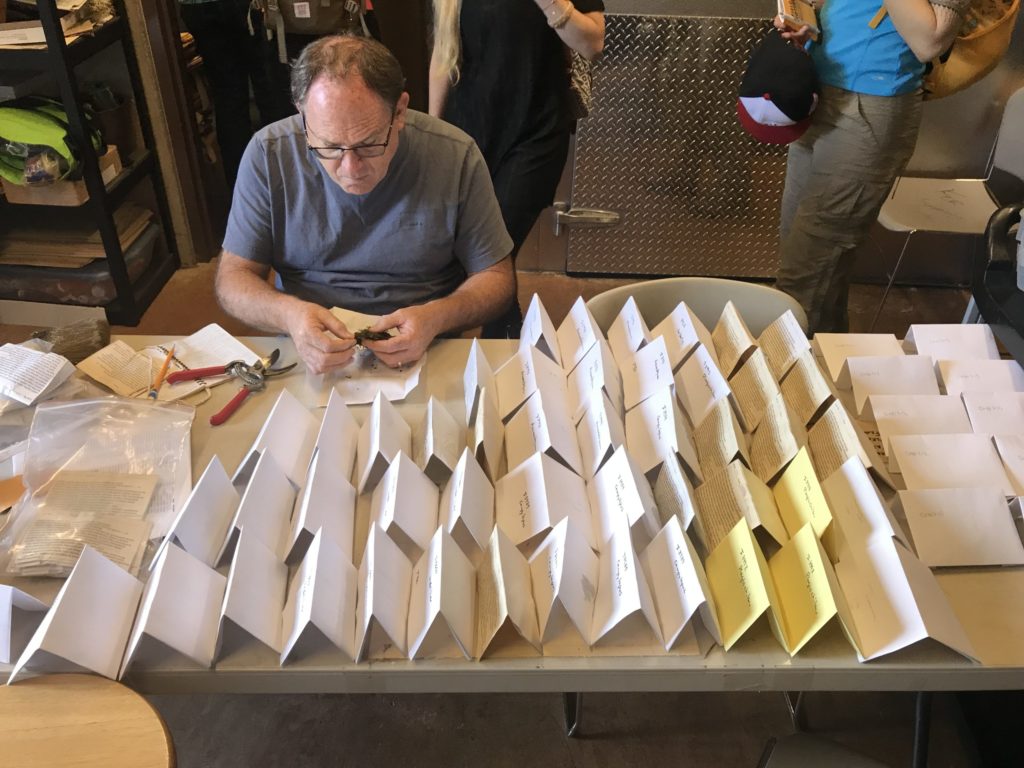

As our planet’s biodiversity faces a grave, growing risk, centers of research excellence in systematics like NTBG have vital role to play. Natural history and plant collections in particular, play a crucial role in research, education, and public outreach. Collections of plant specimens (herbaria) are the foundation for all studies of plant diversity and evolution. A herbarium is a critical resource for biodiversity, ecological, and evolutionary research studies. Herbaria, like other natural history collections, are the essential resources for taxonomy (naming and classification) and the study of biodiversity. A herbarium is like a library, but differs in that the information is stored in a biological form as pressed, dried, and accurately identified plant specimens.

A herbarium is a primary data source of dried and labeled plant specimens that are arranged for easy retrieval access and archival storage. Herbaria may be digitized (as we do at NTBG), making the label data and even images of the specimens available online through databases.

Collectively, herbarium specimens provide enormous economic and scientific returns to society and are irreplaceable resources that must be preserved for future generations. All fields of biological science, from the level of molecular biology to ecosystem science and species conservation, are dependent on natural history collections, not just for application of names, but as the basis for referencing all aspects of biodiversity. These are but a few of the ways that herbaria, and the work we do, help promote plant health.”

