Flooding in Hawaii Damages NTBG Gardens

On March 12, 2021, heavy rain caused flooding in Hawaii which affected all four of NTBG’s gardens in the state. For both Limahuli and Kahanu Gardens, the amount of rain was not unlike rain events that occur there on an infrequent basis, forcing the gardens’ closure but not creating significant damage. At Limahuli, the enhanced infrastructure installed after the 2018 flood functioned exactly as designed to divert water in a deliberate and calculated fashion.

However, for McBryde and Allerton Gardens on the South Shore of Kauai, the rain caused the worst flood event in more than 40 years. The Lawai Stream rose quickly and flowed swiftly, clogging every culvert with large trees and boulders. Water encroached into areas that had never experienced this type of deluge, including Big Valley and the Thanksgiving Room in Allerton Garden. Trees fell, sculptures and benches were displaced, and the Allerton footbridge was completely demolished and washed onto the beach.

This recent flooding in Hawaii tells us we cannot deny climate change any more than we can deny plant extinction. In the midst of uncertainty, we remain focused on our strategic priorities and embrace our mission of discovery, scientific research, and conservation of tropical plants and ecosystems.

Allerton Garden

Thanksgiving Room

The Thanksgiving Room in Allerton Garden sustained some of the worst damage out of Robert and John’s main garden rooms. Statues were knocked off of their pedestals and the fountain was filled with mud. Ginger in and surrounding the room had to be completely removed due to damage and the gazebo saw structural damage.

Footbridge

The iconic footbridge at Lawai Kai was knocked loose during the flood and is now resting in the bay, completely demolished.

Downed Trees and Debris

Along Lawai Stream, trees are down and debris has gathered along Lawai Kai beach. Garden Director Tobias Koehler poses next to a Monkeypod tree that was uprooted on the westside of Allerton Garden.

McBryde Garden

Eddie’s Crossing

Stream crossings were underwater for several hours and large trees and boulders clogged every culvert.

Hawaiian Life Canoe Garden

CEO and Director Janet Mayfield poses next to a tree pulled out of the stream near the canoe garden stream crossing.

A Changing Climate

Plants are the basis of healthy ecosystems from ridge to reef across Hawaii. The islands have truly unique and diverse ecosystems that provide our communities with a myriad of critical resources.

However, our ecosystems are challenged with rapidly disappearing key native species as a result of invasive weeds, animals and diseases. A predicted changing climate is likely to bring more frequent and severe natural hazards. As stewards of the land, lets come together to protect our natural infrastructures and build resilience through nature-based solutions.

The Kauai Climate Change video series from NTBG’s Science and Conservation team, with support from the County of Kauai, provides a summary view of challenges from a changing climate in the context of the Aloha+ challenges, UN Sustainable Development Goals and Hawaii based Strategies for Plant Conservation.

Common Garden Pests are Invasive Species

By Charly Hotchkiss and Hayley Walcher, NTBG Conservation Nursery Team Members

When you think of invasive species on Kauai, you might think of feral cats predating on native birds, or Albizia trees growing from the coastline to mountain peaks, competing with native plants for space and resources. While invasive species are a huge problem in our wildlands, they also pose a threat here in our conservation nursery. Every day our team combats invasive garden pests of every kind. From invasive snail and slugs species to pests like ants and aphids that hitched a ride to Hawaii on alien plants and animals and have made a home here in the islands. Here are some of the most common garden pests we fight in the nursery and tips for protecting your home garden from them as well.

Ants

Ants are an invasive species often overlooked. There are more than 45 species of ants that have been introduced to Hawaii and pose a threat to our work in the nursery in many ways. Ants reproduce in mass numbers and can cause root disturbance, farm other pest insects like aphids, create nests in hollow branches, twigs, and stems. They can be difficult to spot and are often noticed after damage has already been done. They create nests in potted plants and must be removed before plants can be sent for outplanting.

Rats

Rats were introduced to Hawaii when the Polynesian voyagers arrived. They were stowaways on the canoes that quickly reproduced and thrived. After the arrival of Captain Cook in 1778, other species of rats began to make Hawaii their home including the roof rat, Norway rat, and the common house mouse. All rats are omnivores and cause a plethora of issues in the plant conservation field, not just in Hawaii but worldwide. Rats will debark trees, eat native tree snails and slugs as well as native insects. The seeds of many native Hawaiian plants are a delicacy to rats. They eat new vegetative growth on plants in the nursery and treat our seed flats like a buffet. We put wire cages over most seed flats to protect them from these ravenous intruders. Bait stations are also strategically placed throughout the nursery. Both prevention methods not only use up our time, but cost money.

Lacewings

While most non-native species have a negative impact on our environment and our work in conservation, some can have positive effects. One such creature is the common lacewing. Not originally native to Hawaii, this beneficial insect is a treasure here in our nursery. They are members of the Chrysopidae family which includes 85+ genera all of which are predatory. Their alligator-like larvae are often referred to as “aphid lions” and for a good reason. The larvae can eat over 200 pest insects a week, their favorite being aphids, but they will also eat spider mites, caterpillars, etc.

We often find their eggs on the leaves of native Hibiscus plants here in our nursery. Mother lacewings almost always lay eggs on plants that are currently infested with pest insects, so when their babies are born, there is a feast awaiting them. However, this is a cycle we are able to manipulate in the nursery. When we find unhatched lacewings eggs, we can carefully move them to an area with a pest infestation we are currently battling. When the larvae hatch they are insatiable! By encouraging lacewing activity in the nursery we are able to cut back/limit the amount of pesticides we use to treat for pest insects and help create a healthy balance of pests and beneficial insects.

Tips For Combating Garden Pests in your Home Garden

Slugs. You can easily prevent slugs and snails through applying a bait pesticide labeled for home garden use and following the label instructions. However, if you would prefer the pesticide-free route, there are a few old gardener tricks that work well:

- Place shallow dishes of beer in the garden to attract and trap slugs and snails.

