New Research From NTBG’s Breadfruit Institute

NTBG’s Breadfruit Institute Director Dr. Diane Ragone and co-authors at the University of Hawaii’s College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources (UH-CTAHR) and the University of British Columbia, British Columbia Institute of Technology, and University of Guelph have recently published research papers based on findings using NTBG’s breadfruit conservation collection in Hawaii. The UH-CTHAR paper is entitled Breadfruit and Breadfruit Diseases in Hawaii: History, Identification and Management can be read in its entirety here.

The second paper, South Pacific cultivars of breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis (Parkinson) Fosberg and A. mariannensis Trécul) and their hybrids (A. altilis × A. mariannensis) have unique dietary starch, protein and fiber, appears in the Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. The abstract is available here.

NTBG’s Breadfruit Institute promotes the study, conservation, and use of breadfruit for food and reforestation. Learn more at https://ntbg.org/breadfruit.

The Need is Upon Us

Approximately one million plant and animal species are threatened with extinction worldwide. Now more than ever, the need is upon us to protect plants and unlock solutions to the environmental challenges we face. With your help, NTBG has been meeting the need to save plants and stemming the tide of extinction in tropical regions worldwide for more than 55 years. When you support National Tropical Botanical Garden, you help save plants and people. This story is part two of a three-part series. Follow along to learn more about your impact and NTBG’s plant-saving science, conservation, and research initiatives. Read part I | Read part III

Botanical history is rarely boring. Often full of tall tales, larger-than-life personalities, exploration, and discovery, the establishment of the National Tropical Botanical Garden as we know it today is no exception. With support from some of the biggest names in botany and pressures of the precarious geopolitical landscape of the early to mid-20th century, the need to establish a National Tropical Botanical Garden and home base for the study and conservation of tropical plants located within the United States was critical. Find out how a group of committed citizens, visionary botanists, and philanthropists made it possible and how NTBG continues to address the need to save plants and people in the 21st century.

Fairchild and Rock

Dr. David Fairchild (1869 – 1954) and Dr. Joseph Rock (1884-1962), two internationally famous plant explorers, ‘planted the seed’ that would one day become NTBG. Fairchild, an American botanist and one of the most famous plant explorers in history, created the Section of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction of the United States Department of Agriculture. He spent nearly 40 years traveling the world, searching for plants that would serve the American people. As a result, Fairchild is credited with introducing hundreds of important plants to the United States, including mangos, alfalfa, nectarines, dates, cotton, soybeans, pistachios, and flowering cherries. Today, Fairchild’s personal estate in Coconut Grove, Florida, is home to NTBG’s Kampong Garden.

Right: Dr. Joseph Rock, Austrian-American botanist, explorer, and ethnographer helped develop the first herbarium in Hawaii for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. He collected and documented an enormous number of plants throughout the Hawaiian Islands and became the Territory of Hawaii’s first official botanist. He is the author of numerous scholarly articles and five books about Hawaiian flora.

Joseph Rock emigrated to the United States from Austria in 1905. With a keen interest in botany, he ended up in Honolulu, where he lived for 13 years and became a leading scholar on Hawaiian flora. He helped create the first herbarium in Hawaii for the USDA and published seminal works on Hawaiian flora, including The Indigenous Trees of the Hawaiian Islands. Rock was mentored by and formed a friendship with Fairchild, who instilled the importance of establishing a botanical garden in Hawaii to conserve rare plants and serve as a center for scientific research. From 1920 to 1949, Rock dedicated his time and work to botanical exploration and ethnographic research in China. While abroad, he continued to correspond with other notable botanists, Dr. Harold Lyon, and Dr. Harold St. John, about the need to establish a national garden in Hawaii.

When Rock returned to Hawaii in the 1950s, he noted that many of the Hawaiian species he documented and collected early in his career had disappeared. This species decline and political instability in some tropical regions where most botanical research was conducted meant the need to create a facility to study and protect tropical flora accessible from the United States was more urgent than ever.