Ulu Stuffing Recipe

Add a sustainable and tropical twist to your Thanksgiving stuffing recipe by making a simple swap from bread to breadfruit (ulu or Artocarpus altilis). Not only is it a delicious and nutritious switch, but when you use ulu in your Thanksgiving meals, you support agriculture, food, and economic security in the tropics. This tropical take on the traditional side dish also includes quinoa, which was introduced to the United States world-renowned botanist, David Fairchild, whose former residence serves as the location of NTBG’s Kampong Garden today. This tasty dish also includes macadamia nuts, celery root, onion, and garlic. Add your favorite sausage to spice things up.

Share your completed dishes with us on social media and tag us @ntbg on Instagram.

Ulu Stuffing Recipe

Ingredients

- 1 cup uncooked quinoa

- 2 cups water

- ¾ cup celery or celery root, small diced

- 2 cups breadfruit, cubed and steamed; See notes on preparing and cooking breadfruit below.* Substitute with plantain or any variety of cooking banana if you don’t have access to breadfruit.

- 1 medium onion, chopped

- 1 clove garlic

- 2 teaspoons poultry seasoning

- ¾ teaspoon salt

- ¼ cup fresh parsley, chopped

- ¼ cup macadamia nuts, chopped

- 2 tablespoons olive oil

- Optional: diced sausage

*notes on preparing and cooking breadfruit…We recommend cooking your breadfruit ahead of time! You can even steam a whole, unpeeled breadfruit in a pressure cooker or roasted in an oven to make peeling and slicing easier. Refer to our cooking page for tips. You can also peel and cube raw breadfruit and pan fry with the vegetables the day of. The raw breadfruit will be crispier on the outside, like home fries, whereas the pre-cooked breadfruit will add a softer, more bread-like texture to the dish which works wonderfully in a stuffing! The point at which you add the breadfruit to the pan depends on whether you choose to cook it ahead of time so pay close attention to the directions below to get the desired result.

Cooking Instructions

Step 1

Cook quinoa according to package directions. Set cooked quinoa aside in a large mixing bowl.

Step 2

Heat a tablespoon of oil in a pan on medium-high heat. If you are using the optional raw breadfruit, plantains and/or sausage, add to the pan first and cook, stirring frequently until browned. Once browned, add the garlic, onions, and celery or celery root to the pan. Cook on medium, continuing to stir frequently, until veggies are fork tender, about 15 minutes. Once the veggies are softened, add the steamed breadfruit (if you did not use raw breadfruit), poultry seasoning and salt, stir to coat evenly. See the notes on preparing and cooking breadfruit above for more information.

Step 3

Add the cooked veggies to the quinoa in a large mixing bowl and stir to combine. Mix in chopped parsley, macadamia nuts and olive oil and toss until everything is evenly distributed. Serve and enjoy!

Share your completed dishes with us on social media! Be sure to tag @ntbg on Instagram.

Breadfruit History

“regarding food, if a man plants 10 (breadfruit) trees in his life he would completely fulfill his duty to his own as well as future generations…”

Polynesians brought Breadfruit to the Hawaiian Islands because of the many uses they had for these important trees. Breadfruit trees provided food, medicine, clothing material, construction materials and animal feed.

Breadfruit is an excellent dietary staple and compares favorably with other starchy staple crops commonly eaten in the tropics, such as taro, plantain, cassava, sweet potato and white rice.

Complex carbohydrates are the main source of energy with low levels of protein and fat and a moderate glycemic index. It is also gluten free. 100 g fresh fruit provides 102 calories. Breadfruit is a good source of dietary fiber, iron, potassium, calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium with small amounts of thiamin, riboflavin, and niacin.

The trees are traditionally used and are a major component in mixed cropping agroforestry systems. Breadfruit creates a lush overstory that shelters a myriad of useful plants including yams, kava, noni, bananas and sweet potatoes.

One of the highlights of the McBryde Garden is NTBG’s Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforestry (ROBA) project which acts as a living classroom and 2-acre demonstration project. The data that is collected by our ROBA team is used to advise local farmers on best practices and techniques. This year, our team was able to ground proof ROBA’s productivity and display breadfruit agroforestry’s ability to support community resilience in times of need. So far, over 6,000 lbs. of breadfruit has been donated to local food banks on Kauai!

