Prof. John Rashford interviewed by Jon Letman

Over the course of his career as a professor of anthropology at the College of Charleston, South Carolina’s oldest university, John Rashford has acquired a well-earned reputation for his boundless sense of curiosity and deep fascination with the relationship between people, plants, and their environment.

Growing up in Jamaica, John developed an early preoccupation with trees. He describes his home island as though it were one great botanic garden, a landscape enriched by the broad diversity of plants introduced from around the world in an age when economic botany was the chief imperial science.

Professor and author John Rashford. Contributed photo

As an undergraduate in the 1960s, John Rashford spent three years traveling the world, observing new places and cultures. While on an extended sojourn across Africa, the would-be anthropologist found himself exploring rugged landscapes dotted with colossal trees with swollen grey trunks like elephants that rose to disproportionately small branches bearing oversized luxuriant pendulous creamy white flowers.

These behemoths were, of course, baobab trees (Adansonia sp.), the iconic arboreal sentinels of Africa’s vast savannahs, abundant and diverse in Madagascar, and revered wherever they grow. Long-lived, and surreal in form, baobab trees have been woven into our collective consciousness, famous from children’s tales (The Little Prince, The Lion King) and imagined as The Tree Where Man Was Born, Peter Matthiessen’s 1972 classic account of Africa.

In fact, it wasn’t until another species of tree (Ceiba pentandra) in the Caribbean was repeatedly pointed out to him — misidentified as a baobab — that John Rashford’s interest in the true baobab grew into what was to become a decades-long endeavor to observe and document what he calls the most conspicuous and useful tree in Africa’s woodlands and grasslands.

Hadza seated beneath a giant baobab tree. Efraim Bar/Alamy Stock Photo

Having studied and written about baobabs since the 1980s, John Rashford has published a book about the tree’s importance to the Hadza, a hunting and gathering society that lives close to nature as keepers of ancient technology, and preservers of an intimate knowledge of the baobab.

John Rashford, now professor emeritus at the Department of Sociology and Anthropology at the College of Charleston, a member of the Linnean Society, former board chair of the Charleston Museum and the Catesby Trust, and a former board member of the Donnelley Foundation, has also served on the Board of Trustees for the National Tropical Botanical Garden since 2009.

From his home in South Carolina, Prof. Rashford spoke with NTBG about his book Baobab: The Hadza of Tanzania and the Baobab as Humanity’s Tree of Life (Springer).

NTBG: How did you decide to dedicate so much time to studying the baobab tree?

John Rashford: I selected baobab because it seemed to encapsulate a lot of the things that I was interested in—human dispersal of plants, Africa, and the links between Africa and India. Why is this plant in the Caribbean and in Brazil when there’s no big discussion of it? It’s still quite an esoteric subject from that point of view.

Madagascar is the center of baobab diversity but your book focuses on Africa and the Hadza people of northern Tanzania. Why did you target baobabs in Africa rather than Madagascar?

The book is on baobabs and human evolution. There’s no indication of a record of early human ancestry in Madagascar. The second thing is there’s a long discussion in the anthropological literature that center of diversity is not necessarily place of origin.