The Garden Club of Honolulu

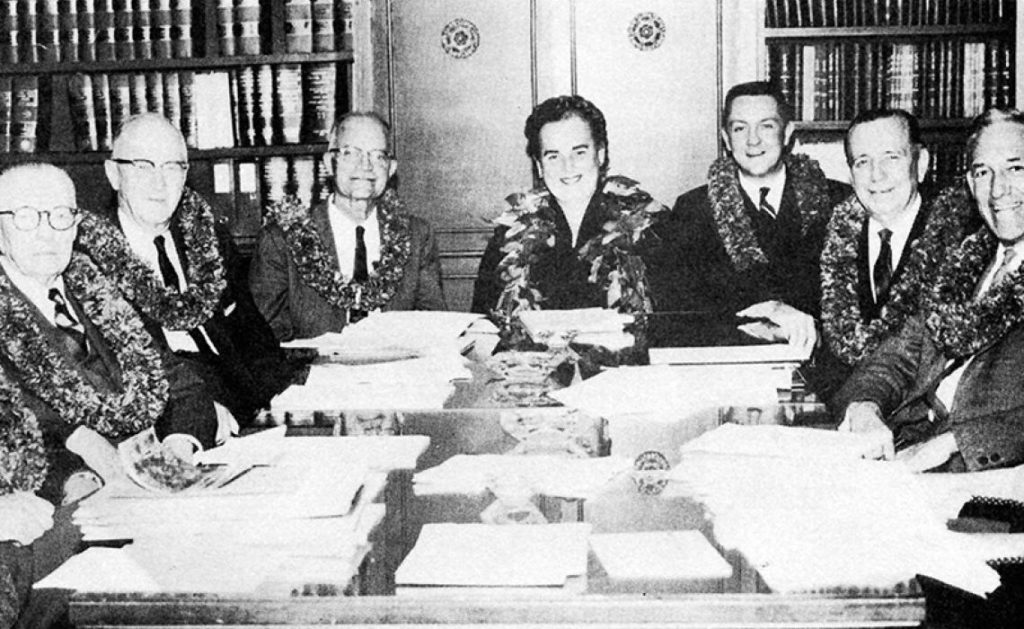

Lyon and St. John wrote prolifically about the need for a national garden in Hawaii and helped bolster much-needed support from the scientific community; however, Rock found his greatest ally in Mrs. Elizabeth Loy McCandless Marks. Mrs. Marks was a leading member of Honolulu society and president of the Garden Club of Honolulu. She championed the idea of creating a national garden and earned the support of community leaders and philanthropists Robert Allerton, Henry Francis duPont, Paul Bigelow Sears, Horace Albright, and Deane Malott. She even garnered the attention of the influential Garden Club of America in Washington D.C. In doing so, Mrs. Marks nationalized the need to create a garden in Hawaii. As a result, she was elected as a founding Trustee of the Hawaiian Botanical Gardens Foundation, which began to build the case for congressional charter in 1959.

“As time passes, we will need to depend more and more on the plants of the tropics and now is the time that information about them should be accumulated rather than waiting until the need is upon us and the information not at hand.”

– Dr. William J. Robbins, Director, New York Botanic Garden (1937 -1958), quoted from the U.S. National Tropical Botanical Garden Proposal

To Charter by Act of Congress

In the spring of 1964, The Hawaiian Botanical Gardens Foundation submitted a proposal to American citizens. In it, they urged, “The need is upon us.” To that point, there was not, nor had there ever been a comprehensive Tropical Botanical Garden established in the United States. American scientists and students relied upon research facilities abroad to conduct tropical botanical studies and understand conservation needs. They argued that there would come a time we would depend upon tropical plants and should accumulate knowledge sooner rather than waiting for the moment of need.

In August of that same year, Congress determined a compelling case had been made and enacted a federal charter that established the private, nonprofit Pacific Tropical Botanical Garden, now known as National Tropical Botanical Garden. Senator Daniel K. Inouye was instrumental in guiding this effort to its successful conclusion. President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Public Law creating and incorporating the institution by charter on August 19, 1964.

Saving Plants, Saving People Today

To this day, NTBG is the only tropical botanical garden with a charter from the United States Congress, five locations, and a more than 55-year history of documenting, studying, and protecting tropical plants. Our network of gardens, preserves, and research centers encompass more than 2,000 acres with locations in Hawaii and Florida. Thousands of species from throughout the tropical world have been gathered, through field expeditions, collaborations with other institutions, and researchers to form an unparalleled living collection.