Additional Breadfruit Resources and Recipes

Community Supported Agriculture

Wondering how to sign up for a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) subscription or where you can buy breadfruit in Hawaii? Check out the links below to find a source near you.

Find Breadfruit Near You

Hawaii Ulu Co-op Breadfruit Locator: https://eatbreadfruit.com/pages/findbreadfruit

Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) and Farm Locator: https://gofarmhawaii.org/find-your-farmer/

USA Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) Locators

Holiday Recipe Challenge

This holiday season, NTBG is challenging supporters to eat locally-grown, seasonal meals in honor of our fall campaign. No matter where you live, your food choices impact your local economy, ecosystem, and public health. Join us by donating to the Healthy Plants, Healthy Planet campaign to perpetuate the survival of plants, ecosystems, cultural knowledge of tropical regions, and support food security worldwide. Explore the recipes and resources below to get started.

Donate to the Healthy Plants, Healthy Planet campaign today!

Help NTBG continue our work supporting sustainable food systems. All donations made before December 31 will be matched up to $100,000

Holiday Recipe Challenge

Taking us up on our challenge? As you make your holiday grocery lists, consider using locally grown, seasonal ingredients. We’re sharing a few of our favorite recipes below for some inspiration.

Show us what you create! Share your images with NTBG on Facebook @saveplants, and on Instagram and Twitter @ntbg. Use the #ntbgrecipechallenge and be entered to win a prize!

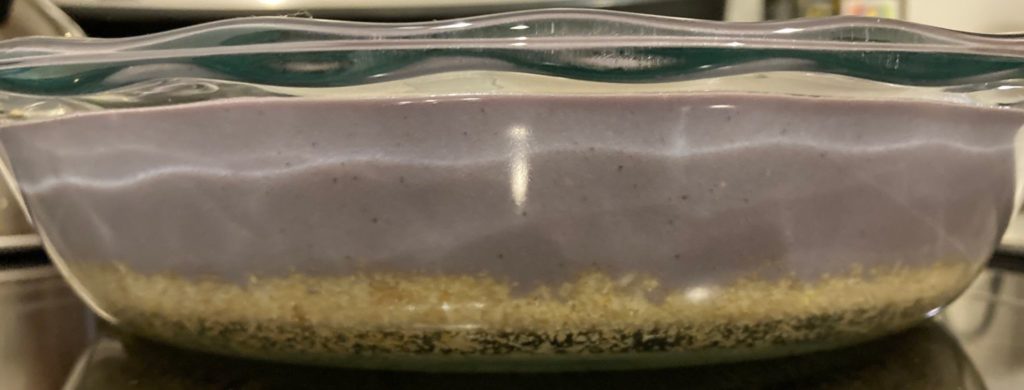

Kalo Pie Recipe

This Kalo Pie Recipe is a Hawaiian inspired take on the traditional thanksgiving desert. Guaranteed to be a hit with your friends and family!

Community Supported Agriculture

Wondering how to sign up for a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) subscription or where you can buy breadfruit in Hawaii? Check out the links below to find a source near you.

State of Hawaii

Breadfruit Locator: https://eatbreadfruit.com/pages/findbreadfruit

Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) and Farm Locator: https://gofarmhawaii.org/find-your-farmer/

USA Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) Locators

How do Sustainable Food Systems Connect to NTBG’s Mission to Save Plants?

Agroforestry is a method of farming that integrates trees, shrubs, and other plants with crops and/or animals in ways that provide economic, environmental, and social benefits. One of the highlights of the McBryde Garden is NTBG’s Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforestry (ROBA) project which acts as a living classroom and 2-acre demonstration project. The data that is collected by our ROBA team is used to advise local farmers on best practices and techniques. This year, our team was able to ground proof ROBA’s productivity and display breadfruit agroforestry’s ability to support community resilience in times of need. So far, over 6,000 lbs. of breadfruit has been donated to local food banks on Kauai!

