Alula Featured in Applications in Plant Science

NTBG’s latest alula research was recently published by Applications in Plant Sciences

For nearly six decades, the National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG) has been saving plants. Among the many rare and endangered plant species NTBG is known for conserving is the genus Brighamia, a member of the bellflower family (Campanulaceae), endemic to (found only in) Hawaii. Called alula in Hawaiian, both species — Brighamia insignis and Brighamia rockii — grow on Hawaii’s steep slopes and high sea cliffs. In the 1990s, National Geographic famously photographed two NTBG botanists rappelling over Kauai’s Na Pali coast, collecting plant material to propagate in the nursery.

In the decades since, Brighamia rockii has dwindled to just eleven known plants that cling to the cliffs of Molokai. Its close relative, Brighamia insignis, last seen on Kauai, is now believed to be extinct in the wild. However, thanks to the efforts of NTBG and others, the alula has been successfully cultivated and is even commercially available as a houseplant in Europe and elsewhere. NTBG staff and scientists continue to conserve and study the alula with ongoing research featured in the most recent issue of Applications in Plant Sciences, a publication of the Botanical Society of America.

In an article co-lead authored by NTBG conservation biologist Seana Walsh, scientists show how the adaptation of pedigrees used by the zoo community can be used to manage botanical garden collections and reduce inbreeding, resulting in healthier plants. Researchers selected Brighamia insignis as their case study. Their findings illustrate the importance of maintaining diversity through strategic cross pollinations.

In the same issue, seedbank and laboratory manager Dustin Wolkis lead authored an article about seed dormancy and germination of Brighamia rockii. The authors found that a high percentage of the seeds germinate over a range of temperatures and are suitable for propagating from seed for conservation. Research suggests these seeds are unlikely to form a long-live soil seed bank and will need human intervention to be reintroduced into the wild.

By continuing to study and conserve this charismatic native Hawaiian plant genus, collaborating with likeminded organizations and institutions, NTBG is playing a leading role in advancing the understanding of rare and endangered plants and ensuring the preservation of irreplaceable biodiversity.

Hope Takes Root for Kauai’s Rare Plants

Advancements in drone technology aid in rescuing rare cliff-dwelling plants

The summer of 2022 started off with hopeful celebration at our Conservation Nursery on Kauai as three different critically endangered plant taxa collected by the Mamba drone arm set roots from cuttings – laukahi (Plantago princeps var. anomala), akoko (Euphorbia eleanoriae), and Lysimachia iniki.

The Mamba, developed by Outreach Robotics with the help of NTBG scientists, is able to collect rare plants from otherwise inaccessible places. Mamba also allows for a much faster retrieval time. What used to take hours of hiking and rappelling to collect plant material, now takes minutes with the Mamba. This result is fresher plant material arriving at our Conservation Nursery and an increase in the likelihood of successful propagation.

Think of it like rescuing an imperiled person from a remote spot. If you hike to reach the person and carry them to safety on a stretcher, the chance that they are under additional stress is much higher than quickly airlifting them. The sooner we can get the patient (plant) back to the emergency room (our Conservation Nursery), the greater chance of survival.

While attempting to set roots from cuttings in both Lysimachia iniki and akoko has occurred before, it was the first known attempt to do so with laukahi due to its rarity. That all three sprouted roots is an inspiring accomplishment for the Mamba field collection and nursery teams, providing further proof of how new technology can advance rare plant conservation.

Laukahi (Plantago princeps var. anomala)

Laukahi (Plantago princeps var. anomala) is a small erect or ascending woody shrub that grows on steep slopes and cliffs in wet forests in the Upper Hanapepe and Kalalau valleys on the Hawaiian island of Kauai. Curiously, laukahi is one of more than 250 species in the genus Plantago, largely temperate in distribution, but also occurring at high altitudes in tropical areas and on oceanic islands like Hawaii. While some consider Plantago species like Plantago major to be invasive or ‘weedy,’ Kauai’s Plantago princeps is Critically Endangered with less than 50 individuals known to occur in the wild.

Further field collection trips with Mamba could have a big impact on the future of critically endangered plants like laukahi. The original cutting is doing well at the nursery and even recently developed a flower stem. A flower means seeds, and seeds mean increased hope for future restoration in the plant’s natural habitat.

Lysimachia iniki

Past samples of Lysimachia iniki brought to the Conservation Nursery were fragments of plants that had fallen from the sheer cliffs below Kauai’s summit after storms. Incidentally, this is how the species got its name. Lysimachia iniki‘s discovery occurred after Hurricane Iniki’s devastating winds dislodged the native plant from its steep habitat. No past plant fragments brought back to our nursery had ever survived. That is until now.

Two Lysimachia iniki propagules are thriving under the care of our staff in the Conservation Nursery. There is only one known population of Lysimachia iniki, underlining the importance of this major breakthrough in the conservation of this Critically Endangered Kauai endemic plant.

Additional Success for Rare Plants

The Mamba has brought additional success beyond laukahi and Lysimachia iniki. A rare Rubiaceae, Kadua st-johnii, grew from a seed collected off of a cutting and a less rare Lysimachia hillebrandii also took root. Lysimachia, a member of the Primrose family, is often difficult to grow from cuttings. The successful rooting of Lysimachia hillebrandii in our Conservation Nursery reinforces that the speed with which Mamba retrieves plant material directly affects survivorship in the nursery.

There have been some setbacks. Akoko (Euphorbia eleanoriae) survived for four months after setting roots. While this specimen did not make it to maturity, it is the first time the species set roots in cultivation. The team at the Conservation Nursery plans to build on the knowledge gained from the first attempt to try again with future field collections.

Ultimately, the Mamba allows us to reach rare plants that are otherwise unreachable. For some of these cliff-dwelling species or any plants that grow in hard to reach areas, these developments in drone technology may be the best hope for their continued survival. “The use of drones also allows a fast turnaround for processing cuttings and placing them in our mist-house or in a temperature controlled location for protection,” says NTBG Nursery Manager, Rhian Campbell. “As we continue to develop protocols for the handling of these cuttings and learn everything we can about propagating these extremely rare species, we are also likely to become more successful with them over time.”

Nothing Beyond Reach

Cutting edge drone technology leaves nothing beyond reach.

By Ben Nyberg, GIS and Drone Program Coordinator

NTBG members who have been supporting our work for years know that the discovery, collection, and conservation of rare plants is central to our mission. Roughly 90 percent of the Hawaiian flora is found nowhere else on Earth, and so saving these plants is a great responsibility. But on an island like Kauai, where many rare plants grow in steep terrain and sheer cliffs, they can be impossible to access on foot.