Our collection includes the largest assemblages of native Hawaiian plant species and breadfruit cultivars in existence. Unfortunately, many of the species in our collections are threatened and endangered, or have disappeared from their native habitats entirely. In our preserves and beyond our garden boundaries, NTBG is working to restore native habitats and save plants facing extinction. Our gardens and preserves are living laboratories and classrooms for staff, scientists, researchers, students, and visitors worldwide.

When you support NTBG with a gift or membership, you support critical conservation and research that saves plants. You become part of a legacy of plant protectors, botanists, and environmental enthusiasts who have made the world a better place for plants and people for generations, and safeguard our future.

Always Upon Us

How Biocultural Conservation Helps us Learn from the Past to Protect Plants Today

Approximately one million plant and animal species are threatened with extinction worldwide. Now more than ever, the need is upon us to protect plants and unlock solutions to the environmental challenges we face. Looking to the past and learning from ancient Hawaiian sustainability practices may reveal the answers we need to safeguard our future. With your help, NTBG is stemming the tide of plant loss in tropical regions worldwide. When you support National Tropical Botanical Garden, you help save plants and people. This story is part one of a three-part series. Follow along to learn more about your impact and NTBG’s plant-saving science, conservation, and research initiatives. Read part II | Read part III

With approximately 1,300 native plant species, 90% endemic to the islands, conserving Hawaii’s flora presents an urgent challenge. Since 2000, 30 Hawaiian plant species have been classified as extinct, bringing the total of Hawaiian flowering plant and fern extinctions to about 130. This and the recent news that officials at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service removed eight bird species and one plant known only to Hawaii from the Endangered Species List due to extinction are sobering reminders that the need to protect plants and restore wild habitats is upon us.

Learning from the Past

Protecting biodiversity is foundational to Hawaiian culture, and scientists and staff at National Tropical Botanical Garden have been dedicated to documenting, studying, and protecting the unique flora of the tropics for more than 50 years. While news of species loss and human impact on our changing climate seems bleak, looking to our past provides hope for the future.

Hawaii is home to the most diverse set of ecological conditions on the planet. Most life forms on Earth could find their preferred habitat within the 27 life zones located within the island chain. Tucked between towering emerald peaks on the north shore of Kauai, the Limahuli Valley is one of the most biodiverse valleys in the Hawaiian Islands. It is home to dozens of endangered plants and birds found nowhere else on Earth and has been a Hawaiian place for at least 1,500 years. Today, Limahuli is one of the last easily accessible valleys with intact archaeological complexes, ancient agriculture and aquaculture infrastructure, native forest, and pristine stream. It’s also home to NTBG’s Limahuli Garden and Preserve, where science and conservation staff work to protect the biodiversity the Hawaiian culture was built upon and model conservation practices founded in cultural values.

Biocultural Conservation

Biocultural Conservation is an approach to conservation that recognizes the inherent relationship between nature and people.

“It builds conservation efforts based on the best available science and grounded in cultural knowledge, values, and practices,” said Sam’ Ohu Gon III, Ph.D., NTBG Trustee, and Senior Scientist & Cultural Advisor, The Nature Conservancy of Hawaii.

“Instead of viewing people as separate from nature, this people-in-nature approach leads to long-term success because it involves the communities connected to the natural resources of concern and builds a broad community of support for conservation,” he continued.

One of the most well-known land management systems implemented by ancient Hawaiians is the ahupuaa system of ridge-to-reef resource management. Today there are few places where this connection between the Hawaiian people and nature is better demonstrated, or systems preserved than the Limahuli Valley.

“The ahupuaa is a social, ecological unit of land designed to meet the material and cultural needs of the human population living within it while minimizing resource conflicts between neighboring human communities,” said Gon.

The ahupuaa approach recognizes the interconnection between the mountains, ocean, and the role that freshwater plays in linking the two and sustaining life. Each ahupuaa followed the natural boundaries of the watershed and provided the resources needed to cultivate food such as fish, shellfish, shrimp, and crops of canoe plants like kalo (taro), ulu (breadfruit), banana, sweet potato, and others introduced to Hawaii by the first wave of Polynesian voyagers. Archeological evidence of at least a dozen kalo loi (agricultural system for farming taro) has been discovered at Limahuli Garden and dated to more than 800 years ago.