Agroforestry produces 10% – 60% more crops than monocrop farming and contributes to the restoration of ecosystem function. Commercial monocrop farming typically destroys ecosystems, requires more resources (water, fertilizer, land) and often require liberal pesticide usage. Small, local farms on the other hand often rebuild crop and insect diversity, use less pesticides, enrich the soil, create havens for wildlife, and produce tastier food. NTBG’s work supporting sustainable food systems directly contributes to perpetuating the survival of plants, ecosystems, and cultural knowledge of tropical regions.

Learning from the Past

The Hawaiians have a saying, “He wa’a he moku, he moku he wa’a,” which roughly translates to “the canoe is an island, and the island is a canoe.” Voyagers survived a nearly three month canoe trip across the sea carrying a botanical toolkit that provided everything they needed for survival. Once they made land, Polynesians carefully incorporated this toolkit into the islands’ environment.

Hawaiians understood the fatal consequences of upsetting the balance of an ecosystem and developed a culture that co-existed with the land and even enhanced ecosystem function. Need proof it works? Using agroforestry techniques and sustainable practices, ancient Hawaiians’ food systems supported nearly half million people on the island of Kauai alone. Today, the County of Kauai has a population around 80,000, imports nearly 90% of its food and native plants occupy only a small percent of the land mass.

Today, NTBG adapts ancestral resource management practices to address contemporary conservation challenges and restore health, function, and resilience to the land we manage. This approach is known as biocultural conservation.

An Eye On Plants – Campanulaceae

Bellflower family

PHOTO caption/credit: Critically Endangered Cyanea gibsonii, endemic to Lāna‘i. Photo by Steve Perlman

Growing on every continent except Antarctica, Campanulaceae (the bellflower family), with around 85 genera and over 2,300 species, has covered the earth. From Australia’s delicate lavender Campanula and clusters of Asyneuma in the sub-alpine meadows of the Caucasus, to sturdy Lobelia deckenii on the slopes of Kilamanjaro and tiny Cyphocarpus, endemic to Chile’s Atacama desert, Campanulaceae is a vision of diversity.

Lobelia

In Hawai‘i, where a lone colonizing species of Lobelia landed some 13 million years ago, the wide range of micro-habitats, as well as adaptations to seed dispersal and pollination by native animals, allowed it to branch and evolve into Hawai‘i’s most diverse clade (related plant group). An exceptional example of adaptive radiation, Hawai‘i’s Campanulaceae include native Lobelia plus five genera endemic to Hawai‘i: Brighamia, Clermontia, Cyanea, Delissea, and Trematolobelia. The more than 150 endemic taxa are found on all the high Hawaiian islands except Kaho‘olawe.

Among some taxa, the characteristic curved floral tubes indicate possible coevolution with curved-beaked native forest birds — mostly honeycreepers (Drepanididae) — while the long, tubular, fragrant flowers of Brighamia suggest adaptation to moth pollination.

Along with the loss of Hawai‘i’s native forest birds, genetic exchange and seed dispersal have declined. NTBG Research Biologist Ken Wood recalls frequently seeing Cyanea and Delissea in the 1980s, but says that populations lost in tropical storms often couldn’t reestablish themselves. Today, Hawai‘i’s Campanulaceae, Ken says, are in sharp decline. In addition to storm damage, competition with alien plants, damage from slugs, rats, and ungulates have reduced populations, adding to the problem of genetic inbreeding, resulting in less robust plants.

Over decades, NTBG scientists have discovered, rediscovered, collected, and cultivated Campanulaceae, most famously the moth-pollinated cliff-dwelling genus Brighamia, represented by just two species: Brighamia insignis, endemic to Kaua‘i and Ni‘ihau, and the closely related B. rockii, endemic to Lāna‘i, Maui, and Moloka‘i.