For decades, NTBG has used traditional rappelling techniques to reach endangered cliff-dwelling plants like alula (Brighamia rockii) but in some cases, the plants are inaccessible to even the most experienced rappellers. In 2016, NTBG began experimenting with drone technology to discover plants that were otherwise beyond our reach.

Soon after our drone program began, we were encouraged by a number of rare plant discoveries in remote, previously unexplored cliff habitat. Drone technology was an exciting new tool that revealed rare plant populations we never imagined we could explore, but even as we made progress, we asked, “what’s next?”

The answer came when we were approached by a group of Canadian researchers from the University of Sherbrooke in Quebec who were grappling with similar challenges. The researchers had started a company, Outreach Robotics, and developed a drone mechanism they called DeLeaves that could collect plant material from treetops.

Their drone carried a tool suspended below it that can grasp and cut plants mid-air. DeLeaves proved highly effective for collecting plants directly below a drone, but could it be used on Hawaii’s sheer cliffs?

Excited by the chance to collaborate with the robotics team, we applied for a grant from the National Geographic Society with the hope of funding the development of a horizontal collecting arm. Our goal was to design a robotic arm that would enable us to collect seeds and cuttings from small, often fragile cliff dwelling species in Hawaii. When our application was approved, we quickly started the design process.

In our attempt to overcome the challenges of Hawaii’s extreme cliffs, we explored everything from long, extendable poles to semi-rigid vacuum hoses, and even one design that snapped like a clam shell. We were planning for our initial field trials when the COVID pandemic brought our work to a halt.

What at first appeared to be a major setback, later proved to be to our advantage. Travel restrictions delayed field trials for almost two years, but that allowed the team at the robotics lab in Quebec to build, test, and redesign the collecting arm without disruption. In the fall of 2021, as international travel was reopening, the team unveiled the MAMBA (Multi-Use Aerial Manipulator Bidirectionally Actuated). The draft design featured two independently functioning components — a lifting drone and the MAMBA mechanism.

MAMBA is suspended below the lifting drone but, unlike the earlier DeLeaves design, it has propellers that move the collecting arm forward and back like a pendulum. The device has a separate controller and remote video feed, allowing the MAMBA pilot to clearly see minute details within inches of the plant and cutting piece. The sampling head rotates in multiple directions, enabling the pilot the ability to align with and collect their branch of choice.

In October 2021, we initiated the first set of field trials on Kauai. Within a few hours of test flights in McBryde Garden, we felt comfortable deploying MAMBA into the wild. We were thrilled to find the device was stable, precise, and easy to operate. Focusing on target species such as akoko (Euphorbia eleanoriae), dwarf iliau (Wilkesia hobdyi), and hau kuahiwi (Hibiscadelphus distans), the MAMBA performed well, allowing us to secure collections from each species, in some cases from more than half a mile away.

Following our initial trial flights, the robotics team returned to Quebec where they continued to refine MAMBA. In March 2022 the team returned to Kauai ready to help us attempt to collect from target species which were particularly difficult subjects due to the plant’s growth habit or location.

These Kauai endemic species, all Critically Endangered, include Lysimachia inki, Kadua st-johnii, Lysimachia scopulensis, and laukahi (Plantago princeps var. anomala).

To better appreciate the challenges of collecting these extremely rare plants with this new technology, consider the case of Lysimachia iniki which grows on 3,000-foot high cliffs below Kauai’s summit, one of the wettest places on Earth. The extreme terrain and rainfall make this a particularly difficult area to operate drones.

After lugging the cumbersome equipment along muddy slopes and across a rushing stream, we were able to use a spotting scope to find plants with flowers and seeds. Climbing into the mist, the drone carried MAMBA to our target plants where we successfully collected a cutting from the sheer green wall and delivered it to us far below.

To our knowledge, the MAMBA collection of L. iniki was a first. The plant had been collected opportunistically after storms for the last 30 years, but our intentional collection yielded a large number of seeds from a healthy specimen, allowing us to deposit this invaluable collection to our seed bank and cuttings to our nursery where they rooted in captivity for the first time.

“Understanding the distribution and abundance of rare and endangered plants is a critical first step in their conservation.“

Ben Nyberg, GIS and Drone Program Coordinator

Another example of how drone technology is advancing rare plant conservation is our use of MAMBA to collect a sample from the extremely rare wahine noho kula (Isodendrion pyrifolium), a plant we were unable to identify by drone survey alone. After watching the MAMBA remotely cut and collect the plant, our excitement swelled as the drone returned. There is an undeniable thrill in extending one’s human hand to receive a botanical treasure from a robotic hand.

Previously documented on Niihau, Maui, Lanai and Hawaii Island in the mid 19th century, Isodendrion pyrifolium was thought to be extinct for more than a century until it was rediscovered on Hawaii in 1993. Another population was found on Oahu in 2015, but it was the MAMBA that allowed us to actually collect the species for the first time on Kauai.

Understanding the distribution and abundance of rare and endangered plants is a critical first step in their conservation. Drone technology makes this possible. Collecting seeds and cuttings from remote plant populations is the next step. Now drones can do that too. A third critical step in the conservation of plants is returning species to their natural habitat.

New projects now underway will eventually allow us to sow seeds onto inaccessible steep slopes. What we thought was impossible just five years ago is now reality. Armed with these new tools, a commitment to cooperation, and the determination to succeed, we are hopeful that these new discoveries will continue to positively impact plant conservation in Hawaii and far beyond.

Introducing the Mamba

Kauai, Hawaii

Researchers in Hawaii and Canada have developed a robotic arm that remotely collects endangered plants from high cliffs

Scientists at the National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG) in Hawaii, along with engineers at Outreach Robotics and researchers from the University of Sherbrooke in Quebec, Canada have designed a remotely controlled arm that can collect rare and endangered plants while suspended by a drone.

Their progress has been published in the journal Nature – Scientific Reports, documenting how the new technology is redefining rare plant conservation on high cliffs and other extreme habitat.

The partnership centers around an aerial robotic sampler roughly the length of a fishing rod equipped with eight propellers and a cutting mechanism which is suspended by a drone. The arm, called Mamba, can be operated remotely up to one mile (1.6 km) away. In flight trials, NTBG scientists and their partners have successfully collected seeds and cuttings from remote plant populations of extremely rare native species such as Lysimachia iniki and Isodendrion pyrifolium which grow on sheer cliff faces that are otherwise inaccessible.

NTBG drone specialist Ben Nyberg calls the technology “ground-breaking” and said, “this combination of robotics and botany is exciting, and is already having an amazing impact both in species conservation and the knowledge we’re gaining about cliff environments.”

Once retrieved by Mamba, the plants are recorded and brought to NTBG facilities where seeds are stored in a seed bank for conservation and research. Other seeds and cuttings are propagated in the nursery where they are grown and later used for restoration projects and returned to the wild.