“One thing that makes the Limahuli Valley so special is that we have a historical footprint left for us here,” said Lei Wann, Director of Limahuli Garden. “The work we do in the garden and preserves, as well as the curriculum we teach, is inspired by those who came before us,” she continued.

It’s not just the biodiversity or cultural significance of the valley that makes Limahuli so unique, but the potential it has to inform and change the way we practice conservation and resource management in the 21st century and beyond,” she continued.

Applying Ancient Knowledge to Solve Modern Problems

At the height of ancient Hawaiian society, this resource management system could have provided food for a population of up to a million people without external resources. Today, approximately 90% of the food consumed in Hawaii is shipped in from elsewhere, and more than 80% of the world’s hungry live in tropical and subtropical regions of the globe. Breadfruit, a canoe plant, and crop cultivated by people indigenous to Oceania for millennia, is an ancient staple ideally suited to inform and provide for a modern world. NTBG’s Breadfruit Institute combines traditional farming methods, ancient knowledge, and contemporary science at the Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforest (ROBA) demonstration in NTBG’s McBryde Garden.

“Breadfruit has nourished people for thousands of years and affords the opportunity to cultivate an abundance of nutritious and delicious food in ways that help, rather than harm, people and the planet,” says Dr. Diane Ragone, Director of the Breadfruit Institute.

NTBG has been involved in the conservation of breadfruit since 1977, and The Breadfruit Institute was established in 2003 to promote the conservation, study, and use of breadfruit for food and reforestation. NTBG’s unique breadfruit collection represents a global resource to support efforts to advance regenerative agriculture and agroforestry, food security, and economic development.

“We’ve lost some of our understanding of how limited our natural resources really are,” said Mike Opgenorth, Director of NTBG’s Kahanu Garden and home to the most extensive collection of breadfruit varieties and species in the world, preserving some varieties that no longer exist in their native lands. “By looking into our history and utilizing traditional ecological knowledge, we have the opportunity to compare important metrics of well-being and resource availability over time which can inform community-centric approaches to conservation today,” he continued.

Together for Nature

Today 85% of the land once home to diverse ecosystems, and native flora before human contact in Hawaii has been lost to the human footprint. Human activities such as deforestation and land clearing for agricultural purposes contribute to the loss of biodiversity and our changing climate. However, we have the knowledge and ability to change and minimize our impact. Now is the time to look to the past to protect our future and take responsibility for the need that is upon us. Support biocultural conservation efforts at NTBG with a year-end gift today. Together we can make a difference, protect biodiversity, and restore nature. Donate now.

Additional Resources

Are you interested in learning more about biocultural conservation? Check out these resources.

Biocultural Conservation, NTBG

Webinar: Biocultural Stewardship and Restoration, NTBG

A Hawaiian Renaissance That Could Save the World (Gon, Winter)

Biocultural Conservation with Sam ‘Ohu Gon Webinar, The Nature Conservancy, Hawaii and Palmyra

Saving the Kamakahala of Kauai

by Kenneth R. Wood, Research Biologist

Botanists and enthusiasts of the Hawaiian flora may recognize the genus Geniostoma by its older name, Labordia, or by its melodic Hawaiian name kamakahala. The genus includes Geniostoma helleri, a divinely beautiful and Critically Endangered Kauai endemic tree species in the Logania family. Long ago, the seed of the original founder was likely carried to the Hawaiian Islands by a bird. Over millennia, kamakahala evolved in isolation into a lineage of 19 extraordinarily unique taxa, eight of which are federally listed as endangered, each a masterpiece of evolution.

The conservation of kamakahala can be difficult since plants are either male or female and require the presence of both sexes in the colony. Insect visitation of flowers is also needed for pollen exchange. Where there are highly fragmented and separate individuals, biologists need to gather pollen from males and hand-pollinate the isolated female when she is with receptive flowers.

