NTBG Environmental Journalism Program Accepting applications for 2023

NTBG Environmental Journalism Program

Offered on Kauai May 1-5, 2023

The Hawaii-based National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG) is accepting applications for its Environmental Journalism Program (May 1– 5, 2023) designed for professional journalists (employed as staff or freelance) working in broadcast, print, online, and new media. The immersive five-day program provides a background in tropical botany, ecology, and biocultural conservation, a progressive approach that honors Indigenous legacies, integrates cultural values and centers our communities to advance meaningful, long-lasting conservation impacts. The EJ Program is structured to enhance well-informed, accurate reporting on environmental issues with a focus on tropical and island systems and the importance of plants and biocultural diversity.

The Environmental Journalism (EJ) Program is offered at NTBG headquarters, in three of its five botanical garden sites, and other locations on the island of Kauai. Established in 1964 by a Congressional Charter, NTBG encompasses ancient Hawaiian cultural and archaeological sites, extensive botanical living collections, a LEED-certified botanical research center, a botanical library and rare book collection, a seed bank and laboratory, a historical garden estate, a horticulture and conservation center, and other natural and man-made resources and facilities.

NTBG provides richly varied indoor and outdoor living classroom settings in which to study and experience new and traditional ideas while exploring critical concepts of biology, ethnobotany, biocultural conservation, habitat restoration, seed banking, agroforestry, and herbaria specializing in tropical and sub-tropical flora.

EJ Program presenters include NTBG staff and non-staff scientists, educators, and experts in botany, horticulture, taxonomy, field biology, ornithology, ethnobotany, and other related fields.

Participating journalists can expect to gain a greater understanding of important elements and current developments that will assist them in reporting on science and the environment. The goal of NTBG’s EJ Program is to introduce critical information and concepts in order to foster a greater understanding of these issues. The EJ Program is not expressly intended to provide source material for prospective news stories, although NTBG staff and other speakers may be available for interviews outside program hours.

NTBG provides all participants free on-site shared housing, airport transfer, and ground transportation. EJ Program participants are responsible for the cost of their own airfare to Lihue Airport on Kauai, meals, incidentals, and any additional expenses such as U.S. visas, etc.

Apply starting: Wednesday, February 1, 2023 (6 a.m. U.S. Eastern Standard Time)

Deadline to apply: Tuesday, February 21, 2023 (by 5:00 p.m. U.S. Eastern Standard Time)

Notice of acceptance: Wednesday, March 8, 2023

Dates of program: Monday, May 1 – Friday, May 5, 2023

*All participants must arrive on Kauai by Sun. April 30 and depart NTBG housing by Sat. May 6th

Required to Apply: Complete Environmental Journalism Program online application and provide two samples of recent work in print, audio, video, or online reporting (URL links only please). Submission of a CV/resume is optional.

APPLY AT: https://ntbg.wufoo.com/forms/environmental-journalism-program/

Website: https://ntbg.org/education/professional

Email: education@ntbg.org

NTBG President Charles R. “Chipper” Wichman Retires

Concluding a nearly half-century career with the National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG), Charles R. “Chipper” Wichman, the organization’s president and former chief executive officer, is retiring at the end of 2022. Wichman began his association with the Garden in 1976 as an intern at the suggestion of his grandmother Juliet Rice Wichman.

Over the course of five decades, Wichman has served NTBG as a groundsman, foreman, horticulturalist, garden director, director, CEO, and president. NTBG was established in 1964 with a congressional charter as the Pacific Tropical Botanical Garden. In 1988, after the acquisition of botanist David Fairchild’s Miami property The Kampong, the organization was renamed by an act of Congress as the National Tropical Botanical Garden.

Comprised of five gardens and five preserves in Hawaii and Florida — Allerton Garden, McBryde Garden and Lawai Preserve, and Limahuli Garden and Preserve on Kauai; Kahanu Garden and Preserve on Maui; the Awini and Kaupulehu preserves on Hawaii Island; and The Kampong in Miami — NTBG spans 2,000 acres and curates living collections that include more than 100,000 accessions.

NTBG also includes the Breadfruit Institute which conserves the world’s most extensive collection of breadfruit varieties on Maui and Kauai, operates the LEED Gold Juliet Rice Wichman Botanical Research Center at NTBG headquarters, and the International Center for Tropical Botany at The Kampong.

Under Wichman, NTBG has become a recognized global leader in discovery, scientific research, conservation and education focused on rare and endangered plant species. NTBG perpetuates the survival of plants, ecosystems, and cultural knowledge of tropical regions, advancing the field of biocultural conservation.

“Not many people are given the chance to have a career that truly makes a difference in the world. I am grateful for this opportunity and immensely proud of my role in NTBG’s evolution and growth.”

Chipper Wichman

During his tenure, Wichman, in partnership with his wife Hauoli Wichman, established the 1,000-acre Limahuli Valley Special Subzone on Kauai’s north shore, enabling NTBG to undertake true “ridge to reef” conservation utilizing traditional Hawaiian knowledge and values. This unique property was left to the Wichman’s by Chipper’s grandmother which they in turn gifted to NTBG in 1994.

In 1997, the Wichmans took on the management of Kahanu Garden in Hana, Maui where they helped coordinate and oversee the restoration of the Piilanihale Heiau, one of the largest archaeological and cultural structures in the Pacific. He was also part of a collaborative process to develop the Hawaii Strategy for Plant Conservation modeled after the Global Strategy for Plant Conservation.

In 2015, Wichman helped establish the Lawai Kai Special Subzone on Kauai’s south shore. Additionally, in 2016, Wichman served as vice-chair on the national host committee that successfully bid for the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s World Conservation Congress. The event welcomed more than 10,000 delegates from 192 countries to Hawaii for the first IUCN congress ever held in the United States.

