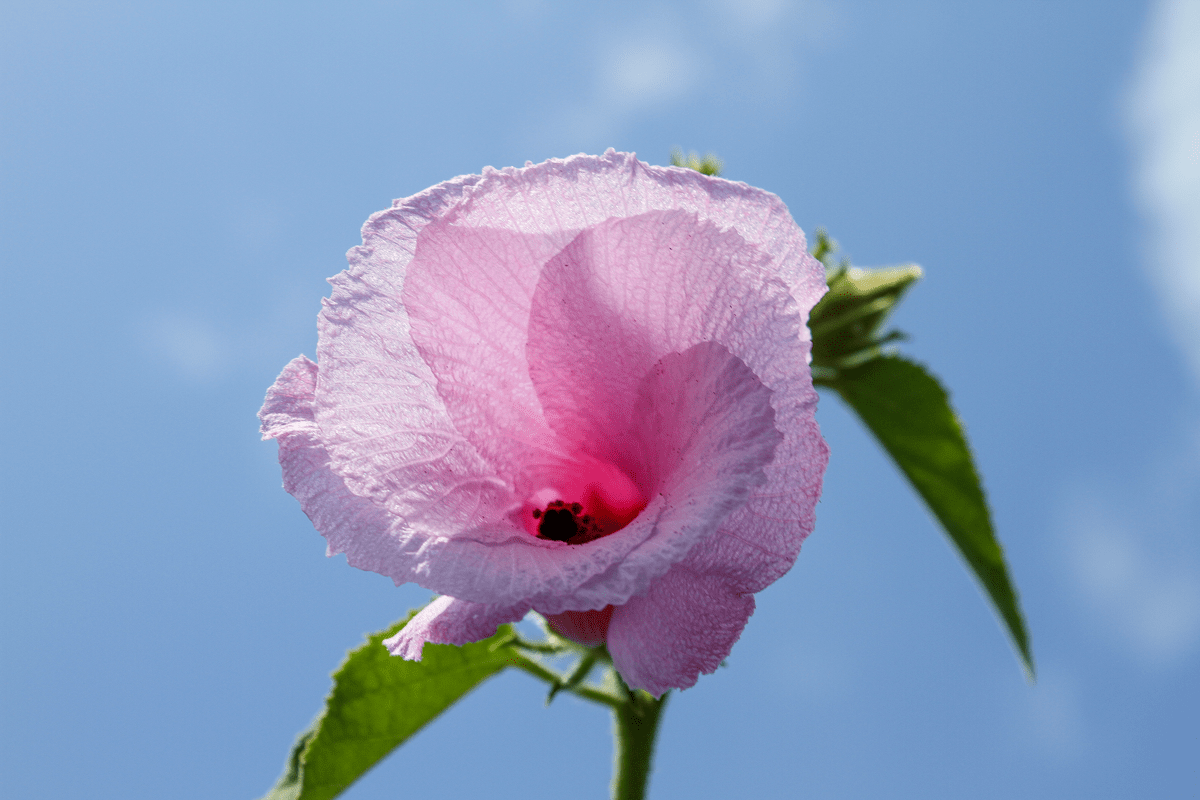

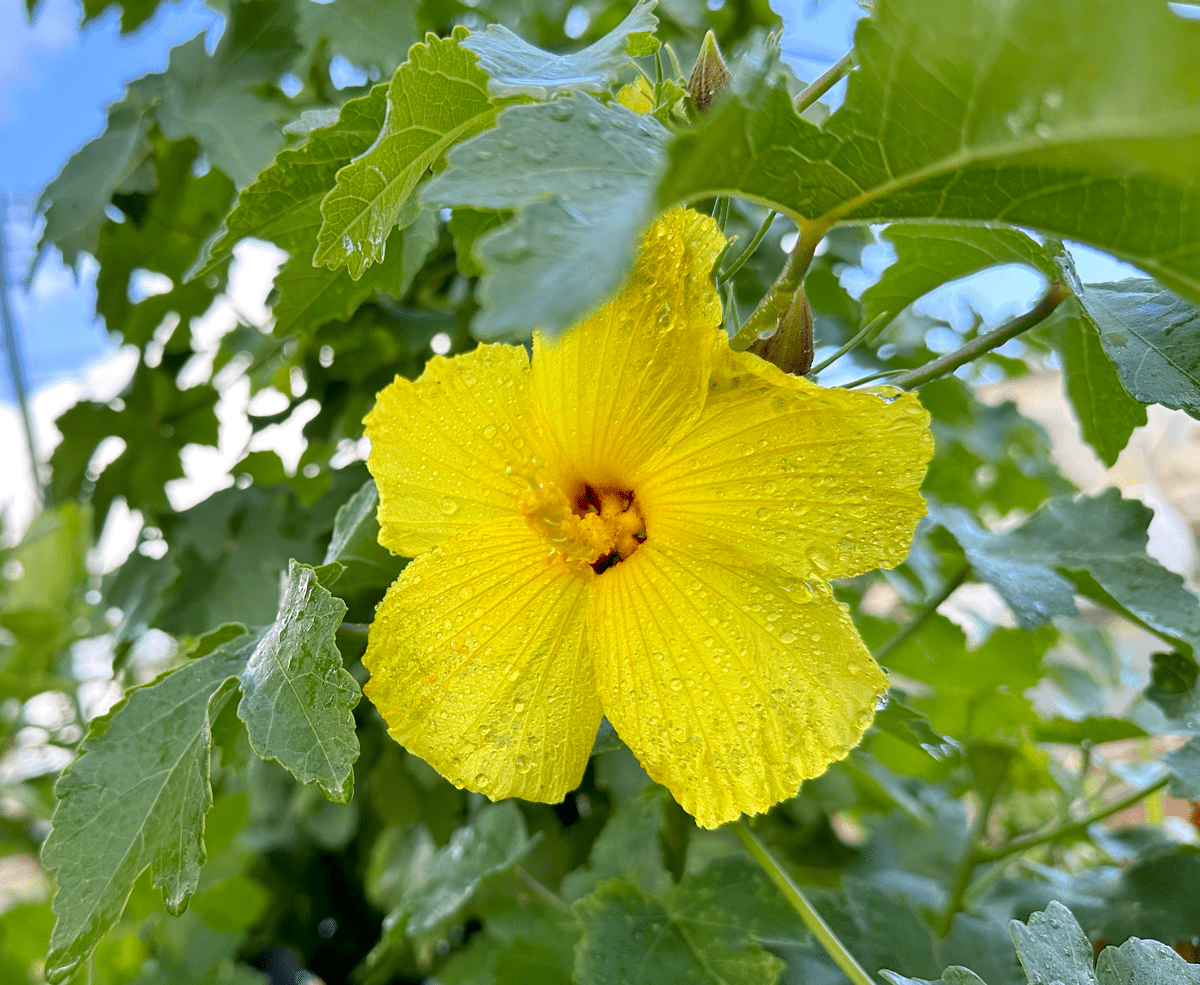

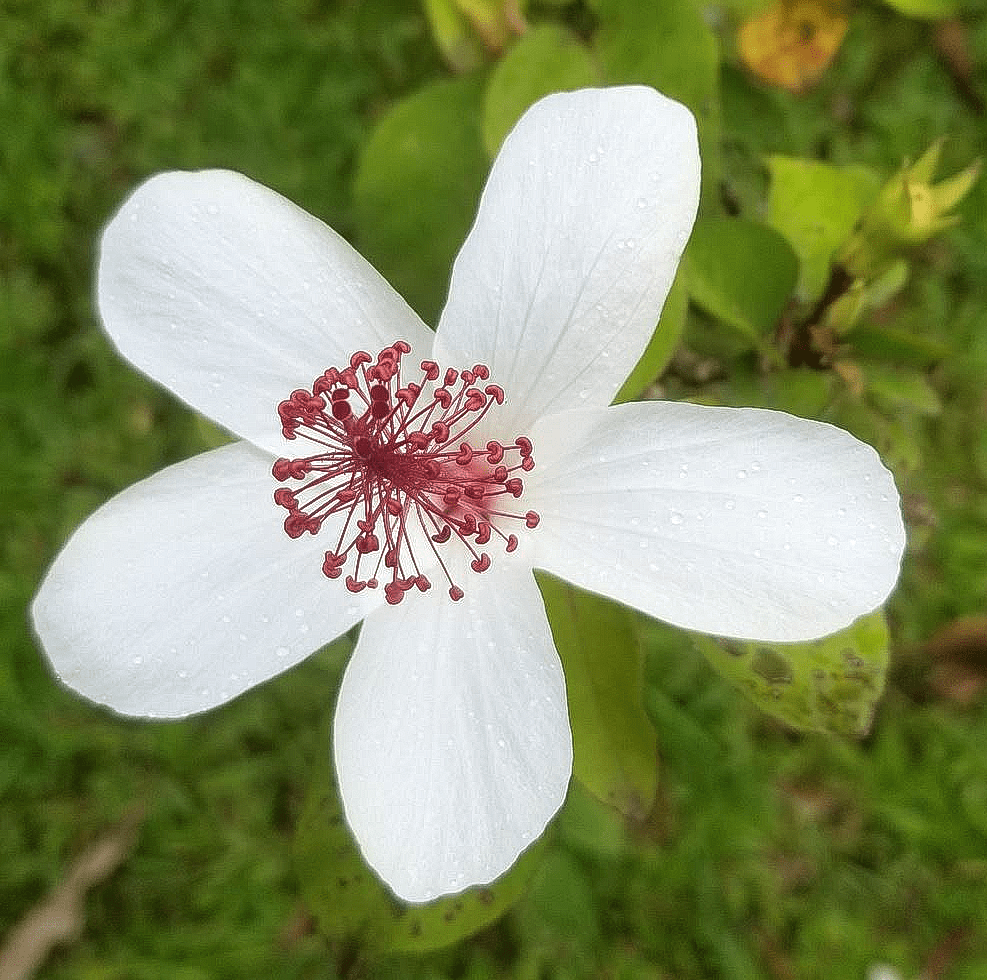

A few of Hawaiʻi’s native hibiscuses. From left: Maʻo hau hele (Hibiscus brackenridgei), kokiʻo keʻokeʻo (Hibiscus arnottianus subsp. immaculatus), kokiʻo ʻula (Hibiscus clayi), and ʻakiohala (Hibiscus furcellatus)

By Kapiʻolani Ching, Communications Coordinator

Featuring Dr. Kawika Winter, Dr. Seana Walsh, and Natalie Blum

Hawaiʻi is home to around six native hibiscus species each with their own unique beauty and story. Flowers range in color from yellow, white, red, orange, and even light purple. Leaves also vary in shape, size, texture, and color. Among Hawaiʻi’s native hibiscuses is maʻo hau hele (Hibiscus brackenridgei), the state flower of Hawaiʻi.

Hear guests Dr. Kawika Winter, Dr. Seana Walsh, and Natalie Blum share their experiences with a few of Hawaiʻi’s native hibiscuses and why our native hibiscuses deserve greater acknowledgement and visibility among the many iconic images that have come to represent Hawaiʻi.

Read more

Maʻo hau hele (Hibiscus brackenridgei)

In Hawaiʻi, hibiscuses are a familiar sight. However, it might come as a surprise to learn that many of the hibiscuses commonly seen in landscaping across Hawaiʻi are ornamental varieties, many of which are hybrids or cultivars that are genetically related to our native species, yet it’s not common to see our true native hibiscuses.