Over the last few decades, NTBG’s Science and Conservation team has mapped all seven species of kamakahala on Kauai, including over 100 Geniostoma helleri individuals throughout Kokee’s mesic forests and Kauai’s western canyons. This phytogeographical (referring to the geographical distribution of plants) knowledge of distribution and abundance has been fundamental in our conservation efforts, and we are thrilled to report that we have exceeded our expectations for the conservation of G. helleri.

In the spring of 2021, collections were made from five separate female trees, with one of those collections rendering over 1,000 seeds, the total number of seeds collected for this project increased to approximately 2,800. These are by far the best collections we’ve ever acquired from Geniostoma helleri. Portions of seed are being cultivated by NTBG’s Horticulture team, and significant numbers are being preserved in our seed storage facility under the curation of seed bank and laboratory manager Dustin Wolkis.

Another single-island endemic kamakahala on Kauai is Geniostoma lorencianum. In the early 1990s, while searching with entomologists in remote interior canyons for the rare endemic fabulous green sphinx moth (Tinostoma smaragditis), NTBG staff discovered a new species of kamakahala which was described and ultimately named in honor of Dr. David Lorence, NTBG’s senior research botanist.

Only a single colony of this kamakahala species has ever been found, which included three males and one female tree. Lorence’s kamakahala is a wonderful example of inter-agency conservation. The collaborative efforts of NTBG, along with the Kauai Plant Extinction Prevention Program (PEPP), and the Hawaii State Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DOFAW) have resulted in successful seed collections of G. lorencianum, followed by nursery propagation, and finally reintroduction back into the forests where the species was originally discovered. Many dozens now occur in their natural habitat and are protected within a fenced exclosure from goats and pigs. DOFAW has made great efforts to maintain that exclosure.

In Kauai’s rugged, wet windward and northern forests, another extremely rare and strikingly beautiful kamakahala occurs. Named in honor of Reverend John Mortimer Lydgate (1854-1922), Geniostoma lydgatei has exquisitely delicate flowers and the smallest fruit capsules of any kamakahala. Geniostoma lydgatei also occurs in the Upper Limahuli Preserve where NTBG biologists are methodically mapping and monitoring individuals and have been collecting seed for conservation.

During the spring and summer of 2021, PEPP and NTBG have made significant observations of Geniostoma lydgatei in lowland wet ohia forest, but this extraordinary species is still only known from several hundred individuals. NTBG plans to maintain and enhance viable populations of this federally endangered species in the fenced Upper Limahuli Preserve.

Currently NTBG’s director of science and conservation, Dr. Nina Ronsted, has partnered on a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant to study the phylogenetic relationships and diversification of the entire Hawaiian lineage of kamakahala. The grant will also include 11 other Hawaiian plant radiations in need of molecular and taxonomic work. This NSF research is in partnership with Washington University, University of California-Los Angeles, UC-Berkeley, Smithsonian Institution, and involves several NTBG staff who will be collecting and organizing leaf material for the proposed gene sequencing.With approximately 1,300 native plant species, 90 percent of them endemic, the challenge to conserve the Hawaiian flora can be overwhelming. It’s sobering to think that around 30 Hawaiian plant species have gone extinct since 2000, raising the number of extinctions to approximately 130 species of flowering plants and ferns.

This fact should leave us with a deeper appreciation of the need for greater focus and funding to secure and build populations of the Hawaiian flora. NTBG secured a grant to conserve Geniostoma helleri from The Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund, but further expansion of horticultural facilities, staff, and increased funding is recommended to successfully manage our endangered plants and forests. Like the concept for the Ark of Noah, we are gathering Hawaii’s rare plants together to be preserved, grown, and planted back into the wild.

Video: Breadfruit Featured on CNN’s ‘Call to Earth’

CNN’s ‘Call to Earth’ series takes you inside NTBG’s Breadfruit Institute to the Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforest (ROBA) to learn how breadfruit is good for people and good for the Earth. Watch how this traditional tropical crop has inspired chefs and farmers and led to global partnerships bringing breadfruit to the world.