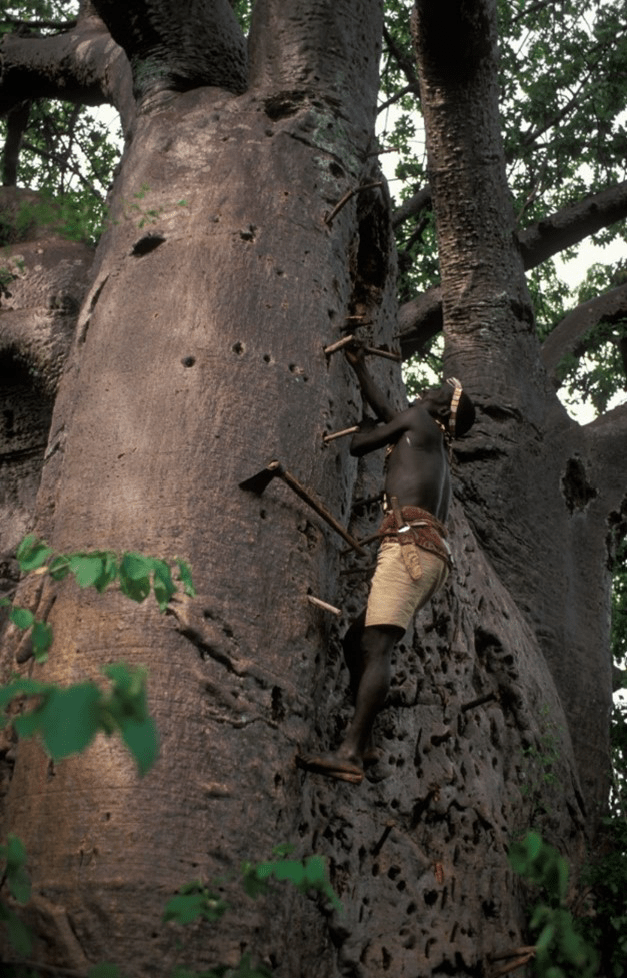

The Hadza use peg ladders to scale the massive trunks of baobab trees to access a variety of resources including honey, fruit, water, and bark fiber. Ariadne Van Zandbergen/Alamy Stock Photo

Since it’s a book on human evolution and baobabs, the choice of Africa and the Hadza was a natural one. They’re a group well known for their distinctiveness and their tenacious history as hunters and gatherers.

How would you characterize this book?

It’s an anthropology book with a research interest in both ethnobotany and ethnobiology, and it is based on the extensive body of literature on the Hadza. It’s the way of documenting how the tree is used by people who are hunters and gatherers in the mosaic savanna environment of human evolution.

You wrote that you first saw baobabs in East Africa as an undergraduate but didn’t develop an interest in the trees until you saw them again in the Caribbean.

I encountered baobab trees in Kenya and Tanzania and again in West Africa. In the Caribbean, I was working on a related species called cotton tree (Ceiba pentandra). Friends took me to see baobab trees which was a surprise for me. I could tell immediately they were not cotton trees from the flowers. It turned out that people in the Caribbean and elsewhere sometimes confuse baobabs and cotton trees.

I kept coming across baobabs in Jamaica, Barbados, the Virgin Islands, Saint Kitts, and elsewhere. I became curious to learn more about the history of the species in the Americas because there wasn’t much information in the literature. Encountering baobab trees in the Caribbean is really what piqued my curiosity to learn more about the species.

The Grove Place baobab in St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands is one of the largest of its kind in the Caribbean. Author John Rashford (center) is flanked by two University of the Virgin Islands faculty (1985). Contributed photo

Were baobabs introduced to the Caribbean and other parts of the world as an ornamental or for some other practical use?

The baobab was probably introduced to the Caribbean not only for its aesthetic value as an ornamental or curiosity, but also for its value as a multisource food tree, its use as a settlement amenity, and its rich symbolic value. There are reports of it arriving in the Americas with Africans who came during the plantation period. This was before French naturalist Michel Adanson wrote his account of the baobab based on his visit to Senegal in the 1750s. He said the baobabs were brought to the Caribbean by Africans and reported correspondence with people indicating that it was in Martinique prior to his description of the tree. The oldest trees in the Caribbean probably date back to the early 1700s before the establishment of the earliest botanical gardens in the region, such as St. Vincent in 1765 and Jamaica in 1775.

Returning to East Africa, can you talk about the connections between the Hadza, baobabs, and honey?

The Hadza are very well known for their love of honey. They obtain it from three primary sources, one of which is the African honeybee which typically builds its hives high up in baobab trees. Not only do the Hadza love honey and regard it as something quite precious, but they also have a relationship to the honeyguide bird.

It’s interesting to note that in their inspirational life, by which I mean their music and dance and storytelling, the Hadza honey collector is also featured as having great significance. So here is a relationship to an important part of their environment that permeates their cultural life.

Baobab wood is relatively soft and because of that, it’s frequently full of holes. This makes it an ideal environment for bees to nest in. But it’s not just bees. A variety of other species tend to set up homes in baobab trees and that’s the basis for referring to it as an ecological tree of life.

For the Hadza, what’s important is the fact that it’s a good resource environment. Whether they’re hunting birds or collecting honey or getting water, all these things are available from baobab trees.

For people who need plant material for cordage, baskets, mats, and other household items, the baobab is a fiber tree that occurs in the drier parts of West Africa and in southern Africa. For some, the baobab is a water cistern, or a vegetable tree appreciated for its edible leaves.

For Hadza hunters, the baobab provides a resource-rich environment. Alamy Stock Photo

Among the baobab’s many uses, what stood out to you as most noteworthy?

I think its aesthetic appeal, its value as a multisource food tree and settlement amenity, and its religious and symbolic significance are by far the most important. The pulp and seeds make a perfect nutritional combination. Clearly, it’s important in the Hadza diet and used as weaning food.

It’s also important as a source of water because it allows people to expand their hunting and gathering range and to access things that they would not be able to access if they didn’t have this additional source of water.