NTBG nursery manager Rhian Campbell said the new technology can potentially increase success rates in growing rare plants because wild cuttings reach the conservation nursery much faster and in better condition than if they had been retrieved by hand. “The amount of time fragile cuttings spend under stress is minimized. Mamba allows us to collect multiple species very efficiently in a fraction of the time it used to take,” said Campbell.

NTBG is based on Kauai which is recognized as a biodiversity hotspot and is the oldest of Hawaii’s inhabited islands. Kauai is home to 255 plant species found nowhere else on Earth, nearly 90 percent of which are classified as Endangered or Critically Endangered based on IUCN Red List criteria. The remaining ten percent are extinct or nearly extinct in the wild.

For decades, NTBG botanists have used helicopters, rappelling, and rough terrain roping techniques to discover and collect plant material from some of the world’s rarest and most difficult to reach plant species.

Since 2016, NTBG has been using drones to discover rare plant populations previously thought to have gone extinct or otherwise unknown. NTBG’s collaboration with Outreach Robotics and the University of Sherbrooke in Quebec began in 2020.

Trial flights using Mamba include partnering with the State of Hawaii’s Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DOFAW) and the Plant Extinction Prevention Program. Adam Williams, a DOFAW botanist said, “Mamba has exceeded our wildest expectations, turning science fiction into reality. Surveying and collecting from a thousand-foot-high cliff from a mile away is just mind-blowing.”

Calling Mamba a “game changer,” NTBG’s Nyberg added, “it allows us to reach critically endangered species that are down to just a few individuals. It can be the difference between extinction and survival.”

The mission of the National Tropical Botanical Garden is to enrich life through discovery, scientific research, conservation, and education by perpetuating the survival of plants, ecosystems, and cultural knowledge of tropical regions.

Press kit with content and guidelines available here.

Learn more about the work of the National Tropical Botanical Garden at www.ntbg.org.

Learn more about NTBG’s drone program at www.ntbg.org/science/conservation/drones/.

Learn more about the work of Outreach Robotics at www.outreachrobotics.com.

For media inquiries, contact: media@ntbg.org

Kō (Saccharum officinarum)

Eye On Plants

Among the two dozen or so ‘canoe plants’ introduced to Hawaiʻi by the first Polynesian voyagers, sugarcane is one of the most widely grown in the tropical world. Called kō in Hawaiian, elsewhere sugarcane is known as to (Marquesas, Tonga), tolo (Samoa, Tuvalu), and dovu (Fiji). This sturdy member of the Poaceae (grass family) may have been first cultivated in Papua New Guinea, possibly originating as Saccharum spontaneum, a relative of S. officinarum.

Kō (Saccharum spontaneum) is valued for its sucrose-rich fibrous pulp which is used to sweeten food, drinks, and medicine or (as old-timers will tell you) cut fresh with a cane knife and chewed in the field. For early Hawaiians, kō was more than a sweetener. It provided thatching, mulch, compost, an ornamental wind break, and served as a soil stabilizer.

NTBG senior research botanist Dr. David Lorence first encountered sugarcane as a Peace Corps volunteer in 1970, working in a program of agricultural diversification with the Mauritius Sugarcane Industry Research Institute. Like Hawaiʻi, the southwest Indian Ocean island nation supported a vibrant sugarcane industry before it turned toward tourism.

Dave Lorence notes that while sugarcane has played a central role in the economies and development of many tropical countries, it also bears a darker history based on slavery and indentured laborers. Fortunes were made and empires built on the backs of laborers who toiled in cane fields doing back-breaking work, cutting and stacking cane by hand in dirty, sometimes dangerous conditions.

Furthermore, the industry was known for its insatiable (and often destructive) thirst for water, waste runoff, heavy fertilization, and industrial pollution. During harvest time, when drier, lower leaves were burned off the cane, Hawaiʻi’s skies blackened with soot and ash.

Hawaii’s own industrial sugarcane industry began on Kauaʻi in the town of Kōloa and quickly spread across the islands, fueling the migration of workers from Asia, the Caribbean, and beyond, leading to cultural and societal shifts that remain today.

Despite its checkered past, many in Hawaiʻi harbor deep affection for ko, and rue wistfully for the recent past when the days grew shorter, the cane grew taller, and its silvery tassels blew in the wind, signaling autumn harvest, the rising of the Pleiades (Na huihui o makaliʻi), and return of the Hawaiian Makahiki season.

In 2022, NTBG hosted Dr. Noa Kekuewa Lincoln, a Hawaiian crop specialist at the University of Hawaiʻi. Noa worked closely with NTBG staff to verify the provenance and identity of the Garden’s kō collection. Presently, NTBG has 11 sugarcane cultivars in McBryde Garden, eight at Limahuli Garden, and an estimated 27 at Kahanu Garden.

Kahanu Garden director Mike Opgenorth worked with Noa to verify cultivars and identify duplicates among the garden’s collection. Mike says that Hawaiian kō varieties have adapted to thrive in very specific microclimates which can make growing them together in one collection a challenge. With its mix of traditional Hawaiian cultivars and other, more recent ones, Mike says Kahanu Garden is a great place for people to experience the splendor of sugarcane growing in robust clumps.

Mike spoke of the importance of the plants in perpetuating cultural knowledge, naming a little-known variety called Koeli lima a o Halalii which translates as the hand-dug cane of Halaliʻi, a rare white-stalked cane known to grow in the sandy dunes along Halaliʻi, a seasonal lake on the island of Niʻihau. When exposed to the sun, the cane’s stripes turn lime green and iridescent pink. Nourished by Niʻihau’s freshwater springs and periodic rainfall from Mt. Paniau, the legendary ko is mentioned in the centuries-old stories and chants of Niʻihau

“The Hawaiians name everything and have a reason for doing that. Every wind and every rain has a name. Every cultivar of every canoe plant also has a name,” said Mike DeMotta. “But if you don’t know the name, you don’t know what you can do with it.”