Watch here: https://www.cnn.com/videos/world/2021/10/25/breadfruit-hawaii-spc-intl-c2e.cnn

Biggest Plant Conservation Wins of 2021

As we enter the final months of 2021, it’s important to take stock of the progress we have made together in protecting plants and people. Thanks to you, 2021 has been a great year for NTBG and tropical plants! Here are some of the amazing things we have accomplished together.

Growing Green

We’re going off the grid! Across all our gardens, we are improving our energy independence by repairing, upgrading, and installing new photovoltaic systems. Limahuli Garden even installed a water filtration system directly connected to the stream while The Kampong was able to install water bottle refill stations in an effort to reduce waste from single-use plastic. All projects were funded by our Growing Green campaign this spring, so thanks to YOU for making these projects possible.

IUCN World Conservation Congress

Members of our Science and Conservation team contributed to multiple sessions, reaching around 4,000 attendees while building deeper relationships with conservation partners across the globe. NTBG coordinated and hosted a 90-minute Thematic Stream Session during the Congress on the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation (GSPC). This session was moderated by NTBG President Chipper Wichman and included conservation leaders from six different countries. It also featured our own Dustin Wolkis, Seed Bank and Laboratory Manager, who also serves as the Deputy Chair of the IUCN Seed Conservation Specialist Group.

Climate Change Video Series

You helped us reach over 20,000 views of our Kauai Climate Change Series! With support from the County of Kauai, our Science and Conservation team produced five videos that provide a summary view of challenges Hawaii faces from a changing climate. Thanks for watching, sharing, and spreading the word about the challenges we face so we can better work to save plants — and people in the future. View videos.

NTBG Completes IUCN Red Listing for all Kauai Endemic Plants

Assessing endemic species across the Hawaiian Islands helps scientists and conservation managers around the world better evaluate threat risks and aid in the formulation of conservation strategies. Among the eight main Hawaiian Islands, Kauai has the highest level of endemism (species found only in one specific location) and biodiversity. Completing assessments of all Kauai single-island vascular endemic plants brings international attention to the threats they face and increases efforts to save them. Read more.

Historic Fruit Production in Upper Preserve

In the Upper Limahuli Preserve, we are seeing the literal fruits of our nearly 10 years of labor monitoring rodents in the southwest bowl. We had the largest ripe fruit collections from both Pritchardia perlmanii and Clermontia fauriei, both of which are usually decimated by rodent predation.

NTBG Receives High Level Accreditations

This summer, we were thrilled to receive accreditation from Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) as an Advanced Conservation Practitioner carrying out globally significant conservation activities. Our Living Collections team also successfully renewed the highest level IV of accreditation from The ArbNet Arboretum Accreditation Program, which recognizes international industry standards for arboreta. Read more.

Visitor Programs Thrive in Second Half of the Year

This Spring we experienced an increase in travel and garden visitors! The steady stream of traffic allowed us to bring back visitor program staff and increase capacity to welcome folks into our gardens. Whether you were experiencing the gardens for the first time or coming home, thank you so much for your support. Book a tour.

Weekly Aloha Market

Our South Shore Visitor Center took advantage of the beautiful outdoor setting to launch a weekly market. Hundreds of visitors are now able to safely explore the visitor center gardens and shop for locally made gifts, products and produce every week! Read more.

Local Plant Sales

Throughout the year, our gardens have continued to hold local plant sales, distributing over 1,500 plants to community members. A combination of native plants, ulu trees, and other desirable home gardening plants and vegetable starts were propagated and sold.

Brighamia Outplantings

Outside of the new Kahanu Garden Visitor Center, staff constructed a custom planter in an effort to cultivate and strategically hand pollinate the Critically Endangered Brighamia rockii (Alula). This plant was grown in our Conservation Nursery on Kauai before being transported by NTBG staff to Kahanu Garden for outplanting and hand pollinating. This project was funded in part by a grant awarded by the National Geographic Society.

Harvest Donated to Local Food Banks

Many island residents continued to struggle with food insecurity in 2021. An impressive 2 ½ tons of fresh produce were harvested from the Breadfruit Institute’s Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforest and donated to the Kauai Independent Food Bank, Aloha Aina Poi Co., and the Marshallese Church of Waimea. Harvest was also made available distributed to NTBG staff, volunteers, and interns.