“Not many people are given the chance to have a career that truly makes a difference in the world,” Wichman said. “I am grateful for this opportunity and immensely proud of my role in NTBG’s evolution and growth.”

Among his many honors, Wichman received The Garden Club of Honolulu’s Hui Mala Award (2015), the Award of Merit from the American Public Garden Association (2016), the Medal of Honor from The Garden Club of America (2018), the American Horticultural Society’s Professional Award (2020), and was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Science degree from Florida International University in 2020. He also served as director when the Limahuli Garden and Preserve was named “Best Natural Botanical Garden” by the American Horticultural Society (1997).

Wichman expressed his appreciation for NTBG’s Board of Trustees, staff, and supporters. He also thanked his wife Hauoli Wichman who worked alongside him as his partner and advisor, contributing her professional skills, deep cultural knowledge, and Hawaiian heritage as they jointly built a personal and professional legacy, advancing the cause of rare plant discovery and biocultural conservation throughout Hawaii, across the Pacific, and beyond.

Wichman continues to serve on the Hawaii Conservation Alliance Bio-security Subcommittee, the Rapid Ohia Death Task Force, Laukahi Hawaii Plant Conservation Network, Hui Makaainana o Makana, and other community bodies.

After dedicating nearly half a century to the National Tropical Botanical Garden, the Wichmans said they look forward to enjoying more time with their family, working closely with the community, and spending time relaxing in the gardens and amongst the plants that they have dedicated their lives to protecting.

NTBG now operates under the leadership of Janet Mayfield who was appointed CEO and director in 2019.

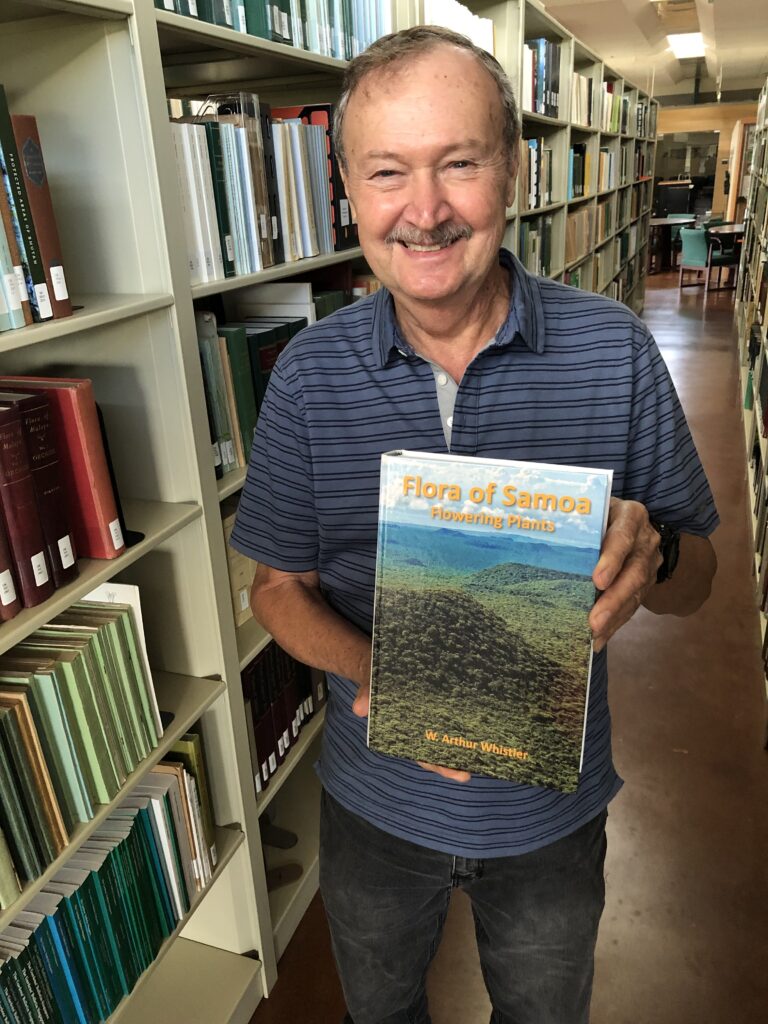

Flora of Samoa Available for Purchase

The newly published Flora of Samoa is now available for purchase

The National Tropical Botanical Garden is pleased to announce that the print edition of W. Arthur Whistler’s Flora of Samoa: Flowering Plants is now available for purchase. Decades in the making, the 940-page book includes 159 color figures, presenting the rich and diverse flora in its known entirety.

The Flora of Samoa project was spearheaded by Hawaii-based ethnobotanist W. Arthur Whistler who worked closely with Samoan partners to explore, collect, and study the Samoan flora, allowing him to incorporate a considerable number of taxonomic treatments emphasizing Samoa’s traditional ethnobotanical knowledge.

Whistler dedicated his career to documenting the Samoan flora. In 2015, NTBG commissioned Whistler as a McBryde Fellow to prepare a written flora of Samoa for publication. After Whistler’s death in 2020, botanists at NTBG and the Smithsonian Institution worked together to complete final editing and updating of the manuscript to ensure the flora was published.

Based on Whistler’s 4,900 specimen herbarium collections, the flora is the most current and complete scientific assessment of the Samoan archipelago’s 543 native plant taxa, including 177 endemic species, 290 naturalized flowering plant species, and 225 ferns and fern allies. More than one-third of Samoa’s native plants are found nowhere else on earth. Samoa’s largest family of flowering plants is the orchid family (Orchidaceae), with 101 native species, followed second by the coffee family (Rubiaceae), with 47 native and six naturalized species.