NTBG Conservation Biologist Seana Walsh has extensively studied the breeding system and floral biology of B. insignis, and continues to collaborate with staff at Chicago Botanic Garden to conduct molecular studies of genetic diversity within and among ex situ collections.

Cyanea

Another genus, Cyanea, includes some 70 or more fleshy fruit-bearing species such as Cyanea dolichopoda, endemic to the sheer cliffs of windward Kaua‘i, it was discovered and co-described by NTBG staff but is now believed to be extinct.

Cyanea kuhihewa, previously known only from Limahuli Valley, was thought to have been wiped out by Hurricane ‘Iniki (1992). It wasn’t until 2017 that an NTBG-Nature Conservancy team rediscovered it on private land. Seeds were collected and sent to Lyon Arboretum at the University of Hawai‘i where they were grown into plantlets and carried back to Kaua‘i in test tubes for NTBG to grow and outplant in the Limahuli Preserve.

NTBG has also successfully cultivated Cyanea superba (extinct in the wild) and C. rivularis which has been outplanted in Limahuli Preserve. Currently, Living Collections staff are also growing C. sylvestris, C. hirtella, as well as a number of Delissea.

In 2012, NTBG’s Senior Research Botanist, Dr. David Lorence, co-named and described Cyanea kauaulaensis which grows in the mountains of west Maui. Presently, NTBG is also conducting survey work on Kaua‘i with an undescribed perennial single-stemmed Lobelia which may eventually be identified as a new species.

To see Hawai‘i’s Campanulaceae in the wild, hike Kaua‘i’s Pihea trail leading to the Alaka‘i Swamp where you may find multiple Cyanea species as well as Clermontia fauriei or Trematolobelia kauaiensis growing along the trail.

Presently, NTBG has more than 612,000 seeds from 370 accessions representing all six native genera in storage. Some of those seeds will be used to establish a breeding program for Brighamia rockii which represent populations no longer extant on Moloka‘i. NTBG will try to germinate those accessions to grow B. rockii and cross-pollinate plants by hand to produce genetically diverse seeds that can be shared with the Plant Extinction Prevention program for outplanting in a restoration site on Moloka‘i, the plant’s home island.

Kalo Pie Recipe

Ready to make some local food swaps for your holiday meal? Kalo (taro or Colocasia esculenta) is a great local substitute for your favorite pumpkin and sweet potatoes recipes.

This Kalo Pie Recipe is a Hawaiian inspired take on a traditional desert and is guaranteed to be a hit with your friends and family! If you don’t live in Hawaii, consider purchasing pumpkin or sweet potato varieties from your local farmers market or CSA as an alternative to store bought, canned puree.

Kalo Pie Recipe

Ingredients

Filling

- 1.5 lbs of taro, diced into ½ inch cubes. (Substitute purple sweet potato varieties like Ube or Okinawa if you do not have access to taro)

- ¾ cup granulated sugar

- 1 tsp vanilla extract

- 1, 14 oz can of full fat coconut milk

- 3 eggs

- 1 pinch of salt

- 4 tbsp of flour

Pie Crust

- 5 oz of roasted macadamia nuts, ground

- 3 tbsp of butter, melted

- ½ cup panko bread crumbs

- ¼ tsp salt

- ¼ cup sugar

- 2 tbsp flour

Topping (optional)

- ½ cup sweetened coconut flakes

- ¼ cup of macadamia nuts, chopped

- Whipped cream

Step 1

Add diced taro cubes to a large pot of boiling water. Cover and cook until taro is translucent and fork tender, about 15 – 20 minutes. First time cooking with taro? Check out steps 1-3 of this wikihow page for some important tips.

Step 2

While the taro cooks, preheat the oven to 325 degrees Fahrenheit. Combine all pie crust ingredients in a medium sized mixing bowl. Mix until combined. Pour into a 9 inch pie dish and press firmly to evenly distribute the pie crust mixture into the bottom of the pie dish. Bake the crust until golden brown, 10 minutes. Remove from the oven and set aside. Increase oven temperature to 350 degrees Fahrenheit.