Plant Discoveries

Drone technology has greatly increased our ability to discover new plant populations in remote mountain terrain. NTBG drone specialist Ben Nyberg and botanist Ken Wood recently discovered 10 individuals of Kadua fluviatilis and 95 individuals of critically endangered Cyanea asarifolia on windward Kauai. Find out what else we discovered in 2021 by registering for our webinar: Celebrating New Hawaiian Plant Discoveries in 2021.

You make Saving Plants, Saving People possible! Mahalo nui for being a part of our ohana. We can’t wait to see what the rest of 2021 has in store.

Video: Cliff Dwellers of Kauai

NTBG staff and drone footage is featured alongside our partners at Hawaii’s Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) /Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DOFAW) and the Plant Extinction Prevention (PEP) program in this 28-minute DLNR-produced video “Cliff Dwellers of Kauai…and the people who hang with them!”

Cliff Dwellers of Kauai…and the people who hang with them! from Hawaii DLNR on Vimeo.

Article: Preserving Hawaii’s Biodiversity Is Up To Us

The recent delisting of 23 native species in our islands is just the tip of the iceberg.

When the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced plans to delist 23 species from the endangered species list due to their presumed extinction, it highlighted the importance of preserving biodiversity and supporting conservation.

Read more at: https://www.civilbeat.org/2021/10/preserving-hawaiis-biodiversity-is-up-to-us/

NTBG Receives Advanced Conservation Practitioner Accreditation From Botanic Gardens Conservation International

This month, NTBG received accreditation from Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) as an Advanced Conservation Practitioner carrying out globally significant conservation activities.

“At a time when our daily news feeds are filled with darkness, it is a delight to share this bright spot for NTBG,” said Janet Mayfield, NTBG CEO and Director. “We are so proud to receive this recognition for our work saving some of the world’s rarest plants and join a select global group of only 15 botanical gardens to date,” she continued.

The BGCI Advanced Conservation Practitioner Accreditation is the highest level of accreditation obtainable and recognizes excellence and international leadership in plant conservation policy, practice, and education. In addition to the application, and a conservation collections assessment carried out by BGCI and an anonymous external peer review, NTBG had to provide documented evidence of:

- Compliance with international conventions

- Collections of conservation value

- Training in conservation-related disciplines offered

- Native plant species horticultural trials

- Participation in international scientific research

- Conservation activities, including In situ conservation

- Sustainability practices

- Substantial staff specialist skills

- International network membership

The collections assessment confirmed that National Tropical Botanical Garden holds 3,538 taxa in its overall collection, with 3,445 taxa in the living collection and 842 taxa in the seed bank. From the overall collection 683 taxa are unique in ex situ collections worldwide (636 unique in the living collection and 47 unique in the seed bank), and 1,765 taxa that are present in five or fewer ex situ collections globally (1,677 in the living collections and 618 in the seed bank).

Further, NTBG’s collection includes 628 taxa that are globally threatened according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (595 in the living collection and 324 in the seed bank). Of these 628 taxa, 44 taxa are uniquely conserved at the National Tropical Botanical Garden (27 in the living collection and 17 in the seed bank) and 359 taxa are held in five or fewer ex situ collections worldwide (327 in the living collection and 268 in the seed bank).

Lastly, the percentage of threatened taxa in the collections of The National Tropical Botanical Garden is above average when compared with other accredited gardens. Of the 1,215 taxa that are threatened at some level (nationally, regionally or globally) according to assessments stored in the BGCI database, 67 taxa are uniquely conserved at the National Tropical Botanical Garden (41 in the living collection and 26 in the seed bank) and 574 taxa are held in five or fewer ex situ collections worldwide (523 in the living collection and 410 in the seed bank).

“This recognition really highlights the excellent curatorial standards of our living collections, the value of our collections and the importance of conservation work carried out by botanical institutions like NTBG,” said Nina Rønsted, NTBG Director of Science and Conservation

You can learn more about plant science and conservation from National Tropical Botanical Garden in a variety of ways. Review our science and conservation web pages or join us for a garden tour at one of our locations on Kauai, Maui, or in Miami, FL.