- Scatter eggshells in garden beds or around the base of plants. The sharp edges of the shells prevents snail movement. Meanwhile, as the eggshells break down they provide calcium to the soil.

- Baking soda can also be used as a deterrent on top of the soil or placed directly on the snail during dry weather. Baking soda is a salt and will work as such though like salt, it will not be effective when wet.

- Make newspaper tunnels. Snails and slugs prefer hiding and sleeping in dark narrow places. Take a newspaper and roll it into a “tunnel.” Fasten the edges with tape or paper clips and place in your garden near where slugs and snails frequent. Check your newspaper tunnel for slugs and snails in the morning.

Invasive plants. You can combat those pesky weeds with just a few simple tricks and vigilant weed pulling:

- Weed barrier cloths are a great start to a new garden bed or patch.

- Regularly mulching is helpful in preventing weeds and can be done without purchasing expensive mulch. Use banana leaves or other “green waste” from your garden as mulch to not only buffer against weeds but also replenish your soil with nutrients.

- Planting native plants in your garden is also always a good idea. Choose natives specific to your area and densely plant them in areas you are trying to prevent unwanted weed growth.

- Dense planting in general is a good idea when battling against invasive plants. Borrow agroforestry techniques and densely crop together understory plants such as comfrey, mint, spinach, etc.

General Pests. A garden can be a sanctuary for us, but it can also look like a gourmet buffet to some pest. If multiple plants of one species are planted close together, this can create a “hot spot” for pests, kind of like a billboard saying “Hey, you like peppers, well there’s tons here!”

- Intercrop, or plant multiple species of plants together. Intercropping can confuse and deteriorate searching predators.

- Create a defensive border or intercrop with plants like Marigolds, citronella, lemongrass, verbena, and petunia. Plants like marigolds even release chemicals or smells that can actually deter nematodes away from an area.

- Attract beneficial insect predators with densely planted herbs. Basil, oregano, thyme, lavender, chives, rosemary, mints, catnip, lemon balm, onion, nasturtium, and most culinary herbs can all be densely planted and attract caterpillars, aphids, and mealybugs.

Hawaii Invasive Species You Should Know

February is Invasive Species Awareness Month in Hawaii. As a biodiversity hotspot, much of Hawaii’s native flora is threatened by invasive species and has been in decline for years. Last year, a United Nations report from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) documented the accelerating rate of species extinction worldwide with overwhelming evidence that ecosystem health is deteriorating faster than ever.

With these stunning results in mind, there is no better time than now to learn about the threats Hawaii and tropical regions worldwide face from invasive species. Here are a few to be aware of in Hawaii and simple ways to get involved and help protect plants.

What is an invasive species?

Not all species introduced to a new place are detrimental to their environment. Invasive species are organisms that are not native to a particular ecosystem or region and cause environmental or economic harm to the area. Invasive species are often introduced with human assistance and are harmful to ecosystem health because they quickly adapt to their new environment and reproduce rapidly. Invasive plants, for example, can multiply swiftly and starve native plants of essential nutrients or resources. This results in the entire ecosystem being disrupted since other plants and animals (including humans) depend on native species for food, shelter, and clean water.

Invasive Species in Hawaii

Plants and animals native to Hawaii are unique because of the archipelago’s isolated location. Many species that evolved across the islands did so without threats from predatory species and did not develop defense mechanisms like thorns or toxins meant to deter them. This is one of the reasons many native Hawaiian species can’t thrive when introduced species become invasive.

Red Mangrove

Kauai is home to National Tropical Botanical Garden’s administrative headquarters, Botanical Research Center, Conservation Nursery, and three of our five botanical gardens. The Huleia River is a major waterway in the Nawiliwili watershed on Kauai with a long and significant history documented in Hawaiian stories and chants. Today, the river and surrounding wetlands face severe threats from an invasion of Red Mangrove (Rhizophora mangle). Malama Huleia is a nonprofit organization dedicated to removing invasive mangroves and reestablishing the native wetland ecosystem. By their evaluation, two miles of the riverbanks are 100% overgrown by red mangrove. The increasing mangrove density is threatening the habitat of at least five endemic waterbird species that are considered endangered due to habitat loss.

Clearing the invasive mangrove from the river and surrounding wetlands isn’t just crucial for restoring habitat for endangered birds. It also provides an opportunity to replant appropriate native Hawaiian and Polynesian introduced plants. You can help Malama Huleia by volunteering and sharing their work. Monthly community workdays are scheduled on the second Saturday of every month from 8:00 a.m. until 12:00 p.m. Visit the Malama Huleia website for further details.

Ungulates: Invasive Creatures Great and Small

Although fantastic, we’re not speaking of the PBS miniseries, but rather some of the most notorious and destructive invasive species in Hawaii. Ungulates or hoofed animals such as pigs, sheep, deer, and goats pose a significant threat to native plants in Hawaii. These hoofed animals can graze or uproot hundreds of plants in just one night and contribute to soil degradation and erosion. To protect our gardens and preserves, NTBG staff install and maintain miles of fencing to keep ungulates away from restoration sites.

Feral pigs alone have been shown to contribute to habitat loss and endangerment of sixteen Hawaiian honeycreepers – small, colorful birds endemic to Hawaii. In partnership with several national and local experts in the field, NTBG Science and Conservation staff contributed to the recently published research study of the effects of introduced ungulates (feral deer, goats, pigs) on native and alien plant species in the mesic forests of the Hawaiian island of Kauai.

Fungus Among Us

Ohia trees are the most abundant, ecologically important, and culturally significant plants in Hawai’i. They provide food and shelter for native animals and endangered forest birds, facilitate healthy soil development, aid in replenishing aquifers, and are prominent in many Hawaiian stories, songs, and chants.

Nearly ten years ago, ohia trees on the Big Island of Hawaii began dying rapidly. Whole swaths of the forest seemed to wither and die overnight. In 2014, two species of invasive microscopic fungi were identified as the cause of Rapid Ohia Death (ROD). The deadly fungal spores spread easily through the air and invade ohia through broken branches or wounds in the trees. More than 135,000 acres of native forest on Hawaii Island have been affected, and in 2018, the fungal pathogens were also found on Kauai, Maui, and Oahu.