Flora of Samoa: Flowering Plants is listed at $100 (USD) plus 4% general excise tax and shipping. The book can be ordered by emailing NTBG staff at lorence@ntbg.org or kmagoun@ntbg.org.

Plant Conservation Wins of 2022

Thanks to our staff, partners, and community of supporters, NTBG celebrated many wins for tropical plants this year. With each discovery, initiative, and innovation, we are growing a brighter future for generations of plants and people. We’re excited to share these conservation highlights with you.

Plant Conservation Wins of 2022

The Mamba collecting ʻakoko (Euphrobia eleanoriae) in Limahuli Valley. Thanks to our partners at Outreach Robotics and the University of Sherbrooke for the amazing footage.

Introducing the Mamba

In addition to discovering endangered plants, our drone program is now able to safely collect them. The Mamba, a tool developed by Outreach Robotics and University of Sherbrooke researchers with the support of NTBG scientists, has collected 12 endangered species on Kauaʻi so far. Their progress was published in the journal Nature – Scientific Reports, documenting how the new technology is redefining plant conservation on cliffs and other extreme habitats. Check out the latest press coverage on the Mamba drone arm from Reuters and Scientific American.

Fresh Lysimachia iniki cutting being processed in NTBG’s Conservation Nursery

Hope takes root for Kauaʻi’s rare plants

This summer, our Conservation Nursery celebrated as three different critically endangered plants collected by the Mamba set roots – laukahi (Plantago princeps var. anomala), ʻakoko (Euphorbia eleanoriae), and Lysimachia iniki.

While NTBG has previously attempted to propagate cuttings of L. iniki and ʻakoko, it was the first known attempt to do so with laukahi. The successful rooting of all three species is an inspiring accomplishment for the Mamba field collection and nursery teams, providing further proof that new technology can advance rare plant conservation. Read the full story from the Conservation Nursery team.

Pteris hillebrandii

Rare Hawaiian fern spores propagated from herbarium vouchers

Our Fern Lab has made exciting progress in the cultivation of rare Hawaiian ferns this year. Spores were collected from herbarium vouchers (pressed plants that are preserved and stored for research). While plants are dried, pressed, and stored in the herbarium vouchering process, the hope was that rare fern spores might still be able to germinate under the right conditions. The experiment was a success! Some spores collected off the herbarium sheets dated back to 1985. Staff hope to continue to see growth and have mature plants soon. Advances like this would not have been possible without supporters like you! Your fundraising directly contributed to the hiring of a full-time Fern Lab Technician, Emily Sezate.

Seana Walsh, Conservation Biologist, inspecting ʻālula (Brighamia insignis) in NTBG’s Conservation Nursery

Over 400 ʻālula outplanted on Kauaʻi

As part of a collaborative project with Botanic Gardens Conservation International and Chicago Botanic Garden, hundreds of ʻālula (Brighamia insignis) were planted at McBryde Garden and Limahuli Garden this year. For the last two years, NTBG and Chicago Botanic Garden have been conducting crosses and monitoring seed viability and plant growth for a National Geographic Society-funded project titled “Saving the remaining genetic diversity of species that are extinct in the wild: resurrecting Brighamia insignis.” This ex situ collection was set up to monitor the survival and growth of plants with different levels of genetic diversity, which will help inform how we move forward with in situ restorations of plants like ʻālula. As with animals, plants are healthier when bred in diverse gene pools. To expand the scope of this approach, NTBG is partnering with Chicago Botanic Garden on a new grant. Conservation biologist Seana Walsh will focus on building genetically diverse collections of Critically Endangered Hawaiian endemic species kokiʻo ula (Hibiscus clayi) and hōlei (Ochrosia kauaiensis). Walder Foundation is funding this project.

Hāhā (Cyanea kuhihewa) discovery

Saving the rarest of the rare

First discovered by NTBG botanists in 1991, a Kauaʻi species of hāhā (Cyanea kuhihewa) was nearly lost in the aftermath of Hurricane ʻIniki. Not only did ʻIniki destroy portions of the native forests in Limahuli Valley where the plant was discovered, it was followed by an influx of invasive species. The last known Cyanea kuhihewa died in 2003 as a result of these pressures but was rediscovered in 2017 in a nearby valley. NTBG botanists collected over 7,000 seeds from the mother tree in this small population before it died earlier this year.

In 2022, NTBG partnered with Lyon Arboretum to propagate a batch of Cyanea kuhihewa trees. Combined with efforts at our own Conservation Nursery on Kauaʻi, 60 trees were propagated and twelve outplanted. The remaining trees are ready to go out later this year. To put an exclamation point on this exciting news, a team of botanists from NTBG, The Nature Conservancy and the Plant Extinction Prevention Program discovered a new wild population in July of 2022 increasing the number of known wild individuals to four. This focused work and collaboration with conservation partners is bringing the species back from the brink of extinction.