NTBG also holds the highest level IV of accreditation from The ArbNet Arboretum Accreditation Program, which recognizes international industry standards for arboreta

Four Crowd Pleasing Botanical Cocktails to Try at Home

Want to impress your guests or treat yourself to something special? Check out these four botanically-inspired cocktails that are surprisingly simple to customize with a little advanced preparation. Let your local farmers market or even your own backyard be your inspiration. These botanical cocktail recipes are versatile so grab what’s fresh and get mixin’!

We let our Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforestry (ROBA) project in McBryde Garden on Kauai inspire the ingredients for these botanical treats. More than 100 plant species and varieties are thriving in this demonstration garden which produces a year-round, environmentally sustainable harvest. Learn more about how NTBG’s Breadfruit Institute addresses critical global food security issues.

These recipes were crafted by the mixologist at Kōloa Rum Company, a local, single batch craft distiller and bottler of premium Hawaiian rums. Kōloa Rum has supported NTBG and plant conservation since 2013. Learn more about corporate sponsorship.

Walk in the Garden

This light and refreshing, turmeric inspired cocktail will transport you and your guests to the sunniest of gardens. Make the Sunny Shot and honey syrup in advance for an easy mix on the day. Don’t have access to fresh turmeric root? You can substitute with powdered turmeric.

¾ oz Sunny shot

1 ½ oz Honey Syrup (equal parts water and honey)

1 Kaffir Lime leaf

2 oz Kōloa Coconut Rum

Garnish: Lemon and bee pollen

Splash with 1 ½ Club Soda

Instructions: Shake Kōloa Coconut Rum, Sunny Shot*, kaffir lime leaf, and honey syrup with ice then strain into chilled glass. Top with club soda. Garnish with a lemon wheel and bee pollen

*Sunny Shot: Combine and strain ¾ cup Ginger Juice, ¾ cup Olena (turmeric) Juice, 3 cups Lemon Juice

Tropical Refresher

Looking for something super simple? Then this breezy tropical refresher is for you. Fresh or canned guava juice can be used and fresh herbs like kaffir lime leaf or basil make it special.

2 oz Guava

1.5 oz Kōloa Coconut Rum

2 Kaffir Lime Leaf

Lemon/lime Soda

Garnish: Meyer lemon Wedge

Instructions: In a shaker tin, combine Kōloa Coconut Rum, guava juice, and kaffir leaves then muddle about 5 times. Pour into glass, add ice and splash with lemon lime soda. Garnish with a lemon wedge.

Gardenia Treasures

This floral masterpiece will truly wow your guests, and the gardenia lemonade is surprisingly easy to compile. If you’re not sure where to find gardenias, other edible flowers like jasmine (pikake), hibiscus and lavender are all excellent substitutions. Kōloa White Rum complements vanilla, spicy green notes as well as rich creamy scents.

3oz Gardenia Lemonade*

1 ½ oz Kōloa White Rum

Garnish: White petals

Instructions: Stir ingredients in a mixing glass and strain in a chilled coupe glass.

*Gardenia Lemonade: Equal Parts lemon juice, gardenia simple syrup** and water.

**Gardenia Syrup: soak 5-10 gardenias in a pint of simple syrup for 10 hours then remove flowers.

Lychee Dream Shifter

This amazing color-shifting cocktail occurs naturally from the Bluebell Vine flower (Clitoria ternatea). The flowers are commonly used as a natural, vibrant blue food coloring but changes to a lovely purple when citrus is added. The dreamy colors are a beautiful surprise that will wow your guests. We added fresh juiced lychee, a fan favorite here on Kauai.

2 oz Kōloa Coconut Rum

1 oz Bluebell Simple Syrup*

1 oz Fresh Lychee Juice strained

Squeeze Lemon Juice (Approx. 1 oz)

Garnish: Bluebell Vine Flower

Instructions: Build in shaker. Shake all ingredients with ice and strain into martini glass. After enjoying the beautiful blue color, squeeze lemon juice and stir, watch the color shift to a mysterious purple.

*Bluebell Simple Syrup: 2 cups sugar to 2 cups distilled water and 5 Blue Bell Flowers. Bring water to a boil, add sugar and flowers, stir until sugar is dissolved. Remove from heat and leave flowers in steeping until the desired color is reached.

.svg)