Experts across the state of Hawaii have formulated a ROD strategic response plan. NTBG is part of the team collecting seeds and storing geographically and genetically diverse plant material that can act as a “genetic safety net” and help study resistance to the diseases. As of today, NTBG has 8,612,584 ohia seeds in storage. Staff and volunteers at the NTBG Seed Bank and Laboratory are conducting research and tracking data that will support ohia restoration efforts statewide.

There are five things every individual can do to protect ohia and prevent the spread of ROD in Hawaii:

- Avoid injuring ʻōhiʻa.

- Don’t move ʻōhiʻa wood or ʻōhiʻa parts.

- Don’t transport ʻōhiʻa inter-island.

- Clean gear and tools, including shoes and clothes, before and after entering forests.

- Wash the tires and undercarriage of your vehicle to remove all soil or mud.

Ornamental Invasives

Hawaii is a gardener’s paradise. Unfortunately, many plants introduced for their ornamental value have escaped from home gardens and become invasive in Hawaii. Plants in the Melastomataceae family often have beautiful flowers and foliage but can produce more than 1000 seeds per square meter and grow aggressively, crowding out and overshading native species.

Miconia is one member of the Melastomataceae that is particularly aggressive and considered a noxious weed in Hawaii. Miconia are large trees that can grow up to 50 feet tall and produce large, oval-shaped, two-toned leaves. These plants are native to South and Central America and were introduced to Hawaii as a garden landscaping plant in the early 1960s.

Because Miconia trees can grow so tall and produce large leaves, they shade out native plants and can take over native native forests. The large leaves can also act as an ‘umbrella’ and reduce the amount of water that seeps into the watershed. Miconia also have a shallow root system which contributes to soil erosion and produces thousands of sand-grain sized seeds which are easily spread by birds, small animals and hikers. Miconia was introduced to Tahiti in the 1930s and has taken over two-thirds of native forest threatening 25% of native forest species with extinction.

Landscaping your yard with native species is a great way to combat the spread of invasives and restore your local ecosystem. Native plants provide shelter for local birds and attract bugs and butterflies, which can be food sources for other native wildlife. Check with your local botanical garden and plant nurseries to see if purchasing natives is an option for your community. NTBG’s South Shore Gardens will host a plant sale on February 27, 2021. Shop for plants and meet experts that can help you plant native and keep Kauai safe.

Invasive Species Lists and Resources

Preventing the spread of invasive species in Hawaii and protecting native ecosystems is vital to protecting and preserving biodiversity. For more information on invasive species in Hawaii and ways to get involved, visit the following resources:

How Hawaii Scientists Are Keeping Their Research Alive During The Pandemic

Fewer trips to the field have become the norm as scientists adapt by working from home and connecting with colleagues.

The National Tropical Botanical Garden, the country’s premier tropical plant research center headquartered in Kalaheo, had a lot of exciting plans for 2020. But instead of traveling around the world for international collaborations, NTBG scientists spent this year exploring their own backyard.

Article posted by Honolulu CivilBeat

They’re endangered. They’re endemic.

And they’re coming back.

By Dr. Nina Rønsted, NTBG Director of Science and Conservation

Building on more than half a century of experience, NTBG has become an international leader in the conservation of endangered tropical plants. Partnering with local, state, federal, and private conservation agencies and organizations, our success stories are possible because our field botanists routinely botanize the mountains and valleys of Hawai‘i, other Pacific Islands, and tropical regions on foot, by helicopter, rappelling over cliffs, and using drones to locate, collect, and bring back important field observations and plant collections.

Maximizing the talents of our dedicated staff, volunteers, and like-minded partners, NTBG propagates and grows rare and endangered plants at our conservation nursery on Kaua‘i. Each year we outplant thousands of endangered and endemic species in our gardens and preserves where we can monitor and protect them. Seeds are collected, studied, and stored in our seed bank, and shared with other conservation bodies.

NTBG has collected or co-collected at least 19 endemic taxa which are believed to be extinct in the wild, but still grow in cultivation. Hawaiian species such as Delissea rhytidosperma, Kadua haupuensis, Kanaloa kahoolawensis, Stenogyne campanulata, and others might have gone completely extinct had it not been for our efforts.

Securing the Survival of the Endangered Endemic Trees of Kaua‘i, Hawai‘i

In recognition of NTBG’s ongoing work, Fondation Franklinia, a Swiss private foundation that supports the conservation of globally threatened trees, funded a new project to conserve the endangered endemic trees of Kaua‘i. The project, called Securing the Survival of the Endangered Endemic Trees of Kaua‘i, Hawai‘i, runs from 2020 through 2022. Because Fondation Franklinia specifically targets the conservation of species in their natural habitat, this gave us a unique opportunity to focus on native trees in need of critical conservation. For this project, eleven species were selected which either previously grew in the Limahuli Valley or which still have a remnant population of less than ten individuals.

Monitoring and Collecting in Limahuli Preserve

Knowledge of the historical occurrence of particular species in the Limahuli Valley comes from more than 40 years of monitoring and collecting by NTBG’s science and conservation team. Through these efforts, we have amassed a wealth of information stored in our herbarium and accompanying databases and in technical reports and scientific publications. Pollen profiles of sediment cores have also provided information about past species occurrences, and GIS mapping and potential habitat range analysis helps guide our understanding of conservation needs and opportunities.

The eleven taxa we are targeting for this project are: two species of Hawai‘i’s only native palm genus, Pritchardia limahuliensis and Pritchardia perlmanii; two sweet scented white Hibiscus, H. kokio subsp. saintjohnianus and H. waimeae subsp. hannerae; three lobeliads associated with pollination by nectar-feeding native honeycreepers, Cyanea hardyi, Cyanea kuhihewa, and Trematolobelia kauaiensis; as well as the lesser known Charpentiera densiflora, one of the few tree species in the Amaranth family (Amaranthaceae); also Ochrosia kauaiensis which is a yellowwood in the dogbane family; the curious Polyscias racemosa which produces a long racemose inflorescence with up to 250 tightly packed flowers; and the charismatic Gardenia remyi, a member of the coffee family (Rubiaceae).