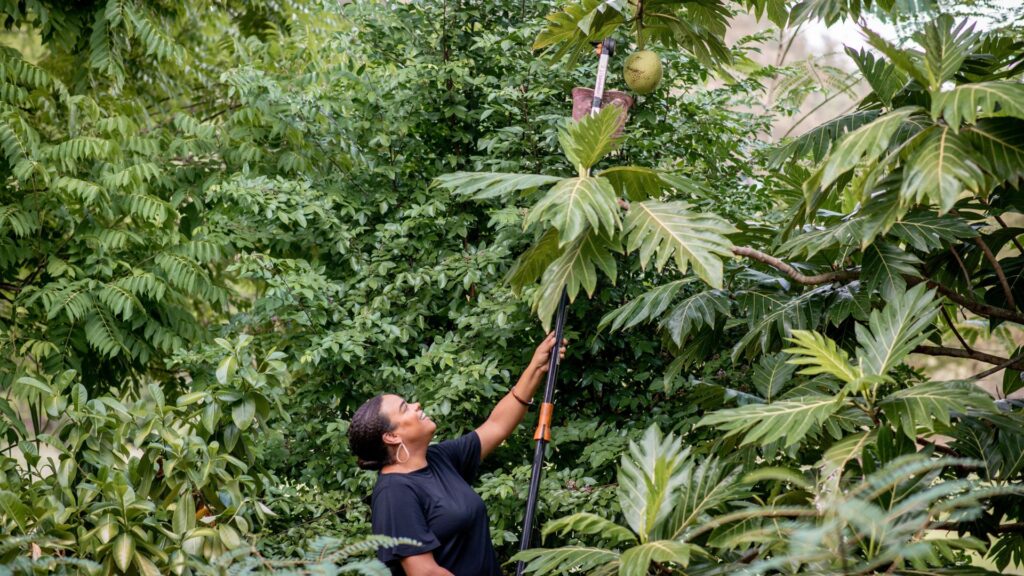

Breadfruit Institute Coordinator, Noel Dickinson, harvesting breadfruit

ROBA celebrates five years

The Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforestry project (ROBA) was established in 2017 at our McBryde Garden on Kauaʻi. On Kauaʻi, over 90% of our food is imported from off-island, leaving the island vulnerable to food shortages. ROBA was started as a way to address food insecurity both locally and throughout the tropics through research on best practices and education.

With an increase in diversity of cultivated plants throughout ROBA’s five years, staff has seen a decrease in weeds. Less time is spent weeding and mowing has decreased from two to three times per week at the start of the project to just once or twice a month. As a result, more time can be dedicated to research, crop harvest, and education. Over 17 tons of produce has been donated to Kauaʻi nonprofits that serve communities island wide and we continue to share what we learn with community members, students, and volunteers.

A legendary banana takes root at Kahanu Garden

During an expedition into Waihoʻi valley, the Kahanu team visited a shrinking banana patch thought to be planted by Kahuʻoi, a legendary Hawaiian farmer of ancient times. The variety, suspected to be ʻIholena Kapuaʻ is now back at Kahanu Garden, joining our banana collection. We are excited to preserve and better understand varieties like this that are part of moʻolelo kahiko (old stories) and thought to have helped people of East Maui during a time of famine.

Cracking the code at NTBG’s Seed Bank and Laboratory

Our seed bank safeguards rare and endangered Hawaiian plants for conservation. As part of this process, it’s vital to learn how to germinate seeds. That task can be challenging depending on the species. Koholāpehu (Dubautia latifolia), a member of Hawaiʻi’s famous Silversword Alliance with a uniquely vining habit, is one such plant. Collaborating with associate researcher Bruce Baldwin, our team was able to use a new technique to successfully germinate koholāpehu for the first time. Several plants are now growing in our Conservation Nursery!

Leafless vanilla orchid (Vanilla barbellata)

Community Conservation for the Everglade’s rare orchids

Due to lost habitat and poaching, Florida’s native orchids are disappearing at an alarming pace. As part of our Orchid Initiative at The Kampong, we brought several rare species into cultivation at the garden and led outreach efforts to inspire the public to grow them. In conjunction with the University of Miami, we produced an instructional video and online resources that share how to grow endangered orchids from the Everglades in the home environment.

Watch our 2022 Science & Conservation Highlights webinar

These highlights are only made possible through plant people like you.

Help us grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants through a donation today.

The Root Cause of Happiness

People need plants. They are the root cause of our health, habitat, and happiness. More than ever, plants need you. Join us this fall as we explore how cultivating deeper connections with plants can grow a brighter tomorrow for our ecosystems and communities.

Lei Wann, Director of Limahuli Garden & Preserve, happy amongst the kalo (taro)

Think of your happy place—a location or memory that you recall fondly—and I bet plants are in the picture. Maybe they define the surroundings of a cherished moment. Maybe they’re on the plates of a meal shared with loved ones. Maybe plants are your happy place: a beloved tree, garden, or landscape that fills you with joy. The root cause of happiness, it turns out, is often plants.

Hawaiian lei are the epitome of plant joy. A master lei maker is a matchmaker. With devotion, the lei maker weaves together the right plants for the right person. Some lei, like those crafted with hundreds of ʻilima or kou blossoms, are a labor of love. As the soon-to-be-recipient of the lei dreams in the quiet dawn, hundreds of petals are gathered. As the recipient begins to wake, hands begin to weave the lei together, each blossom strung with utmost care. As the recipient’s day progresses hour by hour, the lei grows flower by flower. At just the right moment, the lei maker and the recipient come together. The gift that is given is a pure expression of aloha. The lei encircles them in a love that only the lei maker, and the specific harmony of woven plants, can provide. It is hard to imagine a smile bigger, a smile warmer than when one receives a lei.

(L) Fern Lab Technician Emily Sezate presents a fern lei. (R) Limahuli’s Department Administrator & Volunteer Coordinator Angelina Kissida strings a plumeria lei

Plants make us happy, everywhere. Remarkably, it seems that plants help us express our most human emotions. Gifts of flowers, like lei, are a timeless way to communicate our deepest feelings. Indeed, plants guide many of our cultural and spiritual practices. Hula, a revered dance described by King David Kalākaua as the “heartbeat of the Hawaiian people,” is inextricably rooted to the plants of Hawaii. Plants can be both muse and material. In addition to representing plants in virtually every media, artists throughout time have drawn, painted, woven, sculpted, carved, and dyed with plants. Without plants, the world would be lifeless in many definitions of the word. Across tropical regions and throughout the world, plants make life happier.