A Global Partnership That Feeds

By Jon Letman, Editor

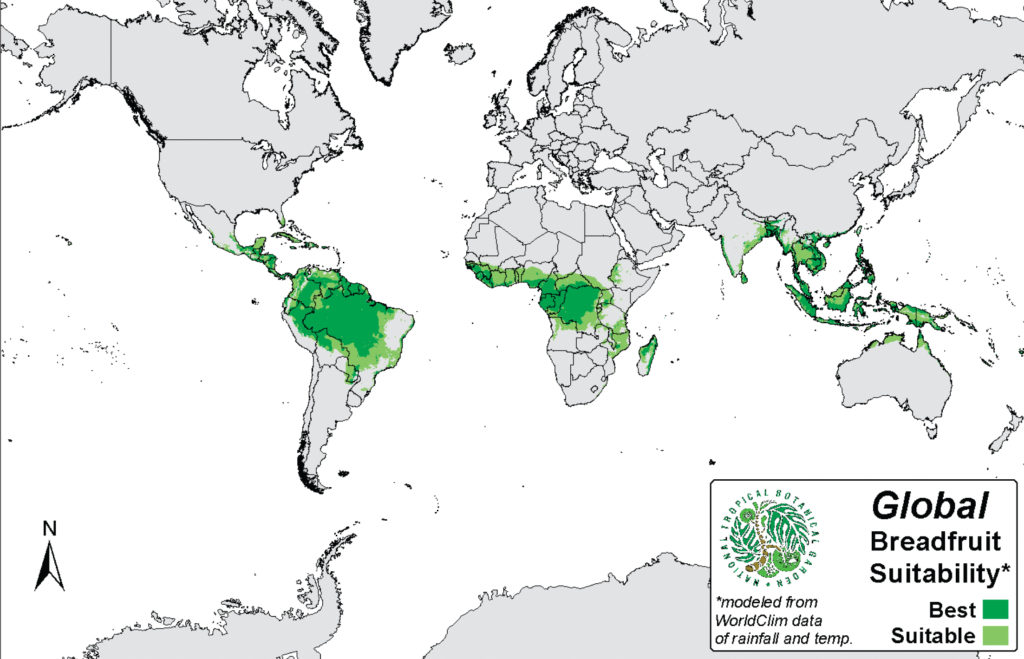

Posted on a wall in the office of the Breadfruit Institute at National Tropical Botanical Garden headquarters, a world map is marked by a bright green band indicating where breadfruit grows best. That band represents the potential to improve food security, increase reforestation, and bolster economic self-sufficiency.

One of the Breadfruit Institute’s most successful partnerships is with the Trees That Feed Foundation (“Trees That Feed”). Co-founded in 2008 by wife and husband Mary and Mike McLaughlin, two Jamaican-born breadfruit enthusiasts, Trees That Feed was established as a non-profit organization with the encouragement and support of NTBG Trustee Emeritus Douglas McBryde Kinney who also introduced Mary and Mike to Dr. Diane Ragone, director of the Breadfruit Institute.

Mike and Mary wanted to do something about climate change, environmental degradation, and global hunger, while creating economic opportunities. With breadfruit, they found they could address all.

As Trees That Feed grew, two promising breadfruit varieties—the Samoan Maʻafala and Tahitian Otea—caught Mary and Mike’s attention. After years of collaboration between Diane Ragone and Dr. Susan Murch, a plant chemist and tissue culture researcher at the University of British Columbia – Okanagan, Maʻafala and Otea were identified for their vigor, nutritional value, and suitability for mass micropropagation and global distribution.

Diane, who has spent more than 30 years studying and collecting breadfruit varieties from 50 Pacific islands, built the largest, most diverse collection of breadfruit varieties in the world. Since establishing a partnership with the Breadfruit Institute, Trees That Feed has distributed tens of thousands of micropropagated breadfruit trees originating from NTBG’s conservation collection to at least 18 countries and territories.

Since 2018, Trees That Feed has purchased breadfruit treelets from Tissue Grown, a California-based plant tissue culture company which grows the Breadfruit Institute-sourced Maʻafala that Mary and Mike have mostly donated to growers in Central America, the Caribbean, and Africa. A portion of the trees are sold commercially which helps support NTBG and the countries of origin.

South Pacific vibe

Tissue Grown’s president Carolyn Sluis explains how the tissue culture-raised breadfruit treelets are grown in peat and vermiculite plugs without soil. After acclimatizing in the greenhouse for six weeks, they are distributed around the world in flats of 72 saplings. Before the plants can be shipped, Tissue Grown must complete complicated and time-consuming shipping protocols through their local agriculture department. Once approved, the trees are sent by air and hand-delivered to overseas destinations by operations manager Karin Bolczyk.

Despite two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, Tissue Grown grew more than 100,000 Maʻafala and Otea in 2020-21. Last December, they shipped 1,800 Otea to Kenya with another shipment of three flats to Guinea in January 2022.

Calling Diane Ragone’s enthusiasm “infectious,” Carolyn hopes breadfruit will gain a foothold in more countries. For a company more accustomed to growing walnuts, pistachios, and cherries, breadfruit is somewhat unusual, but Carolyn and Karin agree that Maʻafala and Otea, with their “South Pacific vibe,” make breadfruit an irresistible feel-good crop.

Pacific connection

One of the farmers Karin has delivered breadfruit to was Nate Olive, owner of the 130-acre Ridge to Reef farm on St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands. In the aftermath of the category-5 Hurricane Maria which devastated the region in 2017, Nate shifted his focus to growing breadfruit to replace lost trees and which he says proved to be a great morale booster.

Coordinating with Trees That Feed and Tissue Grown, Nate has already distributed some 3,500 donated trees on St. Croix, St. Thomas, and St. John. In addition to local Caribbean White and Yellow varieties, Nate grows Ma’afala which he distributes to farms, home owners, and government properties in order to improve food security and local economic development.

Breadfruit was introduced to the Caribbean in the 1790s and has long been used in traditional dishes like callaloo, tostones, and monfongo. Although breadfruit is considered a local crop, Nate says, “We’re very respectful of the food and its identity…we feel connected with our brothers and sisters in the Pacific.”

Breadfruit for all

Five hundred miles southeast of St. Croix, on the island nation of Barbados, breadfruit is eaten with flying fish as a mash called coucou. Barney Gibbs, chairman for the Future Centre Trust, one of Barbados’s oldest environmental NGOs partners with Trees That Feed to provide for urban reforestation. Barney says importing breadfruit has allowed him to introduce greater horticultural variety to the island.

Since 2015, Barney has received three shipments of around one thousand Ma’afala which, he says, has proven to be popular for its compact, easy-to-manage. He adds that the pandemic has only made breadfruit more popular as a nutritious, reliable crop, and for use in value-added products like flour, chips, and other foods.

Barney’s main project is urban reforestation along a nineteenth-century railway line that was converted into a biking and walking trail. The Barbados Trailway project is being lined with breadfruit and other fruit-bearing trees, providing food for anyone who needs it. Other trees are given to local schools and community centers.

New to Africa

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, Catholic nuns in Kenya are harvesting what they call in Swahili shelisheli (breadfruit). Unlike in the Caribbean, breadfruit is a recent introduction. Joseph Matara, founder and executive director of the non-profit Grace Project (and Trees That Feed board member) welcomes the new crop. Joseph works closely with Mary and Mike to ship Otea and Ma’afala trees to Mombasa, Kenya, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Uganda’s Jinja district, north of Lake Victoria.