Step 3

Drain the cooked taro and discard the water. Add taro, sugar, and vanilla to a blender and mix until smooth and fluffy. If you don’t have a blender, you can use a potato masher or hand mixer. Transfer taro mixture to a large mixing bowl. Add coconut milk and eggs, mixing until all ingredients are well incorporated. Add salt and flour and mix until combined.

Pour taro filling over cooked pie crust. Bake for 45 minutes – 1 hour at 350 degrees Fahrenheit or until pie is cooked through and the center no longer jiggles. Remove pie and let cool to room temperature before decorating.

Step 4

While the pie cools, toast ½ cup of sweetened coconut flakes and chopped macadamia nuts in a non-stick pan over medium heat, stirring frequently. Top pie completely cooled pie with toasted nuts and coconut. Pipe whipped cream along the edges of the pie right before serving. Slice and enjoy!

Share your completed dishes with us on social media! Be sure to tag @ntbg on Instagram.

Taro Cultivation

Did you know that kalo is one of the world’s oldest cultivated crops? Ancient voyagers traveled to Hawai’i with a sophisticated botanical toolkit which included bananas, coconut, turmeric, sugar cane, sweet potatoes, breadfruit, kalo and more.

Kalo is believed to have the greatest life force of all foods. According to the creation chant (Kumulipo), kalo grew from the first-born son of Wakea (sky father) and Papa (earth mother). Their son, Haloa-naka, was stillborn and out of his buried body grew the kalo plant, also called Haloa, which means “everlasting breath”.

The species is thought to be a native of India. However, it was in Hawai’i that the cultivation of kalo reached its most sophisticated level. Ancient kalo terraces (loi) can be seen in the Hanalei Valley, Kaua’i, and the remains of others are found in remote areas, now uninhabited, such as the Na Pali Coast of Kaua’i.

20th century monoculture made Kalo very susceptible to diseases. Approximately 87 of the more than 400 documented varieties still exist today, with slight differences in height, stalk color, leaf or flower color, size, and corm type. At our Limahuli Garden, staff are restoring an ancient system of more than a dozen kalo lo‘i which archaeologists say is over 800 years old. This colorful plate of kalo is the result of their work!

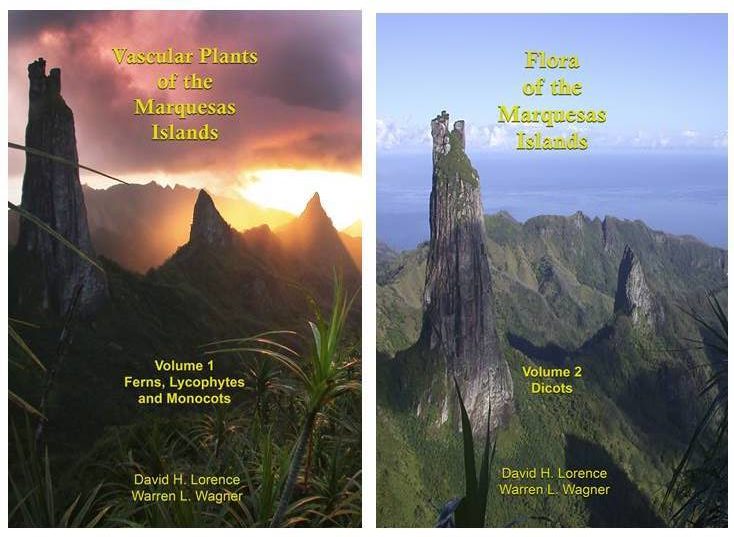

Flora of the Marquesas Islands Vol. 1 and Vol. 2

Flora of the Marquesas Islands, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 Now Available

NTBG is pleased to announce that we have published a major work — the Flora of the Marquesas Islands, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2, which is now available for purchase directly through NTBG. This multi-decade project was spearheaded by NTBG’s Senior Research Botanist Dr. David Lorence and Dr. Warren Wagner, a Research Botanist and Curator of Botany with the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History. The Flora of the Marquesas is a collaboration between NTBG, the Smithsonian Institution, Délégation á la Recherche de la Polynésie Française, and other partners.