Lei Wann begins weaving a kī (ti) leaf lei

Ties that bind

Watching Lei Wann, Director of Limahuli Garden & Preserve, make lei is as mesmerizing as the beautiful plants she uses. Her hands know each flower, frond, fruit, and seed on a profound level. “For me, many plants have deeper connections to my heritage and culture. Being with them or working with them is like being with an ancestor. It’s like being with family.”

Her lei braids together generations of people and plants. Woven into every lei is a heritage of the artform itself as well as the moʻolelo (stories) behind each plant. Like the cord that holds the lei together, an inseparable connection to the ‘āina (land) threads everything together. Her intimate knowledge of plants, and their inherent meanings, guides her process as she makes lei for friends new and old.

“For me, plants have deeper connections to my heritage and culture. Being with them or working with them is like being with an ancestor. It’s like being with family.”

Lei Wann, Director of Limahuli Garden & Preserve

Lei loves to teach traditional plant practices like lei making. “By teaching these plant practices, I am keeping my culture and traditions alive. When you engage in plant practices, you are making deep connections with plants. You are interacting with them and getting to know them on a deeper level.” Nurturing community connection to the ‘āina is a key part of Limahuli’s approach for restoration. Lei leads the stewardship of Limahuli Valley and Preserve with an ahupuaʻa frame of mind: that ecosystem restoration is fundamentally tied to community restoration.

Two of Lei’s favorite plants are laua’e o Makana and pāpala. “For generations, these plants were used to reference our place and people. Laua’e can also be a metaphorical way of speaking of the sweet and cherished people of Haena. Pāpala is part of the famous art of ʻōahi (fire throwing ceremony) of which my ancestors were famous. Pāpala can also metaphorically speak of love and aloha.” Revitalizing plants revitalizes culture. Laua’e and pāpala, among many other invaluable plants, are grown at Limahuli to ensure that ancestral traditions continue.

As family members, as gift givers, as culture keepers, plants make Lei happy. “They bring life and goodness into the world, and for that I am humbled and happy to be in their presence.”

Volunteer Leslie Ridpath tending to endangered plants in the Conservation Nursery

Growing happiness

For NTBG volunteer Leslie Ridpath, gardening is a wellspring of joy and restoration. “I find that my garden gives me a creative outlet. I really enjoy using the color and structure of the plants in a variety of combinations creating different distinct areas. Unlike a painting, there is constant change in a garden.”

When Leslie relocated to Kauai, she began volunteering at NTBG to “learn about the plants that do well in this environment to help me in designing my own garden.” By volunteering across departments, she drew connections between cultivating plants and making a positive impact for our local environment. “I love to learn new things and as I have volunteered in various roles at NTBG, it has really helped to get the bigger picture of what they are trying to accomplish in their mission. By volunteering at NTBG, I’ve had the chance to work with endangered plants, including a study that looks at the impacts of climate change on coastal plants. I find this very rewarding.”

Plants provide Leslie with the inspiration and opportunity to make a difference in her community. By growing plants native to your region, you can too! Native plants provide a refuge for wildlife, are environmentally friendly, and celebrate the beauty unique to your home. For Leslie, growing plants in her garden and as a volunteer at NTBG provides a perennial source of happiness.

(L) Lei Wann gathers a kī (ti) leaf to make lei. (R) The hale (house) nestled in Limahuli Valley

Spreading the love

So much happiness is rooted in plants. They nourish our bodies and feed our souls. They tie generations together, keeping culture alive. Plants also help us share the love. By growing plants, we can cultivate a better world for our families, communities, and ecosystems. What could bring more joy than that?

People need plants. Plants need you.

Plants nourish our ecosystems and communities in countless ways. When we care for plants, they continue caring for us. This giving season, help grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants.

Tropical Plant Coloring Books

Free Downloadable Tropical Plant Coloring Books

Learn more about tropical food plants, Hawaiian culture, and our islands’ unique ecosystems with our new coloring books! Click the images below to download a printable PDF. Each coloring book features beautiful drawings of tropical plants coupled with fun facts, sure to please plant lovers of any age.

About the National Tropical Botanical Garden

Did you enjoy these coloring books? Consider supporting tropical plants through a donation today.

Hope for Habitat

People need plants. They are the root cause of our health, habitat, and happiness. More than ever, plants need you. Join us this fall as we explore how cultivating deeper connections with plants can grow a brighter tomorrow for our ecosystems and communities.

Our homes and habitats are made possible by healthy plant communities

Where are you at this moment? Whether you’re surrounded by wildlife or citylife, you’re in a habitat that is alive with relationships. Species and soil, climate and community, wind and water are working together to make life possible. A Hawaiian proverb reads I ola ‘oe, i ola mākou nei. “My life is dependent on yours, your life is dependent on mine.” Everything in your habitat is intimately connected.

(L) Uma Nagendra admires an ohia lehua. (R) A rock islet in Palau photographed on a recent expedition by Ken Wood

In many ways, plants are the threads that weave this tapestry together. They stitch together entire food webs and provide a patchwork of so many other necessities, down to the very air we breathe. However, in a rapidly changing world, plants and plant communities are disappearing. Each plant lost is a thread cut from this vibrant tapestry, an end to a network of relationships and a potentially reshaped habitat. To restore habitats, it’s vital to rethread them with their unique plants that are a support system for the life they sustain.

Uma Nagendra inspects the beautiful flowers of kokio keokeo (Hibiscus waimeae subsp. hannerae)

Plants are a habitat’s best friend

At this moment, there is a good chance that Uma Nagendra is in the habitats of Limahuli Garden & Preserve. As the Conservation Operations Manager there, she works to understand and restore Hawaiian ecosystems in the face of constant change. Limahuli on Kauai is considered one of the most biodiverse valleys in Hawaii. To perpetuate the environmental integrity of this invaluable place, Uma relies on plants. “Plants are the foundation of nearly every ecosystem – they don’t just enhance the ecosystem, they create it!” shares Uma. “Here in Hawaii, ohia and other montane trees capture mist from the clouds and gather raindrops, forming the cloud forest that feeds all the rest of Hawaiian streams. Their nectar feeds the forest birds; their bark houses mosses, insects, and snails; their roots shelter seabird burrows.”