Like a handful of breadfruit trees believed to have been imported to Zanzibar from Goa long ago, breadfruit is proving to be best suited along East Africa’s coastal regions. Joseph has coordinated the donation of young trees to schools and other places where they are most needed. The high nutritional value and versatility of breadfruit make it ideal for improving food security. “For some of these children,” Joseph says, “what they eat at school is their only meal for the day.”

Other projects in West Africa (Ghana and Liberia) are taking root and Joseph sees great potential for breadfruit in Mozambique too.

Saving Lives in Haiti

At its core, the Trees That Feed Foundation is about helping people. Mary recalls shipping one thousand breadfruit trees to Haiti in July 2021. Those trees arrived less than 24 hours before Haiti’s president was assassinated, an event that led to great instability. One month later, Haiti was rocked by a 7.2 earthquake and powerful tropical storm which soaked the nation already upended by political violence, poverty, and COVID.

Mary says that after last summer’s earthquake, trees they had imported in 2012 proved to be a lifesaver when other food sources were cut off. “The work of NTBG helped us get established to where we could feed thousands of people in the area immediately around the epicenter of the earthquake.”

Mike adds the network between the Breadfruit Institute, Trees That Feed, and other partners is a testament to the power of breadfruit. “We are ecstatic about being able to collaborate with NTBG. We couldn’t do what we’ve done if they hadn’t helped us so much.”

Mary too says she’s grateful for the partnership. “If breadfruit can be the source of a job, an environmental benefit, and feed the world’s poorest people, then I think we’ve done a pretty damn good job.”

How a Garden Can Save a Stream

Restoration efforts in Limahuli Valley show how a garden can save a stream.

by Dr. Uma Nagendra, Conservation Operations Manager, Limahuli Garden and Preserve with Puakea Moʻokini-Oliveira, Conservation Technician

In the middle of Limahuli Stream, cold mountain water cascades down boulders into a hip-deep pool. I am grateful for the wetsuit keeping me warm. Small river stones slick with algae slip beneath my tabis (water shoes). If I stay still, I might feel the dull pinch of Tahitian prawns nibbling my toes. Looking up at Limahuli Valley, I can see both sides of the cliffs where koae (white-tailed tropic birds) dart into their nests. I don my snorkel mask, nod to lead technician Puakea Moʻokini-Oliveira, who is standing on the bank with a timer and waterproof datasheets, take a deep breath, and dunk myself into the frigid water to enter the aquatic world of freshwater fishes.

Immediately, several oopu nakea[1] dart away along the stream bottom, leaving silty clouds in their wake. As I step in their direction, I can see an oopu alamoo resting on a dark stone, its bright orange tail curled slightly against the rock contours. I almost miss the crowd of oopu nopili grazing on a patch of green algae because they are so close to the waterfall cascade.

This underwater survey is a component of The Haʻena ʻOʻopu Restoration Project, a two-year project funded by the Hawaii Fish Habitat Partnership in order to enhance stream health and oopu population numbers in Limahuli Stream. Freshwater aquatic species like oopu were once a major food source, although now few Hawaii residents have ever seen one.

While this underwater world may feel completely removed from the terrestrial world we inhabit at NTBG, they are actually intricately intertwined. Limahuli Stream is the thread connecting all parts of the watershed from mauka to makai (mountains to the sea). From the mist caught by the ohia (Metrosideros sp.) canopy in the uppermost valley, filtered down through moss, leaf litter and soil, flowing underground through porous rock, or overland in rivulets and gulches, all the valley’s water eventually follows Limahuli Stream to the ocean.

“In Many ways, the health of the stream indictes the health of the rest of the valley.”

Dr. Uma Nagendra, Conservation Operations Manager

Streams carry carbon, nutrients, and silt to the reef. Riparian ecosystems (streams and stream banks) offer unique habitats for plants and animals that are adapted to constantly moist, periodically flooded conditions. In many ways, the health of the stream indicates the health of the rest of the valley. Healthy streams also provide critical ecosystem services such as clean water, erosion prevention, and food.

With the abandonment of traditional stream management practices and introduction of invasive species, stream health has declined throughout Hawaii. Stream diversions, blockages, and invasive species overgrowth have adversely transformed many riparian systems that were once highly productive and biodiverse ecosystems.

Although Limahuli Stream is considered “pristine,” with high levels of biodiversity and among the least disturbed stream systems on Kauai, it is home to far fewer oopu than neighboring Hanakapiai Stream. A past comparison of the two suggests that the amount of sunlight reaching the streams could be a major contributing factor to the lower population in Limahuli. Native green algae are the foundation of the riparian food web, and thrive in high light conditions. A promising pilot study led by NTBG research associate Kawika Winter[2] several decades ago tested this idea on a small scale. The Hāʻena ʻOʻopu Restoration Project expanded that study in order to see if opening up longer sunny stream corridors (as would have been maintained with traditional stream management) would also increase green algae growth and oopu populations.

One of the main activities of this project was the selective trimming of Schefflera actinophylla, a highly-invasive tree species that threatens the health and resilience of the riparian ecosystem by preventing sunlight from reaching the stream, which limits green algae growth. The tree’s high evapotranspiration rates and inhibition of understory growth reduce groundwater penetration and storage, contributing to flash floods and erosion. Schefflera’s sprawling growth forms also threaten the integrity of valuable cultural resources. For this project, invasive trees were trimmed by an experienced local arborist crew (Haleleʻa Tree Service), with the help of Limahuli Garden staff.

Afterwards, Puakea and I started planting on the freshly cleared stream banks, with the help of many other Limahuli staff, KUPU service members, and volunteers. We hand-carried and planted over 4,742 native plants like kokio keokeo (Hibiscus waimeae hannerae), hala (Pandanus tectorius), and many others[3].

The mix of species was selected in consultation with previous restoration managers and living collections experts at NTBG. These included species sourced from northwest Kauai, quick to establish and grow in riparian areas, and which have strong root systems that will help prevent future erosion on a now-vulnerable stream bank. We also chose a few species that are likely pollinated by moths (scented, white, night-blooming flowers) in order to further promote moth habitat, including endemic Hyposmocoma and the opeapea (Hawaiian hoary bat) that feeds on them.

Throughout the project, Puakea conducted stream surveys to assess how the aquatic wildlife were responding to this change. The entire 1,500-foot restoration area was divided into three 500-foot sections where we swam for an underwater census of the aquatic animals. We also surveyed a cross-section of different parts of the stream to document the algal growth, substrate composition, and stream characteristics like water temperature, flow rate, and canopy openness.