This two volume hardbound color book set offers a complete account of all the plants found in The Marquesas Island. Of the 826 vascular plant species recorded, 331 species are native, with the remainder being human-introduced. Nearly half of the native flora (47%) is endemic to the Marquesas and includes 100 ferns and lycophytes. Volume 1 of this two-volume work includes an introduction to the Marquesas Islands, lycophytes, ferns, monocots, and exsiccatae.

Flora of The Marquesas Islands, Volume 1 Lycophytes, Ferns, and Monocots by David H. Lorence and Warren L. Wagner. 415 pages, $60 + tax and shipping.

Flora of The Marquesas Islands, Volume 2 includes dicots, a list of cultivated plants, a list of all literature cited, and an index to both volumes. Comprising 722 pages with 256 color figures and line drawings, volume 2 is available for $70 + tax and shipping.

Flora of the Marquesas Islands, 2 volume bundle set is now available for $100 + tax and shipping.

To purchase, please contact Dr. David Lorence at lorence@ntbg.org.

The Marquesas Islands are a volcanic archipelago of 12 main islands and numerous islets situated within the Polynesia-Micronesia biodiversity hotspot, an epicenter of the current global extinction crisis. Stemming from extensive fieldwork, this book conveys a characterization of the extant floristic diversity, including 85 recently described species, original illustrations, illuminating photos, and critical conservation considerations. This work imparts a foundational knowledge of the flora as a vital component towards preserving biodiversity of the Marquesas Islands.

Pi’ilanihale Heiau

Two decades after restoration, reflections on Pi‘ilanihale Heiau Rising

By Chipper Wichman, Ph.D., FLS, NTBG President with Mike Opgenorth, Director of Kahanu Garden and Preserve

This is a story of restoration, reconciliation, and respect. It’s the story of how NTBG grew as an organization, mended old fences, and built new relationships. This is the story of the restoration of the Pi‘ilanihale Heiau, Hawai‘i’s largest ancient stone structure and a place of deep cultural and spiritual importance.

The Pi‘ilanihale Heiau is a registered National Historic Landmark and, more importantly, it is the piko (cultural center) of Kahanu Garden on the Hāna Coast of Maui’s north shore.

In the late 1990s, the Kahanu-Uaiwa-Matsuda-Kumaewa family, who along with Hāna Ranch, had gifted the land where Kahanu Garden was started, had grown frustrated because NTBG had not completed restoration of the heiau within the originally agreed to time frame.

In February 1997, I was serving as Director of the Limahuli Garden and Preserve on Kaua‘i’s north shore when news came of the sudden passing of NTBG’s director Dr. William Klein. Within days, the Garden’s Chairman of the Board of Trustees called and asked if I would accept the role of Kahanu Garden Director in addition to my duties as Limahuli Garden Director.

As both gardens were in remote communities on different islands, the decision was not easy. Simply commuting from Hā‘ena on Kaua‘i to Hāna on Maui would be demanding, but beyond the travel logistics, there was the question of addressing the complicated and strained relationship that had developed between the Garden and the Hawaiian community in Hāna over the past decade.

The Garden’s promise to restore the heiau was the primary reason the property was given to NTBG and we had not fulfilled our commitment. Although the task before us was daunting, my wife Hau‘oli and I felt as though a voice was calling us to accept the challenge and make things pono (right). Recognizing this unique opportunity to reconcile our relationship with the Hāna community and reassess the role of the Garden, I agreed to become the director. By accepting the position, I knew I was committing to oversee the completion of the heiau restoration, a project that could take three to five years and which would require significant fundraising.