Over the course of the three-year project, NTBG will be collecting and propagating seeds as well as using previous collections from our seed bank to balance the need for substantial seed collection of the few remaining plants. When the new treelets are strong enough, most will be outplanted in the Limahuli Preserve in relatively pristine areas or where weed control is ongoing.

To help protect them from seed predation, additional rat traps are being installed in the area. All of this work draws on many skilled science, conservation, and nursery staff from across NTBG, including the help of a full-time project dedicated KUPU member, Matthew Kahokuloa Jr., as part of the KUPU Conservation Leadership Development Program.

The re-introduction of these endangered, endemic trees to Limahuli Valley, where they once proliferated, will reinvigorate wild populations in the Limahuli Preserve where NTBG staff will be able to monitor them long into the future. Conservation collections will also be retained in NTBG’s seed bank, nursery and McBryde Garden. Mature trees representing several of the species are already thriving in the gardens, for example near the South Shore Visitors Center, where visitors may enjoy them up close.

Simultaneously targeting eleven endangered and endemic tree species is a confident step towards restoration of the diversity of native Hawaiian ecosystems. In the race to conserve Hawai‘i’s native forests, every step is critical. While trees are the major part of the biomass, healthy habitat also includes shrubs and herbs, as well native ferns and mosses, many of which also need a prioritized conservation effort.

Alongside the Fondation Franklinia project, and with the support of our members, collaborators and additional grants, NTBG remains dedicated to helping save as many endangered plant species — trees or otherwise — as possible as we work to protect and restore native ecosystems on Kaua‘i and beyond.

Standing up for Trees

Trees are the foundation of forest ecosystems. To date, over 60,000 trees have been named and described globally. Since 2015, a Global Tree Assessment campaign, led by Botanical Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) and the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, has been assessing the conservation status of the world’s trees. This enormous effort has resulted in the assessment of 45 percent of the world’s trees, roughly 38 percent of which are threatened with extinction. This means more than one in five of the world’s tree species faces extinction.

Because of isolation and wide range of climatic zones, Hawai‘i is a global hotspot of botanical diversity. Of the more than 1,360 known native Hawaiian plant species, nearly 90 percent, are unique to the islands. Many species are found only on one island or even a single ridge or valley. Approximately 13 percent of Hawai‘i’s native flora (more than 175 species) are trees. These include Hawaiʻi’s most common and foundational forest trees ʻōhiʻa (Metrosideros polymorpha) which is culturally very important, and koa (Acacia koa).

Hawai‘i also has a high extinction rate with an estimated 10 percent of the flora reported to have gone extinct since the 1840s. Over 50 percent of the species are considered threatened, primarily from the introduction of non-native plants which compete for habitat and destructive animals that eat seeds or foliage. These threats illustrate the importance of the Fondation Franklinia’s Securing the Survival of the Endangered Endemic Trees of Kaua‘i, Hawai‘i project.

Plant Hunters Secure Biodiversity Hotspots

Looking to the Past to Protect Flora of the Future

To protect the food of the future, humans must learn from the past. A secluded garden in Florida preserves a 19th-century culinary curator’s tall tales and botanical introductions, while modern-day NTBG plant hunters in Hawaii use advanced technology to document and save species in biodiversity hotspots. With your help, NTBG is stemming the tide of plant loss and food insecurity. When you donate to the National Tropical Botanical Garden, you’re a part of this critical work that keeps our plants and our planet healthy.

It’s hard to imagine in today’s social media-induced foodie frenzy that the American diet has been anything other than a cultural melting pot of culinary curiosities. However, as Author Daniel Stone writes in his 2018 novel, The Food Explorer: The True Adventures of the Globe Trotting Botanist Who Transformed What America Eats, the same way immigrants came to our shores, so too did our food.

Before the 20th century, much of what America ate was meat, seafood, leafy greens, beans, grains, and squash – nutritious and hearty, but hardly the colorful, flavorful fruits and vegetables easily acquired from grocery store shelves and farmers markets today. Surprisingly, we have one adventurous, botanizing plant hunter to thank for most of the introduced tropical fruit, nuts, and grains that have become prominent parts of the American diet, and he is closely connected to NTBG.