Spending so much time along the stream banks allowed us to observe just how many other species enjoy this area as well. By investigating the lower stream, Puakea was able to note how hīhīwai[4] migrated up the stream into our restoration zone — and even spotted their small pink eggs on the rocks. While we planted or weeded, we were often joined by an aukuu (Black-crowned Night Heron) standing statue-like to fish on a nearby boulder, or a pair of Koloa maoli ducks playing in the current.

One of the best parts of this project was working with school groups, volunteers, and partnering community organizations. Although COVID precautions limited our interactions after the first six months of the project, we were able to welcome two recurring classes from Kanuikapono Public Charter School, a work-exchange with the Waipā Foundation, and a new stream research collaboration led by the non-profit Nā Maka Onaona.

Our results indicated that canopy openness alone was not enough to boost oopu population numbers within the time frame of this project. Aquatic animal diversity remained high, however, and indicators of stream health such as temperature were unchanged. By restoring the stream banks to native habitat, the stream corridor should now be even more hospitable to native birds, bats, and invertebrates, and safer from the invasive tree falls that exacerbated flood impacts in 2018.

The completion of this project is just the start of this important new restoration area. In order to sustain those benefits, we will need to continue maintaining the stream corridor. Ongoing collaborative stream monitoring will also help improve our understanding of watershed resilience both in the Limahuli Valley and in freshwater systems all across Hawaii.

Editor’s note: The author wishes to thank those who contributed significantly to this project: Kawika Winter, Ashley Ramelb, Saori Umetsu, Moku Chandler, Noah Kaaumoana, Pelika Andrade, Mackenzie Fugett, Lauren Pederson, Matthew Kahokuloa Jr., Kassandra Jensen, Joshua Diem, Emma Stauber, and others. Funding for this project was provided by The Hawaii Fish Habitat Partnership, which is coordinated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

[1] ʻOʻopu are species (Awaous sp.) of goby native to Hawaii. The three most common ʻoʻopu in Limahuli stream are ʻoʻopu nākea (Awaous guamensisi), ʻoʻopu alamoʻo (Lentipes concolor), and ʻoʻopu nōpili (Sicyopterus stimpsoni)

[2] Dr. Kawika Winter was director of Limahuli Garden and Preserve from 2005 to 2018.

[3] Including koaia (Acacia koaia), māmaki (Pipturus kauaiensis), ʻākia (Wikstroemia oahuensis), koʻokoʻolau (Bidens forbesii forbesii), and ground covers such as ahuʻawa (Cyperus javanicus), makaloa (Cyperus laevigatus), pili (Heteropogon contortus) and ʻaeʻae (Bacopa monnieri).

[4] Endemic freshwater snail (Neritina granosa)

Hawaii Education Series

Plants are the basis of healthy ecosystems from ridge to reef across Hawaii. The islands have truly unique and diverse ecosystems that provide our communities with a myriad of critical resources.

NTBG’s Hawaii Education Series provides students and families with fun and inspirational videos and activities exploring the plants, cultural resources, and people that make Hawaii special. Explore the videos below and check out more resources on our education page.

Hawaii Education Series: Ferns

Ferns are among the oldest living plants on the planet and play many important roles in their ecosystems, especially in Hawaii. Check out this video to get a quick overview of ferns in their natural environment, fern anatomy, fern lab propagation, and a fun experiment to do at home or in the classroom!

Hawaii Education Series: Canoe Plants

The landscape of Hawaii is filled with what we refer to as ‘canoe plants.’ These plants might even be growing in your school playground! So, what is a canoe plant? Canoe plants were brought to the Hawaiian Islands by our ancestors, the Polynesian voyagers. Check out this video to get a quick overview of canoe plants and a how-to on making a Ti (Ki) leaf lei.

Hawaii Education Series: Ahupua’a

Learn about traditional Hawaiian land management systems (Ahupua’a) through a virtual visit to NTBG’s Limahuli Garden and Preserve. Humans have inhabited and cared for Limahuli valley for over a thousand years. It is home to many of our native plants and animals like our native ʻaʻo, moths, ‘o’opu, laua’e ferns, papala trees, and so much more.

5 Reasons to Plant Native Plants

All native plants in peoples’ home landscape help preserve biodiversity. This is important for the future conservation of native species. Want to be a good neighbor to Hawaii’s native flora? Learn more about gardening with native plants at ntbg.org/gardening and do your part to save plants today.

Saving Spores

Often overlooked, ferns are a critical part of Hawaii’s native forest ecosystems and watersheds. Since 2007, the NTBG Fern Laboratory has been one of very few botanical research centers focused on the study and propagation of rare Hawaiian Ferns, which make up nearly 27.4 percent, or more than a quarter, of native flora. The need to understand and protect these vital species has never been greater. Read on to learn more about the Fern Lab, NTBG research, and how you can help save species today.

Hawai’i: Land of Pteridophytes

When you picture the flora of the Hawaiian Islands, colorful hibiscus, sweetly scented plumeria, and swaying coconut palms may be the first to come to mind. While important, these plants commonly associated with Hawaii are vastly outnumbered in native ecosystems by ferns. Across the islands, ferns dominate many niches in the wet, dry, and mesic forest environments. They absorb heavy rains, mitigate runoff, and provide habitat for native birds, moths, snails, and insects. Altogether there are 159 native species of ferns and lycophytes in the Hawaiian Islands, with 74 percent of those endemic to the islands.

The abundance and variety of ferns in Hawai’i are extraordinary, but so are the threats they face. Like many native Hawaiian plants, ferns are threatened by other plants, animals, disease, and loss of habitat. Ferns are particularly vulnerable because they lack defenses and usually grow low to the ground, near the mouths of hungry pigs, goats, and deer.

Saving Spores, Saving Ferns

Critically endangered Hawaiian ferns have been at the center of NTBG Research Associate, Dr. Ruth Aguraiuja’s work for more than two decades. Previously, as a senior researcher at Tallinna Botaanikaaed (Tallinn Botanic Garden) in Estonia, Dr. Aguraiuja’s desire to learn more about Hawaiian fern biology, ecology, and conservation methods has led to many breakthroughs as well as the reintroduction of hundreds of plants to their in situ habitat on Kauai.

Finding efficient propagation and conservation methods is critical to success because growing some native ferns can be time-consuming. In 2016, Dr. Aguraiuja shuttled hundreds of native Hawaiian Asplenium ferns propagated from spores in Estonia back to Kauai. Dr. Aguraiuja collected the spores in 2011 while botanizing in the high elevation forests of Kaua’i. In their early stages, ferns can grow very, very slowly, sometimes taking as long as two years to become a sporophyte and develop simple, tiny fronds. Thanks to Dr. Aguraiuja’s work and partnership, NTBG, staff, researchers, and interns have continued to utilize the Fern Lab to propagate rare, endangered, and culturally significant ferns from tiny spores, and to preserve genetic diversity needed to re-establish endangered populations in the wild.