Limahuli Garden and Preserve totals over 1,000 acres and are managed within an ahupuaa framework, continuing a living legacy of indigenous stewardship. Ahupuaa are Hawaiian land divisions that extend from mauka (mountain) to makai (ocean). Within this framework, humanity and nature are inseparable. The same water that condenses atop the highest ohia in the ahupuaa makes its way through misty falls and mesic forests, through loi kalo (taro terraces) and rushing streams out into a bustling reef. At every section of the ahupuaa, plants sustain life for the ecosystem and community alike.

On a daily basis, Uma experiences the biodiversity that plants make possible in Limahuli’s preserves: Tiny land snails sneaking by on haha (Cyanea spp.) leaves, pueo owls in courtship, Tetragnatha spiders in “full arachnid-yoga poses,” apapane birds diving across the ohia canopy, the barking sounds of ao (Newell’s shearwater), hundreds of opae kuahiwi (mountain shrimp) darting in the stream. All of these precious residents of Limahuli depend on the ahupuaa’s native plants. Without them, Limahuli wouldn’t be the same. “A forest in Hawaii dominated by invasive guava will feel completely different from a diverse ohia forest,” says Uma. “In the ohia forest, you’ll see a wider variety of textures and layers, you’ll feel the moisture hanging in the air, you’ll feel the spongy moss cover beneath your feet, perhaps you’ll even hear more birds and other animals enjoying the trees. Because plants are the foundation for everything else, it truly matters which plants are the ones building that foundation.”

“We can all do our part to make sure our habitats have the support system they need.”

Uma Nagendra, Conservation Operations Manager

Uma and her team work to safeguard and restore the habitats of Limahuli. You can help be the support system for the habitat you call home. “We can all do our part to make sure our habitats have the support system they need by limiting the impact of existing invasive plants, animals, and microbes; avoiding introducing new ones when we enter wild places; and not exacerbating climate change.” Find out what invasive species are impacting your habitat and what native plants share your home. Building awareness and knowledge about the plants that define your habitat is a great step towards caring for the special place you live.

To help us root more deeply into the habitats that support us, Uma recommends a recurring meditation. “Find a quiet moment where you can observe your outdoor surroundings. It doesn’t matter if you’re in an urban environment, rural, suburban, or wilderness – all of these are ecosystems. Try for 15 seconds of stillness, then observe with as many senses as you can. Do you hear or see any animals or plants? What textures, air currents, warmth, or precipitation is present? Repeat the exercise weekly. Can you notice when the seasons begin to change? What animals and plants are active or migrating at different times of the year? Does the air feel different to you as the months roll on?”

Seana Walsh admires alula (Brighamia insignis) flowers at NTBG’s Conservation Nursery

Hope for plants means hope for habitat

Seana Walsh, NTBG’s Conservation Biologist, has been growing a brighter tomorrow for the beloved alula (Brighamia insignis) for over seven years. While extinct in the wild, these charismatic plants that once adorned sea cliffs on Kauai and Niihau have made their way across the world in botanical garden collections and as indoor houseplants. Seana is leading a cutting-edge study to strategically breed these cultivated alula to enhance diversity and plant health. While this strategy has been used in zoos for decades, this major undertaking is one of the first of its kind for plants. Seana’s work with alula is perpetuating a beloved plant for Hawaii. At the same time, she is helping to develop and inform strategies for perpetuating plants—and the habitats they sustain— across the world.

(L) Alula (Brighamia insignis) in bloom. (R) A Molokai alula (Brighamia rockii) at home on a sea cliff

For Seana, bringing plants back from the edge of extinction is a moral obligation. She grew up on the leeward side of Maui, where invasive species and degraded landscapes provided a stark comparison to the native plants and habitats she now nurtures. “Knowing what I know now, and what I experience during my time and work in the forest, it is very clear how different a healthy, native forest both looks and feels compared to one dominated by non-native species,” Seana says. “In a healthy native forest, you won’t see large areas of bare soil or pooling water. Non-native forests with exposed earth cause runoff when it rains and pools of water which are breeding grounds for mosquitoes, a huge threat to our native forest birds. A native forest results in less runoff which equates to more groundwater recharge and less sediments flowing downstream and covering our reefs.”

Kampong by Christina Pettersson

Plants make home, home

Healthy habitats and communities rely on plants. By tuning in to the habitats we call home and the plants that define them, we can learn how to be a support system for the places we love.

People need plants. Plants need you.

Plants nourish our ecosystems and communities in countless ways. When we care for plants, they continue caring for us. Help us grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants.

Five Ways to Give on Giving Tuesday

Everyone can have an impact on #GivingTuesday! Join NTBG on November 29 by pledging your time, skills, voice, or dollars to grow a brighter tomorrow for the tropical plants that sustain and nourish us all. Add Giving Tuesday to your calendar and be sure to follow us on social media!

Five Ways to Give on GivingTuesday

Give money

Donate to NTBG, purchase, renew or gift a membership.

Interested in making a difference year-round? For as little as $10 a month, your monthly pledge helps provide NTBG a steady stream of support no matter how uncertain the times may be. Thank you for considering this helpful option.

Give Your Voice

Speak up! Talk to your friends and family about saving plants.

Need some tidbits to share with the people in your life? If you don’t already, follow us on social to keep up with the latest! Check out our news page for updates on our work and subscribe to our newsletter to stay in the know.