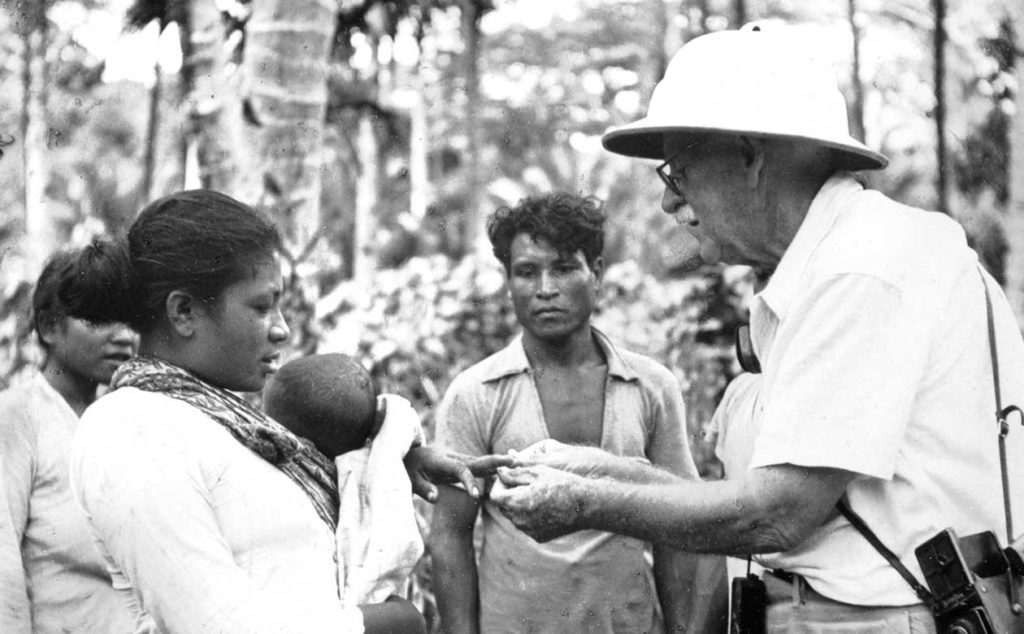

David Fairchild was one of the world’s leading plant collectors in the early 20th century. His private residence in Coconut Grove, Florida, is the present-day location of NTBG’s Kampong Garden. With heritage collections of numerous Southeast Asian, Central, and South American fruits, palms, and flowering trees, The Kampong protects Fairchild’s horticultural legacy and many of his original introductions to the US. It also provides a window into the past that inspires today’s plant hunters and food protectors working toward a more resilient future for our plants and planet.

“The greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add a useful plant to its culture.”

Thomas Jefferson

Fairchild, David Fairchild – International Plant Spy and Man of Botanical Intrigue

David Fairchild was born in the late 19th century and grew up in reconstruction-era America. At that time farmers made up most of the country’s workforce and economic opportunity outside of agriculture was sparse. With a fragile post-war economy largely dependent on farming, The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) feared that an invasive species or natural disaster could easily disrupt the nation’s food supply and created a plant pathology division aimed at diversifying the nation’s agricultural offerings.

Fairchild joined the division after receiving his education in horticulture and botany from Kansas College, and traveled the world as part government food spy, part horticulturalist, part adventurer seeking new food and crops for the expanding American economy and diet. After several years of botanical escapades across Europe, Southeast Asia, Central and South America, he became the chief plant collector for the USDA and led the Department of Seed and Plant Introductions vastly increasing the biodiversity of the nation’s food crops.

Fairchild’s Legacy Today

Chances are, at least one of the beverages or meals you consumed today would not have been possible without Fairchild’s introductions. Avocado, mango, kale, quinoa, dates, hops, pistachios, nectarines, pomegranates, myriad citrus, Egyptian cotton, soybeans, and bamboo are just a few of the thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of plants Fairchild introduced to the United States.

“Fairchild was key to the development of agricultural research and introduction stations around the US and in Puerto Rico. Many of those stations are still current and viable, acting as gene banks for plants he brought into the country,” said Craig Morell, Director of The Kampong. “The Kampong houses some of his early introductions, but these were mostly plants he liked to have in his personal garden. We maintain them today in the same fashion that museums curate and preserve antiquities,” Morell continued.

“Fairchild was key to the development of agricultural research and introduction stations around the US and in Puerto Rico.”

Craig Morell, Director of The Kampong

Fairchild’s work fundamentally changed the American diet and agricultural economy, and his career as a plant hunter, gene banker, and horticulturalist continues to inspire those following in his footsteps today.

Modern-Day Plant Hunters Protect Biodiversity Hotspots

Hawaii was selected for NTBG’s headquarters because of its status as a biodiversity hotspot. This means that while rich in biodiversity, Hawaii’s flora and fauna are deeply threatened by climate change, invasive species, and human activity. While the rate of species loss continues to accelerate worldwide, 2020 was a banner year for NTBG’s modern-day plant hunters. Our team of scientists discovered previously unknown populations of nine rare and endangered species including, Hibiscadelphus distans; Melicope stonei; Schiedea viscosa; Lysimachia scopulensis; Lepidium orbiculare; and Isodendrion laurifolium. Bolstering biodiversity hotspots not only strengthens our food supply, it also builds resilience and ensures ecosystems continue to sustain life, supply oxygen, clean air and water.

“These discoveries offer new hope for conservation of Hawaii’s endangered rare plants and native forests,” said Nina Rønsted, NTBG Director of Science and Conservation. “These findings also illustrate the importance of investing in science as a vital tool to better understand and protect the natural world,” she continued.

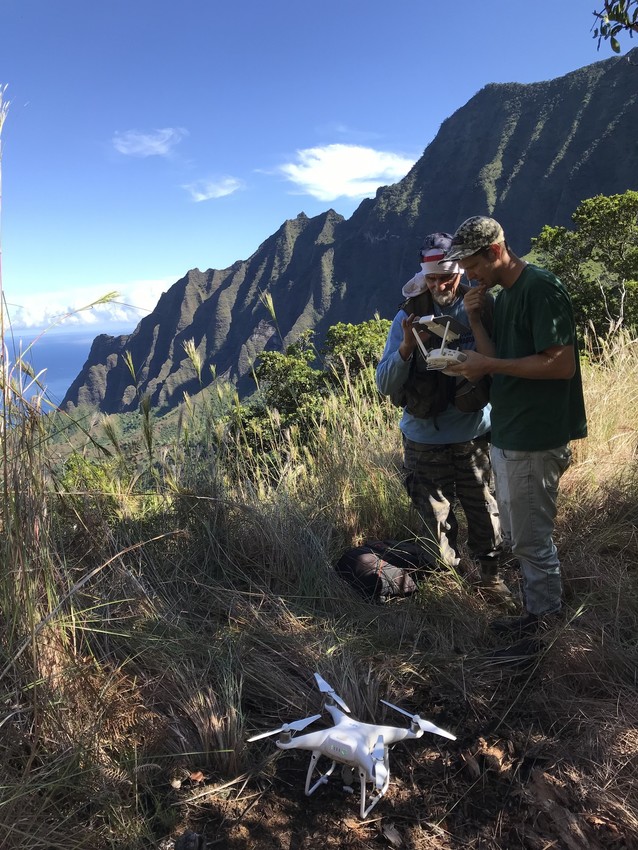

Like Fairchild, today’s plant hunters are no strangers to thrill and adventure. NTBG botanists have long been known for repelling down sheer cliffs and into steep valleys searching for rare plant life. Today, with the help of drone and mapping technology, NTBG remains at the forefront of tropical plant discovery and conservation.