Prior to the existence of the Fern Lab, propagation was primarily done through division (splitting of one plant into two or more by breaking the original in half with roots and crown attached to both halves). While division is a successful and efficient method for species with long creeping and branching rhizome (underground horizontal stems), each new plant is an exact clone of the parent. This does not promote genetic diversity, a key component in successful restoration and species conservation. Additionally, not all ferns species can be propagated in this way. By developing the protocols to grow ferns successfully from spores, we will be able to maintain the genetic diversity found in nature, and we will broaden our list of species, particularly the rare ones, that we can conserve and add to both ex situ and in situ conservation sites.

Today, spore propagation is taking center stage in the Fern Lab, but there is still much to discover about these hardworking Hawaiian plants.

Why Fund Fern Research?

Pristine areas of Hawai’i are covered in ferns, which makes them critically important to restoration and conservation efforts, but little research is happening on a large-enough scale to make a big impact now. “Ferns provide the foundation of functioning ecosystems in Hawaii and we still have so much to learn about them,” said Mike DeMotta, NTBG’s Curator of Living Collections. “For example, the time from propagation to outplanting varies across species. For some rare ferns it takes four years to go from gametophyte to plantlet. For others we can outplant within months to a year – this is why we need to support our Fern Lab, so we can learn how to best grow and care for our native species ex situ and in the wild.”

Providing additional support to the NTBG Fern Lab will go further than propagation and outplanting. It will also provide bandwidth for further study and continuity not previously available. “I am excited about the potential of what we can learn and do with full-time staff and funding in the Fern Lab,” said Mr. DeMotta.

In addition to the propagation of ferns, NTBG interns are currently looking at fern spores saved in the herbarium collection and conducting propagation studies to see if spores retain their viability after drying. When possible, fresh spores of the same species are collected and propagated in the Fern Lab and compared to the dried spores. “Our hope with this study is to be able to recover more fern species from dried collections that have become rare over time”, noted Mr. DeMotta.

The Need is Upon Us

Hawai’i is a biodiversity hotspot which means the islands, while biologically diverse, also suffer from a high rate of habitat and species loss. In other words, the need for enhanced support directed toward the conservation of floristic diversity in Hawaii and tropical regions around the world is great.

“We need a renaissance in conservation,” said Ken Wood, NTBG Senior Research Biologist. “Managing just one species requires so much support. To manage and restore entire ecosystems of threatened and endangered plants requires action today. Now is the time to spread the word. Get your friends, family, and organizations involved,” Mr. Wood continued.

NTBG is dedicated to tropical plant discovery, conservation and research. Our work includes conducting regional plant surveys, documenting and describing new species, publishing data, furthering conservation efforts through research, protection, and cultivation, and re-establishing populations of rare plant taxa in situ.

Funding the Fern Lab and protecting native ferns is just one of the ways we are saving plants and saving people. You can support these critical and comprehensive efforts to protect plants and tropical ecosystems worldwide with a gift today. Donate now.

Growing Gardenia Remyi

The propagation of a rare, endemic Hawaiian tree in the NTBG Conservation Nursery connects us to the past and shows us a way forward.

Born from volcanoes and shaped by wind, water, and waves, the Hawaiian islands evolved over millions of years to become some of the greatest biological treasures on Earth. What would we see, hear, and smell if we could travel back in time and explore Hawaii’s ecosystems as they were thousands of years ago? Perhaps we would see lush and multilayered forests protected by a tall canopy of trees that dapples sunlight onto the shrubs and dense understory below. We might hear sweeping winds and chattering branches punctuated by the chirps of colorful forest birds. The smell of damp soil, mist-covered leaves, and sweet, delicate floral notes might fill the air. It’s similar to what we might experience today with a few glaring absences.

The unique flora and fauna of the islands are declining at an unprecedented rate. With 90% of the 1367 unique plant species in Hawaii endemic to the islands, Hawaii sits atop the list of places with the most endangered and extinct species. The situation is dire, but we have the tools and resources needed to change course. NTBG and local, state, federal, and private conservation partners are connecting the science, conservation, and research dots to secure the survival of endangered trees such as the Gardenia remyi.

Gardenia Remyi

A member of the Rubiaceae (coffee) family, Gardenia remyi (known as Nanu in Hawaiian) is an endemic tree found on the Islands of Kauai, Molokai, Maui, and Hawaii. Its habitat ranges from mesic to wet forest, ridge shrubland, and wet cliff. The branches of Gardenia remyi are covered in minute, soft, downy hairs, and leaves cluster towards the tips of the branches. The flowers are white and fragrant with delicate cinnamon, vanilla, and coconut notes. Traditional uses of the orange fruit pulp include creating yellow dye for kapa cloth. With approximately 80 mature trees remaining in the wild, Gardenia remyi is Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List and threatened by displacement from nonnative plants, landslides, and reduced reproduction in the wild.

“it can be quite overwhelming and wondrous to discover new individuals of this large tree species”

“I’ve had the honor to work on the conservation of Gardenia remyi throughout its known range. Trees of this species have always been few and far between,” said Ken Wood, NTBG Research Biologist. “Currently the known number of wild individuals stands at around 80. Because there are so few trees remaining, it can be quite overwhelming and wondrous to discover new individuals of this large tree species, especially when they are in flower and fruit! I’ve observed Gardenia remyi in both wet and mesic conditions, and more often than not they occur in some of the most remote and isolated forests of the Hawaiian Islands. I feel a sense of relief knowing that there are numerous talented individuals working on preventing the extinction of Hawaiian Gardenia and others anonymously supporting conservation efforts,” Ken continued.

From Collection to Cultivation

When you think of rare plant conservation and saving species like Gardenia remyi, the image of field botanists like Ken rappelling over cliffs or adventuring through the wilderness to locate, document, and collect rare plants may come to mind. With more than 50 years of tropical plant research and conservation experience, it is certainly an image synonymous with NTBG.

However, botanizing, and collecting plants for study is only one piece of the complex plant conservation puzzle. Tucked into the Lawai Valley on the South Shore of Kauai, dedicated NTBG staff, volunteers and partners propagate and grow endangered species at the NTBG Conservation Nursery. At first glance, the Conservation Nursery looks like almost any other – sheltered in an unassuming, plantation-style building flanked by propagation tables and shade cloth. However, NTBG has collected or co-collected at least 19 endemic taxa believed to be extinct in the wild that are prospering in nursery conditions. Hawaiian species such as Delissea rhytidosperma, Kadua haupuensis, Kanaloa kahoolawensis, Stenogyne campanulata, and others might have gone completely extinct had it not been for NTBG efforts.