Give Your Time

Volunteer or donate your skills to NTBG.

Interested in becoming a volunteer? Click the button below to explore opportunities.

Give Goods

Buy an item from the NTBG wishlist.

Purchase an item from our wish list and your donation will go directly to meet immediate program needs.

Inspire Others

Organize a fundraiser or share your story online.

Share why you support NTBG with the world! Need a place to start? Download this #unselfie template and tell your story on November 29, 2022.

Even More Ways to Give

Global biodiversity is in crisis. Today we are at risk of losing plants faster than we can discover them. Your partnership and steadfast support help us continue our science, conservation, and research efforts in Hawaii, Florida, and around the world.

Ulu Cheese Casserole Recipe

This holiday season, celebrate the tastes of the tropics wherever you are with breadfruit! Here we feature chef Nikki Gold’s incredible ulu cheese casserole recipe, the dish that scored 1st place at our annual Ulu Cook-off on Maui. We also share preparation tips, additional recipes, and resources for finding breadfruit near you.

“Ulu is such a wonderful and special fruit that when I cook with it, I feel like I am honoring a part of Hawaiian culture. I mean, it is such a beautifully versatile fruit how could I not love cooking with it?

My inspiration for the ulu casserole this year came from my daughter. She loves a particular movie about a rodent chef who makes a casserole that melts the heart of a critic. Like the little rodent, my daughter loves helping me in the kitchen. This casserole was inspired by her using all of her favorite flavors in our kitchen. Ulu, Okinawan sweet potatoes, carrots, and cheese.“

Nikki Gold, chef and 1st place winner of the 2022 Ulu Cook-off

Share your completed dishes with us on social media and tag us @ntbg on Instagram.

Ulu Cheese Casserole Recipe

Ingredients

- 2 – 4 cups breadfruit, peeled and sliced thin

- Two medium Okinawan sweet potatoes, peeled and sliced thin

- One extra thick carrot, peeled and sliced thin

- ½ cup kula (sweet) onion, chopped

- ¼ teaspoon cracked pepper

- ½ teaspoon dried rosemary

- ½ teaspoon dried thyme

- ¾ teaspoon garlic powder

- 1 teaspoon Hawaiian salt

- 1 ½ teaspoon dried parsley

- 5 ounces grated gruyere cheese or sharp cheddar

- ½ cup half-and-half

- ½ cup chicken broth

Cooking Instructions

Step 1

Heat oven to 375℉. Brush the inside of a 10 inch cast-iron skillet with olive oil.

Step 2

In a large bowl, combine ulu, potato, carrots, onion, herbs, salt, pepper, and 90% of the cheese. Mix until everything is evenly coated.

Step 3

Layer thin sliced vegetables upright in the skillet until full. Sprinkle it with remaining cheese. Pour milk and broth over vegetables and cover with tinfoil to seal edges.

Step 4

Bake for 50 minutes and remove foil, continue baking for 15-20 minutes until breadfruit is tender and slightly browned.

Share your completed dishes with us on social media! Be sure to tag @ntbg on Instagram.

Breadfruit History

Polynesians brought breadfruit to the Hawaiian Islands because of the many uses for these important trees. Breadfruit trees continue to provide food, medicine, clothing material, construction materials, and animal feed.

Breadfruit is an excellent dietary staple and compares favorably with other starchy staple crops commonly eaten in the tropics, such as kalo (taro), plantain, cassava, sweet potato, and white rice.

Complex carbohydrates are the main source of energy with low levels of protein and fat and a moderate glycemic index. It is also gluten free. 100g fresh fruit provides 102 calories. Breadfruit is a good source of dietary fiber, iron, potassium, calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium with small amounts of thiamin, riboflavin, and niacin.

The trees are traditionally used and are a major component in mixed cropping agroforestry systems. Breadfruit creates a lush overstory that shelters a myriad of useful plants including yams, kava, noni, bananas, and sweet potatoes.

One of the highlights of the McBryde Garden is NTBG’s Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforestry (ROBA) project which acts as a living classroom and 2-acre demonstration project. The data that is collected by our ROBA team is used to advise local farmers on best practices and techniques. This year, our team was able to ground proof ROBA’s productivity and display breadfruit agroforestry’s ability to support community resilience in times of need. So far, over 6,000 lbs. of breadfruit has been donated to local food banks on Kauai!

Additional Breadfruit Resources and Recipes

Community Supported Agriculture

Wondering how to sign up for a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) subscription or where you can buy breadfruit in Hawaii? Check out the links below to find a source near you.

Find Breadfruit Near You

Hawaii Ulu Co-op Breadfruit Locator: https://eatbreadfruit.com/pages/findbreadfruit

Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) and Farm Locator: https://gofarmhawaii.org/find-your-farmer/

USA Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) Locators

Becoming Plant Passionate

People need plants. They are the root cause of our health, habitat, and happiness. More than ever, plants need you. Join us this fall as we explore how cultivating deeper connections with plants can grow a brighter tomorrow for our ecosystems and communities.

If you haven’t thought about plants today, you’re certainly not alone. Even though plants make our everyday possible, many of us seldom pause to appreciate just how important they are to our health and overall wellbeing. Plants and people go together. In the Hawaiian worldview, kalo (taro) is an older sibling who continues to feed and nourish communities across the islands. Ola ke kalo, ola ke kānaka; ola ke kānaka, ola ke kalo is a Hawaiian proverb that means if kalo lives, Hawaiians live; if Hawaiians live, kalo lives.