The Hadza do not routinely carry water around with them. They seem to know how to access water wherever and whenever they need it, including in baobab trees. There’s a long tradition in Sudan and South Sudan of using hollow baobab trees as water cisterns. This is much more than an emergency supply. It’s really well integrated into agricultural life, in the case of Sudan, and to hunting and gathering in the case of the San people and the Hadza.

The Hadza don’t manage the baobab for water, but they have a special name for naturally occurring baobab cisterns. They use the woody pod of the fruit to make the containers for extracting the water from the tree. And they use plant fibers to make the rope that lowers the container into the hollow of the tree to extract the water.

My view is that we need a lot more ethnobotanists looking at the question of human evolution and plants because as it is now, there is no outstanding documentation of the fiber plants used by the Hadza. And yet we know that they make a variety of cordage, and we know that cordage is important in their technology for making such things as their bow and arrow, baskets, and beaded adornments.

Can you clarify the primary connection between the baobab and water?

Because the baobab becomes hollow with age, water often collects in its trunk. That’s what hunters and gatherers will access. But it’s related to water in more ways than one, because the fruit of the baobab is also used as a water container. In the book I point out that baobab gourds are traditionally used in Africa for a variety of purposes.

It’s important, as are the use of straws and filtering devices and things for removing bad taste and pollutants from baobab water. All of these are part of the technology of baobab use and water.

My argument is that plants that produce water-handling containers are not that many, even though botanists and ethnobotanists are happy to point to plants that you can access for emergency water supplies—traveler palms, bamboo, and so on. But plants producing ideal containers for every purpose are not that common in nature.

From an evolutionary point of view, it’s interesting that the Hadza do have access to wild relatives of the bottle gourd in addition to the baobab gourd. My point is that early human beings would have used any containers that were available and probably did use relatives of the bottle gourd and the baobab. In the absence of those, ostrich eggshells make a wonderful container as we find among the San of southern Africa. It’s just that it’s rather fragile.

I’ve read of instances where people describe the Hadza picking baobab fruits and using the same fruit pod to collect honey. So, from one tree you can use a gourd to collect water and honey, and you can use it to make the rope to hoist the water gourd.

I think future research that is highly detailed, especially research conducted by the Hadza themselves, will reveal that the tree is even far more intricately intertwined with their lives than I was able to show from the sources that I have reviewed.

Baobab leaves, flower, and seed pod. Contributed photos

Can you talk about the importance of the baobab in today’s world? As we face climate change, loss of biodiversity, pressures on habitat, and so forth, how does the baobab fit into this modern context?

One of the issues I raise in the book is that the tree is of profound importance to the Hadza and now they’re facing competition from fruit collectors for a growing world market in baobab fruits. The baobab has become a commodity. As far as I know, it’s still the case that much of the fruits come from naturally occurring trees even though there are initiatives to develop commercial groves and to select varieties and all the things associated with fruit tree cropping.

Now baobab fruit seems to have made it on its own, referred to as one of the new “super fruits.” The nutritional benefits are always being highlighted. If that’s going to be the case, then they need to develop systematic farming of baobab trees in Africa and not in the way that’s characteristically done where you plant one single genetic strain mile after mile. We know that is environmentally catastrophic. It’s also dangerous to the natural population of baobab trees. We need a new strategy to cultivate the tree, protect the genetic diversity, and not leave it genetically exposed.

Who did you write this book for?

I wrote it for those with a genuine interest in anthropology and the ethnobiological sciences. That’s why it’s heavily cited. I wanted people to know what I had read and where the information came from. There are a lot of people who don’t realize they’re in a position to contribute their own information. I wanted to encourage more research and so I’ve written in a style that makes it more amenable to researchers.

Do you have any final words about the baobab?

Human beings like a well-structured environment that conveys the idea of permanence and continuity. What better way than to have a tree that’s long-lived and also supportive of biodiversity. I don’t think there’s any other tree that offers as great a variety of environmental benefits.

Finally, I would say baobab trees are part of human culture, not just a preoccupation with the African landscape. Everyone knows about the baobab’s extraordinary character. The more I learn about the baobab, the more I realize that people everywhere treat the tree as special.

Prof. Rashford was interviewed by NTBG Bulletin editor Jon Letman. The interview was edited for clarity and length.

NTBG cares for six species of baobab (Adansonia spp.) in three of its five gardens: eight trees in McBryde Garden; one in Kahanu Garden; and six at The Kampong including a robust Adansonia digitata collected by botanist David Fairchild in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania in 1928. That tree (pictured here) was felled by three hurricanes: Cleo (1964), Wilma (2005), and Irma (2017) and now grows horizontally, thriving at The Kampong. Photo by Brian Sidoti