“At the NTBG Conservation Nursery, our focus is on providing quality care for threatened and endangered native plants.”

“At the NTBG Conservation Nursery, our focus is on providing quality care for threatened and endangered native plants. It is our role to be prepared at all times for any collection that may enter the nursery,” said Rhian Campbell, NTBG Conservation Nursery Manager.“ Gardenia remyi is one of those collections that needs a long-term approach to assist survival because there is little reproduction occurring in the wild,” she continued.

Thanks in part to a grant from Fondation Franklinia, a Swiss private foundation that supports the conservation of globally threatened trees, NTBG and partners have a unique opportunity to focus on native trees in need of critical conservation. Eleven species known to the Limahuli Valley, including G. remyi, with a remnant population of fewer than ten individuals have been chosen for the three-year study. Over the course of the project, NTBG will collect and propagate seeds to grow trees that can eventually be outplanted in the Limahuli Preserve to add genetic diversity to and reinvigorate wild populations.

A Learning Process with Signs of Success

Gardenia remyi has been growing in the Conservation Nursery periodically for decades, but until recently the trees had never thrived, in fact they appeared stunted, rarely flowered and many were lost to poor overall health. Since the Securing the Survival of the Endangered Endemic Trees of Kaua‘i, Hawai‘i project began in 2020, much has been learned about the soil amendments and conditions required to grow these rare and beautiful tropical trees ex-situ.

“Conditions in our low-elevation nursery are considerably different from conditions in the mountainous, higher-altitude interior of the islands where these trees are known to exist today,” remarked Hayley Walcher, Living Collections Assistant. “In addition, the environment in which these trees evolved has changed quite drastically since Polynesian Voyagers first arrived on the islands. As horticulturalists, one approach we can take is to try to imagine what conditions would have prevailed in those years before human contact and try to replicate them in the nursery,” she continued.

In recent scientific history, wild populations of Gardenia remyi have been documented along our ridgelines and forests. Therefore, before human contact, it is possible that G. remyi would have been found in landing and nesting zones for coastal and forest birds, where a significant amount of guano would be present in the soil making it rich in phosphorus, nitrogen, and other essential microbes. Operating under that hypothesis, nursery staff started to research the conditions in which the plants were likely to thrive and connect the dots with field botanists to better understand their habitat today.

“With knowledge of past and present habitats, we started to use natural soil amendments that encouraged the growth of microbes and fungi…”

“We noticed early on that our traditional method of growing plants in a sterile media with commercially available fertilizers was not supporting the long-term survival of Gardenia remyi,” said Rhian. “With knowledge of past and present habitats, we started to use natural soil amendments that encouraged the growth of microbes and fungi within our potting media, such as worm castings and mycorrhizal inoculants, and saw an almost instant response in the health of our trees.”

In January 2021 nursery staff conducted a few more informal experiments using native soils and other natural amendments as topdressing and within a few months new sets of leaflets emerged and the leaves darkened into a healthy, deep green color. Since then, staff and volunteers have consistently fertilized Gardenia remyi treelets with natural amendments such as worm castings, biochar, fish fertilizer, seaweed extract, seabird guano, composted manure, and mycorrhizal inoculant.

Everything is Connected

Hawaiian ecosystems are complex and interconnected biological communities which makes growing rare plants ex-situ a challenge. But, with signs of success starting to emerge for G. remyi in the nursery, the next step for staff was to determine the amount of water and drainage needed for the trees to thrive. “We used our understanding of the high drainage environments that they grow in naturally to adjust the media mix we were using, adding more cinder and perlite while also adding more peat moss to help lower the pH and better match the somewhat acidic conditions they prefer in the wild,” remarked Hayley.

With soil, water, and drainage conditions now carefully tailored for this species in the nursery, G. remyi quickly outgrew its space. Thanks to a generous donation, a new rare tree area was created in the nursery that allows staff to keep a close eye on the trees and protect them from fungal pathogens, spider mites, and other leaf-sucking insects.

Looking Ahead

While there is much to celebrate with Gardenia remyi today, challenges to plant reproduction and preserving genetic diversity still lie ahead. Only one G. remyi tree growing in the nursery is currently flowering; this tree was propagated via air layering from a mature, flowering tree while the others were grown from seed or cuttings from younger trees and are not yet mature enough to flower.

To further complicate things, plants generally employ strategies to ensure that they have the best possible mix of genetics present in their offspring, and without knowing which strategies are in use by a particular species, it can be tricky to determine how to time pollination or provide the necessary match-making environment to produce successful fertilization.

Trees in the genus Gardenia are often dioecious plants, meaning that trees often produce either male or female flowers. The nursery staff noticed that the flowers on our lone air-layered G. remyi tree seem to produce both male and female parts on the same flower. “This often means it is easier to produce self-fertilized seed, so it is unclear why we have been unsuccessful thus far.” said Rhian. “We have made attempts at self-pollinating the flower, pollinating a flower with pollen collected in the wild and brought to the nursery after a period of cold storage, and recently by mixing pollen from two flowers on the same tree. So far we have not been successful at producing seed, but will continue testing different pollination strategies,” she continued.

NTBG’s ex-situ collection of G. remyi trees represents only six trees from the wild and were propagated by a combination of cuttings, seed, and air layering. One of our immediate goals is to continue bringing these propagules of wild plants into cultivation to increase the genetic diversity of our collection. This will provide the best chance we have to plant enough healthy new trees that they will be able to produce offspring on their own again.

Humans and nature are inextricably connected. Protecting and restoring our natural ecosystems is one of the most promising climate solutions we can invest in to safeguard our future. The conservation story of G. remyi and other endemic trees in Hawaii not only connects us to the past but also shows us there is a way forward.

About NTBG

National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG) is a not-for-profit institution, dedicated to discovering, saving, and studying the world’s tropical plants and sharing what is learned.

Our network of five botanical gardens, preserves, and research facilities encompasses nearly 2,000 acres with locations in Hawaii and Florida. Thousands of species from throughout the tropical world have been gathered, through field expeditions, collaborations with other institutions and researchers, to form a living collection that is unparalleled anywhere.

Our collection includes the largest assemblages of native Hawaiian plant species and breadfruit cultivars in existence. Many of the species in our collections are threatened and endangered or have disappeared from their native habitats. In our preserves and beyond our gardens, NTBG is working to restore habitats and save plants facing extinction.

Our gardens and preserves are living laboratories and classrooms for staff scientists, researchers, students and visitors from all over the world. You’re invited to be a part of our team. Help us save plants and make a difference by joining as a member! Sign up by May 31, 2022, for a chance to win a VIP experience.

.svg)