(L) Breadfruit being gathered at the Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforest. (R) Noah Kaaumoana-Texeira gathering kalo (taro)

“In some Native languages, the term for plants translates to ‘those who take care of us,’” says Potawatomi botanist and Braiding Sweetgrass author, Robin Wall Kimmerer. From lowering stress and anxiety, to producing cancer-fighting compounds and healthy regenerative agriculture systems, plants are often our best teacher and most helpful remedy. Increasing our awareness and recognition of plants is the first step in protecting our precious biodiversity. Our future depends on it.

Lahela Chandler Correa, Visitor Program Manager at Limahuli Garden & Preserve

Becoming Plant Passionate

Plants feed, shelter, heal, and fuel us. They inspire art, help us express emotion, and guide many of our cultural and spiritual practices. Data also shows that spending time in nature improves our mental and physical health. So, why do we often overlook their importance to all life on Earth and limit our interest in plant conservation?

Researchers have noted a growing indifference to plants. There are many reasons for plant unawareness. In urban areas, many people lack equitable access to plants, parks, and natural spaces. Plants are underrepresented in education. From kindergarten to college, plant science is fading from curriculum and school programs. It also has to do with what’s inside our heads: since most plant life is similar in color, mostly stationary, and densely packed, our brains can be hardwired to lump them together instead of noting their differences. In other words, many of us tend to see the forest and not the trees. Importantly, awareness for plants differs across cultures. Most research on the topic has been done in Western societies, whereas Indigenous communities often have a deep and fundamental awareness of plants.

We must increase our awareness and empathy for the plant life surrounding and supporting us. In his 1968 speech to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, Senegalese conservationist Baba Dioum said, “In the end, we will conserve only what we love; we will love only what we understand and we will understand only what we are taught.” The more we engage with plants and experience their positive effects on our health and wellbeing, the more likely we are to protect them. It’s time to become plant passionate.

(L) Dr. Nina Ronsted examines an herbarium voucher of Madagascar periwinkle. (R) Close-up of Madagascar periwinkle

Modern Medicine and the Power of Plants

Plants have always healed us and today are found in a quarter of our medicines. Yet, most drug researchers focus on synthetically-derived medicines. Despite technological progress, the number of new drugs brought to the market is in decline. However, drug discovery from plants and other natural products continues to be highly productive and effective.

“Today, we are still challenged by a long list of unmet medical needs for safe and effective medicines,” said Nina Ronsted, NTBG’s Director of Science and Conservation. “One of the grand challenges for humankind remains the identification of new leads for pharmaceutical research,” she continued. The need for new leads is just one reason plant science and conservation are essential not only to the health of our planet but also to our people. “It is not easy to guess which plants might cure which diseases,” said Nina. “As extinction accelerates, we risk losing potential medicines even before they are discovered,” she concluded.

Director of Science and Conservation, Dr. Nina Ronsted, admires Madagascar periwinkle flowers

In recent history, compounds from the Madagascar periwinkle have increased the survival rate of childhood leukemia from 10% to 90%. In addition, a compound initially found in Pacific Yew trees (Taxus brevifolia), is the cancer-fighting component of Taxol. This drug inhibits the rapid multiplication of cancer cells. Today, Taxol is on the World Health Organization’s list of Essential Medicines and is one of the most effective drugs for treating multiple forms of cancer.

“The potentially useful compounds that plants have developed over time in response to herbivores overcoming their effects are increasingly complex and specialized,” noted Nina. “Many of these compounds may affect humans and become cures for diseases,” she finished.

With time, plant research and conservation will reveal more about the connection between plant compounds and human health. But what can we do today to strengthen our connection and improve our health right now? The answer is a walk in the park (or garden!).

Noel Dickinson, Breadfruit Institute Coordinator, holding breadfruit in the Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforest (ROBA)

Healthy Plants, Healthy Planet

On any given weekday, you’ll find Noel Dickinson of NTBG’s Breadfruit Institute tending to the trees and edible understory plants in the Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforestry (ROBA) demonstration in NTBG’s McBryde Garden. Breadfruit has long been an important staple crop and a primary component of traditional agroforestry systems in Oceania. In addition to providing food and goods, breadfruit agroforests offer broad ecosystem benefits such as soil and water conservation and biodiversity maintenance essential to long-term island habitation. ROBA is a two-acre display garden and model for implementing breadfruit agroforestry in tropical regions and areas of food scarcity worldwide.

For Noel, breadfruit agroforestry does more than produce nutritious food and regenerate land degraded by erosion, compaction, and loss of organic matter. It nurtures her, builds relationships, and provides an opportunity to learn and grow. “Plants are a huge part of my life, personally and professionally, and breadfruit has had a big impact on me,” said Noel. “Through my work with the Breadfruit Institute at NTBG, I have been able to learn new things as well as literally share the fruits of my labor with my community,” she effused. “I have also, at times, been given a platform to represent the gardens,” she said. “Being an ambassador for not only breadfruit but also NTBG is a great joy for me.”

Studies show it’s not just Noel benefitting from time spent with plants. Plants can generate happiness, reduce stress, and increase positive energy in the home. In addition, access to parks and outdoor spaces increases rates of physical activity and overall healthiness. Research also shows that people who spend more time around plants have better relationships with the people around them.

(L) A ripening breadfruit amongst colorful ti leaves in the Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforest. (R) Noel Dickinson, Breadfruit Institute Coordinator, gathering breadfruit in ROBA

Healthy Today, Here for the Future

Plants and people are inextricably linked. From everyday wellbeing to the next medical breakthrough, we need plants to maintain our health and the health of our planet today. As we navigate and study the effects of climate change, our future also depends on our ability to recognize the plant life surrounding us, learn from it and investigate solutions for what lies ahead.

People need plants. Plants need you.

Plants nourish our ecosystems and communities in countless ways. When we care for plants, they continue caring for us. Help us grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants.

.svg)