“Hawaii has been referred to as the extinction capital of the United States,” said Ben Nyberg, NTBG GIS specialist and drone pilot. “It’s home to 45% of the country’s endangered plant population, and we don’t know how climate change and new threats like Rapid Ohia Death will affect these rare plants’ habitats. We are trying to document and collect material as quickly as possible,” he finished.

“These discoveries offer new hope for conservation of Hawaii’s endangered rare plants and native forests.”

Nina Rønsted, NTBG Director of Science and Conservation

Keeping Watch

NTBG sets itself apart in the race to save rare and endangered tropical plants. In addition to collecting, categorizing, and seed banking rare plant material, NTBG outplants thousands of rare and endemic species into our gardens and preserves located across the Hawaiian Islands.

From now through 2022, NTBG will engage in a conservation project called, Securing the Survival of the Endangered Endemic Trees of Kauai supported by Fondation Franklinia. This project will focus on eleven species that either previously grew in the Limahuli Valley or have a remnant population of fewer than ten individuals. Throughout the three-year project, NTBG will collect and propagate seeds and use previous collections from our seed bank to balance the need for substantial seed collection. When the new treelets are strong enough, most will be outplanted in the Limahuli Preserve to monitor and protect them. Alongside the Fondation Franklinia project and with the help of our supporters and collaborators, NTBG remains dedicated to saving as many endangered plant species as possible as we work to protect and restore native ecosystems on Kaua‘i and beyond.

From the outlandish adventures and introductions of a 20th-century plant hunter to modern-day scientists using drones to seek out rare plant life on the steep cliffs and rocky ridges of Kauai, NTBG is learning from the past and leading the way in the fight to protect the future of food, plants, animals, and ecosystems. Learn more and support plant-saving science today.

Healthy Plants. Healthy Planet.

NTBG is a nonprofit organization dedicated to saving and studying tropical plants. With five gardens, preserves and research centers based in biodiversity hotspots in Hawaii and Florida, NTBG cares for and protects the largest assemblage of Hawaiian plants. Join the fight to save endangered plant species and preserve plant diversity today by supporting the Healthy Plants, Healthy Planet campaign.

For NTBG scientists in Hawaii, 2020 was a year of finding unknown plant populations

December 15, 2020 (Kalaheo, Hawaii) — Even as the loss of biodiversity and natural habitats accelerates and is worsened by climate change, scientists at the National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG) on Kauai have located previously unknown populations of at least nine species of rare and endangered native Hawaiian plants. NTBG’s Science and Conservation Director, Dr. Nina Rønsted, described the findings as, “a huge step forward in rare plant conservation. For us, this is the best news of the year.” With your help, NTBG is stemming the tide of plant loss. When you donate to the National Tropical Botanical Garden, you’re a part of this critical work that keeps our plants and our planet healthy.

In 2020, NTBG discovered and mapped 11 individual Gouania meyenii plants, a nearly extinct member of the Buckthorn family, reduced to a few plants on Oahu and thought to be gone from Kauai until this new discovery. NTBG and its collaborators at the Department of Land and Natural Resources, Department of Fish and Wildlife and the state of Hawaii’s Plant Extinction Prevention Program, also located two previously unknown Critically Endangered Flueggea neowawraea trees in Kauai’s Waimea Canyon using a spotting scope and a drone.

Additional population discoveries include the Endangered Geniostoma lydgatei, known from less than 200 plants limited to remote sections of Kauai’s wet forests.

Over the course of the year, even as the coronavirus pandemic disrupted human activity on an unprecedented scale, NTBG played a central role in locating populations of other rare plants including: Hibiscadelphus distans; Melicope stonei; Schiedea viscosa; Lysimachia scopulensis; Lepidium orbiculare; and Isodendrion laurifolium — nine species in total.

Rønsted called the population discoveries, “A new hope for conservation of Hawaii’s endangered rare plants and native forests.” She said the findings illustrate the importance of investing in science as a vital tool to better understand and protect the natural world.

“A new hope for conservation of Hawaii’s endangered rare plants and native forests.”

NTBG Science and Conservation Director, Nina Rønsted

This year’s newly discovered populations have been found in isolated, often difficult to reach areas including steep valleys and sheer cliff faces. NTBG is known for its use of roping and rappelling to reach inaccessible rare plants dating back to the 1970s. Since 2017, NTBG has increasingly used drones and other new mapping technology to locate rare and endangered plants so they can be protected and if accessible, seeds can be collected for restoration work.

In 2020, NTBG scientists have been able to continue their work after implementing safety protocols and distancing measures to ensure the safety of staff and partners.

Working independently and in collaboration with state and federal agencies and organizations such as Hawaii’s Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Division of Forestry and Wildlife, the Plant Extinction Prevention Program, and The Nature Conservancy – Hawaii, and others, NTBG has made significant contributions to plant conservation in Hawaii and the greater Pacific region since it was established by a Congressional Charter in 1964.

Learn more about the work of the National Tropical Botanical Garden at www.ntbg.org.

For media inquiries, contact: media@ntbg.org

Simple Banana Recipes

We are sharing a few simple banana recipes you can make and share this holiday season. These dishes were adapted from Hawaiian Cookbook by Roana and Gene Schindler. Buy ingredients from your local farms and farmer’s markets when possible to make these dishes even better!

Share your completed dishes with us on social media! Be sure to tag @ntbg on Instagram.

Banana (Maia) Pudding Recipe

Ingredients

- 2 cups coconut milk (or cow’s milk)

- 2 tablespoons sugar

- 1/4 cup raisins (optional)

- 1 tablespoon chopped macadamia nuts

- 3 medium-size ripe bananas, mashed

Cooking Instructions

- Step 1: Scald milk in the top of a double boiler or thick-bottomed saucepan.