So how did these other ornamental hibiscuses become so closely associated with Hawaiʻi?

This could possibly trace back to 1923 when lawmakers designated hibiscus as the official floral emblem of the Territory of Hawaiʻi, but didn’t specify a species of hibiscus. Considering that Hawaiʻi is home to several native hibiscus species and there are over 200 species of hibiscus worldwide, it’s no surprise that there were different opinions as to which hibiscus truly represents Hawaiʻi. As time passed, many came to believe that the non native Chinese red hibiscus, also known as Hibiscus rosa-sinensis, was Hawaiʻi’s official flower.

In 1988, legislators aimed to clear up any confusion by designating a species to represent Hawaiʻi. They chose the beautiful maʻo hau hele or Hibiscus brackenridgei, Hawaiʻi’s native yellow hibiscus. But despite this, there was and continues to be some slight confusion as to which hibiscus is Hawaiʻi’s official flower.

Dr. Kawika Winter, former director of Limahuli Garden and Preserve and currently a research professor at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, recalls his own childhood and moments of confusion he encountered regarding the state flower.

“When I was in preschool, we were coloring in various coloring sheets. One coloring sheet was the state flower. I remember wondering what color to color in the hibiscus, and I recall being stuck between red and yellow. I can’t remember which one I ended up going with or why I was even torn between those two, but that’s a very early memory for me.”

“At some point later on, I learned that the state flower was yellow and was a native hibiscus. I was really happy about that, but I also realized I had never seen this flower before. I then learned it was super rare. What a poignant story for Hawaiʻi’s state flower to be so rare that most people don’t even know what it looks like in real life.”

We have all these iconic symbols of beauty that have been promoted around the world as a way to attract people to Hawaiʻi–but all that beauty is only skin deep. By learning about our native flowers and in getting to know the deep history that they connect to, that’s the real beauty of Hawaiʻi and my eyes.

“And then full circle, when my son was in school, they had several coloring sheets for various state things, such as the state bird and state flower. For the state flower, the sheet correctly read “yellow hibiscus” at the very top. But the teacher had crossed that out and wrote “red hibiscus.” My son came home and showed this to me and I thought “No, that’s wrong! It’s supposed to be yellow!”

Let’s clear up any confusion. Hawaiʻi’s state flower is maʻo hau hele, Hibiscus brackenridgei, a beautiful, yellow, native hibiscus. But does it really matter if some people confuse our state flower with other hibiscuses?