But the biggest challenge was finding the right people to work on this massive project. I immediately thought of Francis Palani Sinenci who I’d met years earlier when he visited Limahuli Garden with a group of Maui elders. After having seen how Francis, who was born and raised in Hāna, interacted with the community and could conduct the traditional protocols of a Hawaiian warrior, I knew Francis had the passion, dedication, and cultural foundation needed to restore Pi‘ilanihale Heiau.

From the outset, Francis and I agreed it was critical for the heiau to be restored by stone masons who were from Hāna. Working with thousands of lava rocks, many weighing a hundred or more pounds, was physically grueling, but embracing this kuleana (responsibility) was also culturally empowering and fulfilling.

Francis put together a crew of men from Hāna that included Jack Kahanu-Uaiwa, and Tony Helekahi, along with two of Francis’s brothers, Peter and Sebastian (Igot). The stone masons worked closely with archaeologists Dr. Yosihiko Sinoto of Bishop Museum and Dr. Eric Komori from the Hawai‘i State Historic Preservation Division.

The restoration of the heiau, with lava rock walls rising 50 feet on the north side, was based on a five-phase plan developed by Dr. Sinoto and bolstered by a quarter century’s worth of initial restoration work conducted by Francis Kikaha Lono, affectionately called “Uncle Blue.”

Uncle Blue was the first employee hired by NTBG to work at Kahanu Garden in 1972 and a direct descendant of the paramount Mōʻī (High chief or King) Piʻilani who lived on Maui in the 1500s. It is Pi‘ilani who is credited with completing a major phase of the heiau’s construction. He is also revered as establishing peace across the island of Maui during his reign.

Pi‘ilanihale Heiau, which had been damaged by decades of grazing cattle trampling the site and the unchecked spread of wild vegetation, was badly in need of restoration. And even as dedicated as Uncle Blue and his family were to rebuilding dry stack lava rocks walls, the effort would require the help of a full crew.

As Uncle Blue, Francis, and the crew began the monumental task before them, they carefully employed traditional cultural protocols when removing rubble, locating niho (foundation stones), and rebuilding the terrace walls. When the crew needed scaffolding, they built their own from material in the garden. As the months passed, the pace of work quickened and the crew’s connection to their ancestors and the heiau strengthened.

Francis noted that only with laulima (many hands) could an undertaking of this scale be successful. In restoring the heiau, he said, he could complete the fifth major stage of Hawaiian life (teaching, farming, building, combat, and heiau restoration) which was the final ‘aho (lashing), that bound together a long life of cultural practices.

For Francis and the others, the restoration was not simply a job. The work was a manifestation of their cultural pride and a physical demonstration of their respect for their ancestors. Fueled by a quiet, inner pride, their work advanced at a rate no one could have foreseen and, in less than a year’s time, the restoration was complete.

On April 10, 1999, Hāna’s community gathered to celebrate the completion with traditional protocols and the chanting of the sacred genealogy of high chief Piʻilani, culminating an effort that had begun nearly 30 years earlier. Today, some two decades after the restoration, we see how the project gave rise to a new period of growth and success. The restored heiau rises high above Kahanu Garden and the surrounding landscape, a silent symbol that reminds us of the sacredness of this most special of places.

Reflecting on all that has been achieved since the restoration, Kahanu Garden and Preserve Director Mike Opgenorth described the garden as a place cared for by generations of those dedicated to aloha ʻāina (deep love of the land). “There is no mistake we are guided by those who came before us. The heiau restoration was the most significant accomplishment since NTBG began stewardship of Kahanu Garden,” Mike said. “We will continue to care for the heiau in perpetuity and increase awareness of the biological and cultural resources that surround us. There is so much to still learn about Piʻilanihale Heiau and all that grows here.”

NTBG at the Forefront of Using Drone and GIS Technology

Learn how NTBG is at the forefront of using drone and GIS technology to advance rare plant conservation and discovery in Hawaii’s extreme terrain. NTBG’s Ben Nyberg sits down for an extensive interview on the latest episode of the In Defense of Plants podcast. Listen here.

.svg)