- Step 2: Once the milk is scalding, add sugar, raisins, nuts, and bananas. Cook for 10 minutes, stirring constantly until mixture thickens. Remove from heat.

- Step 3: Divide into individual serving dishes, distributing fruit evenly. Cool and refrigerate. Serve with a dollop of red jam, jelly, or whipped cream. We topped with Papaya Vanilla Jam from Monkeypod Jam, a small preservery and bakery located on Kauai.

Drunken Bananas (Maia Ona) Recipe

Ingredients

- 6 small, firm bananas

- 1/2 cup rum mixed with 2 teaspoons lemon juice. We used Kōloa Kauaʻi Spice Rum

- 1 egg, beaten

- 3/4 cup flaked coconut or chopped nuts (almonds, macadamia, walnuts)

- Neutral oil for frying like vegetable oil

Cooking Instructions

- Step 1: Soak whole bananas in rum and lemon juice for about 1 hour. Turn frequently.

- Step 2: Dip bananas in egg and roll in coconut or chopped nuts.

- Step 3: Heat 1/2 inch of oil in a skillet on low and fry bananas slowly until brown on all sides and tender. Drain on paper toweling and serve hot.

Share your completed dishes with us on social media! Be sure to tag @ntbg on Instagram and use the hashtag #ntbgrecipechallenge for a chance to win a prize.

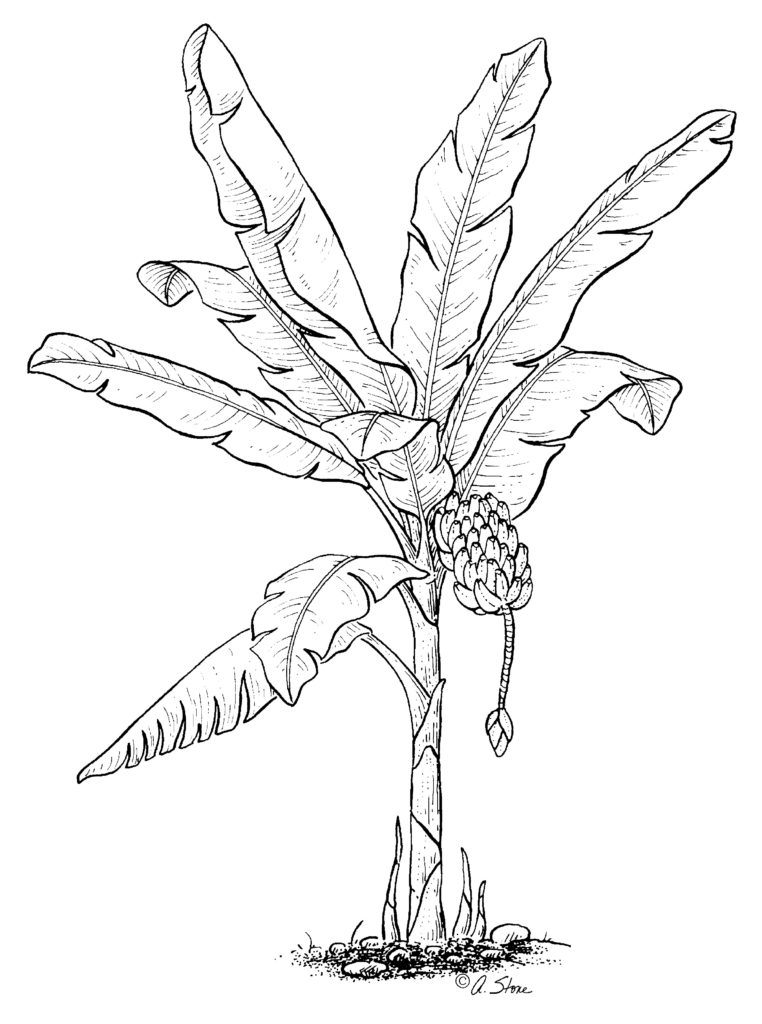

Banana History

Banana or maiʻa in Hawaiian are canoe plants introduced and planted in some of the most idyllic and enchanting places throughout the islands. One ancient story described a banana patch so large you could get lost trying to find your way around it growing deep in Maui’s Waihoi Valley. The story caught the attention of naturalist Dr. Angela Kay Kepler in 2004, and a botanical adventure ensued. Determined to find the legendary banana field, Dr. Kepler hired a helicopter to survey the valley. Sure enough, growing along the Waiohonu River banks, was the largest wild-growing traditional Hawaiian Banana Patch.

After making this discovery, Dr. Kepler phoned Kamaui Aiona, former director of NTBG’s Kahanu Garden and Preserve, managing a small collection of banana varieties. The two returned to the wild patch, collected a pair of young specimens, and returned them to the garden collection where they are still growing. Today, Kahanu’s maia collection exceeds 30 varieties and is one of the most diverse in the State of Hawaii. This collection is essential to the safeguarding the world’s most popular tropical fruit.

Strength in Numbers

A rare collection of bananas at Kahanu Garden safeguards species diversity and the world’s favorite tropical fruit

The world’s most popular tropical fruit is one of the most susceptible to disease. NTBG’s Kahanu Garden maintains a collection of rare bananas that is a safeguard preserving plant diversity of this important tropical food crop and your breakfast. With your help, NTBG is stemming the tide of plant loss and food insecurity. When you donate to the National Tropical Botanical Garden, you’re a part of this critical work that keeps our plants and our planet healthy.

It is a story that is all too common in 2020. A mysterious disease quietly spreads far and wide before its life-threatening symptoms appear. By the time the disease is identified, it’s impossible to stop and takes a heavy toll. While familiar, this story is not about the present COVID-19 pandemic but rather a fungus wreaking havoc on banana crops worldwide and threatening the existence of the most widely consumed Cavendish variety.