“The amazing thing about Hawaiian plants is by getting to know them you get to understand a deeper history of Hawaiʻi,” added Dr. Winter. “We have all these iconic symbols of beauty that have been promoted around the world as a way to attract people to Hawaiʻi–but all that beauty is only skin deep. By learning about our native flowers and in getting to know the deep history that they connect to, that’s the real beauty of Hawaiʻi and my eyes.”

Dr. Seana Walsh, conservation scientist and curator of living collections at the National Tropical Botanical Garden, shares her experience studying kokiʻo keʻokeʻo, or Hibiscus waimeae subsp. hannerae.

“I have several really special memories working with kokiʻo keʻokeʻo, Hibiscus waimeae subsp. hannerae, which is endemic to Kauaʻi. One memory was of working with our plants outplanted in Limahuli Garden. In the genus hibiscus there are two to three hundred different species worldwide. We have two different species of white hibiscus in Hawaiʻi and what makes them unique is that they’re very strongly fragrant.”

Some may know and love kokiʻo keʻokeʻo for their beautiful fragrance, but the allure of kokiʻo keʻokeʻo’s flowers also help it to nurture and sustain another critical relationship.

“Because of the nectar composition, the fact that they’re white, and the fact that they’re so fragrant, we suspected that kokiʻo keʻokeʻo (Hibiscus waimeae subsp. hannerae) may be hawk moth pollinated,” said Dr. Walsh. “So we set out at Limahuli to observe pollinators during the day and at night. After sunset, we saw all these non native hawk moths coming to visit the garden plants. That was really exciting! Although they weren’t native hawk moths, just knowing that they are attractive to hawk moths was exciting to observe.”

When it comes to plant conservation, it’s important to understand plant-pollinator relationships. If, for example, an outplanting is planned for a particular plant and we know that plant has a critical relationship with an animal pollinator—in addition to the outplanting, it’s important to also think about how to support habitat for that pollinator.

So how can we determine what animal pollinators may have a special relationship with a certain plant?

“There are some combined floral traits that, we suspect, evolved to be more attractive to certain animal pollinators,” added Dr. Walsh. “Flowers that are typically red, have little to no fragrance, and have sugars rich in hexose sugars tend to be attractive to birds as pollinators. Plants that are white flowered, fragrant, and have nectar rich in sucrose tend to be more attractive to moths.”

“In Hawaiʻi we often think of our native birds as being pollinators. They certainly are, though many have gone extinct. However we suspect that the vast majority of Hawaiian plant species were pollinated by insects. Many of those insects would have been moths, either hawk moths or smaller moths.”

Kokiʻo ʻula (Hibiscus clayi)

Natalie Blum, a master’s student in botany at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa describes what she loves most about kokiʻo ʻula, or Hibiscus clayi, Hawaiʻi’s red hibiscus.

“One thing I really like about Hibiscus clayi is how teeny tiny its flowers are. Some flowers are so small, about the size of a handheld eraser. Others are a little bigger. But in general they’re so delicate and precious. I wish people had more of the native hibiscuses, like Hibiscus clayi, in their mind when they think of hibiscuses in Hawaiʻi.”

Natalie recalls her first experience getting to know kokiʻo ʻula while a student at Kauaʻi Community College (KCC).

“There’s actually a Hibiscus clayi growing at KCC. That was my first time seeing one. I was taking botany classes with Brian Yamamoto, and he had us do some projects with hibiscus. We each had to chose a hibiscus and I chose Hibiscus clayi. There’s one planted right outside the nursing building there on campus. That project was at the very start of my career in botany. I’m happy that it started with Hibiscus clayi and I’m excited that I get to work with it again as part of my master’s project.”

With few plants remaining in their natural habitat, it’s critical to safeguard the genetic diversity of kokiʻo ʻula. Natalie’s research involves strategically pollinating various kokiʻo ʻula– through self-pollination as well as cross-pollination–with the aim of generating seeds. These seeds will then be sown in NTBG’s seed lab and nurtured in our conservation nursery, where Natalie will monitor each plant’s vigor and overall health. The hope is to eventually grow strong and healthy plants that can be outplanted back in their natural habitat.

“I’m working with NTBG and also the Plant Extinction Prevention Program (PEPP). I’m using their ex-situ collections of Hibiscus clayi to do some pollination treatments. I’m doing some selfing, some outcrossing, and also transferring pollen between both locations to see if we could create a new kind of outcross where we’re potentially introducing more genetic diversity that would not have otherwise come about. The overall goal is to make seeds, germinate them and hopefully they grow into nice strong plants that could be outplanted. Hibiscus clayi is critically and federally endangered, so it definitely needs some help in the wild to better its populations.”

Hibiscus furcellatus

Hibiscus brackenridgei

Hibiscus arnottianus

Hibiscus waimeae subsp. hannerae