If you ate a banana today, chances are you were able to easily acquire it from a local supermarket or cafe. It probably looks and tastes just like every other banana you have ever purchased, and you could find one just like it from nearly any grocer or roadside fruit stand on the planet. This is because monoculture crops of Cavendish bananas account for 47% of global banana production and 99% of bananas cultivated for commercial export.

Monoculture is a form of agriculture focused on growing one type of crop at a time. In the case of Cavendish bananas, not only are they the primary variety cultivated for commercial consumption and trade, the crops are genetically identical. This means that every Cavendish banana you have eaten is a clone of one that came before it. While monoculture does offer the benefit of efficiency and scale, it also increases the risk of disease and crop vulnerability. In other words, if a disease affects one plant, it can affect them all. Banana farmers and barons of the early 20th century are no stranger to the vulnerabilities of banana monoculture. Until the mid 20th century, the Gros Michel variety of banana was the most popular, commercially available variety. Still, fungus all but wiped it out in the 1950s, replaced by today’s heartier, or so thought, Cavendish variety.

A race with no end in sight

Tropical Race 4 (TR4), also known as Fusarium Wilt or Panama Disease, is a soil-borne fungus that enters banana plants from the root, blocks water flow throughout the plant, and causes it to wilt. At present, TR4 cannot be controlled with fungicide or fumigation and has been found in banana-growing regions across Asia, Africa, Australia and was discovered in South America, where most commercial bananas are produced in 2019.

Bananas are the world’s most popular tropical fruit. In fact, the average American consumes more than 26 pounds of banana every year. While not exactly a staple of the American diet, bananas are one of the most economically important food crops worldwide and responsible for an annual trade industry of more than $4 billion, only 15% of which is exported to the United States, Europe, and Japan. What is particularly devastating about the fungus’ potential to overrun our most popular variety is that most bananas are consumed by people in developing countries where affordable food sources and nutrient-rich calories can be hard to come by. With a great demand for bananas and monoculture crops highly susceptible to TR4 and other fungi, scientists are racing the clock to develop new disease-resistant bananas, but looking to history is likely where the answer lies.

Bananas with a legendary past and promising future

Long before westerners arrived in Hawaii, ancient Polynesians voyaged to the islands in double-hulled sailing canoes. To sustain life throughout their journey, and once they reached their destination, they brought a selection of at least two dozen species of plants for food, clothing, structure, medicinal and cultural purposes. These plants are commonly referred to as “canoe plants,” and even though they were introduced to the island, they are an essential part of Hawaii’s cultural history.

Banana or maiʻa in Hawaiian are canoe plants introduced and planted in some of the most idyllic and enchanting places throughout the islands. One ancient story described a banana patch so large you could get lost trying to find your way around it growing deep in Maui’s Waihoi Valley. The story caught the attention of naturalist Dr. Angela Kay Kepler in 2004, and a botanical adventure ensued. Determined to find the legendary banana field, Dr. Kepler hired a helicopter to survey the valley. Sure enough, growing along the Waiohonu River banks, was the largest wild-growing traditional Hawaiian Banana Patch.

“The number of early varieties is a fraction of what it once was, and research to verify each is ongoing. Kahanu Garden serves as a haven where they can be preserved and shared for future generations.”

Mike Opgenorth, Kahanu Garden Director

After making this discovery, Dr. Kepler phoned Kamaui Aiona, former director of NTBG’s Kahanu Garden and Preserve, managing a small collection of banana varieties. The two returned to the wild patch, collected a pair of young specimens, and returned them to the garden collection where they are still growing. Today, Kahanu’s maia collection exceeds 30 varieties and is one of the most diverse in the State of Hawaii.

“In recognition of the threat of losing indigenous crop diversity, NTBG recently adopted a strategic goal to collect and curate all extant cultivars of Hawaiian canoe plants,” said Mike Opgenorth, current Director at Kahanu Garden. “The number of early varieties is a fraction of what it once was, and research to verify each is ongoing. Kahanu Garden serves as a haven where they can be preserved and shared for future generations.” he continued.

Feeding the world starts at home

Today, Kahanu Garden is carrying on the critical work of protecting banana diversity and Hawaii’s botanical heritage and re-introducing these important varieties to local food systems. “Existing commercial varieties do not exhibit the resiliency to combat these new diseases,” said Opgenorth. “It is so important that other banana varieties remain available so that we can defend irreplaceable genetic diversity that will help feed the world,” he finished.

Feeding the world starts at home for NTBG and Kahanu Garden. Together with partners at Mahele Farm, the organizations are working together to provide for the isolated Hana Maui community and share the traditional plant knowledge of Hawaii’s kupuna (elders).

“Over the past ten years, weʻve launched ourselves into the Hawaiian-style study of maia,” said Mikala Minn, Volunteer Coordinator at Mahele Farm. “As small farmers dedicated to feeding our community, the crop variety was a perfect fit for our weekly food distributions. As we shared the fruit and learned the best ways to prepare each type, stories from our kupuna came to light. This personʻs papa would put them in the imu, half-ripe. Another kupuna grew up eating them boiled and mashed. Others made poʻe, a kind of maiʻa poi.,” he continued. Mahele Farm distributes approximately 50 pounds of fresh produce to kupuna at the Hana Farmers market every week and helps maintain a small collection of Hawaiian bananas at the Hana Elementary school.

“This personʻs papa would put them in the imu, half-ripe. Another Kupuna grew up eating them boiled and mashed. Others made poʻe, a kind of maiʻa poi.”

Mikala Minn, Volunteer Coordinator at Mahele Farm

Today’s agricultural and botanical problems are complex, but looking to the past, protecting plant diversity, and encouraging local farmers, schools, and even home gardeners to diversify is an excellent and effective step in the right direction.

Healthy Plants. Healthy Planet.

NTBG is a nonprofit organization dedicated to saving and studying tropical plants. With five gardens, preserves and research centers based in Hawaii and Florida, NTBG cares for and protects the largest assemblage of Hawaiian plants. Join the fight to save endangered plant species and preserve plant diversity today by supporting the Healthy plants, healthy planet campaign.

.svg)