New Art Exhibit at The Kampong honors Biscayne Bay’s Heritage and Future

Miami, Florida (September 6, 2023) — Bridge Initiative, a Miami-based environmental arts organization, has joined The Kampong of the National Tropical Botanical Garden to present the groundbreaking exhibition Biscayne. This collaborative endeavor showcases the vital role of contemporary art in advocating for the preservation and conservation of Biscayne Bay. The exhibition, curated by Bridge Initiative founder Katherine Fleming, features 35 local and international artists whose works cross disciplines to explore Biscayne Bay’s cultural, historical, and ecological significance.

“Amidst Florida’s record-breaking temperatures, I can’t think of a timelier art exhibition,” says Brian Sidoti, Director of The Kampong. “I am thrilled to collaborate with the Bridge Initiative as we bring the art and science communities together to give Biscayne Bay a voice.”

Biscayne Bay, a cherished subtropical lagoon stretching from North Miami to Card Sound, holds hidden histories and remarkable natural wonders. “In Biscayne, we tour the Bay’s treasures at The Kampong, one of the five botanical gardens of the National Tropical Botanical Garden that has immense historic and cultural significance for South Florida and beyond,” says Katherine Fleming, exhibition curator. “Through this multidisciplinary showcase, we aim to deepen our connection with Biscayne Bay and foster a future where nature and culture thrive harmoniously.”

Running from September 15th to December 2nd, 2023, Biscayne invites visitors to embark on an educational and visual journey that transcends art’s traditional boundaries. Visitors to The Kampong can enjoy the Biscayne exhibit included in the price of admission for a garden tour. Parking is limited and online reservations are strongly encouraged.

Maui-Hawaiʻi Fires

The devastating wildfires on the islands of Maui and Hawaiʻi have blanketed our islands over the past few days. We express our sadness and solidarity with all who are affected. While NTBG’s Kahanu Garden, located in Hāna, Maui is not directly threatened by the current fires, we are heartbroken for impacted family and friends.

The destruction of the culturally and historically important town of Lāhainā is unimaginable. As the focus remains on rescue and recovery, we encourage you to consider helping affected communities through a recognized aid agency such as the American Red Cross of Hawaiʻi or the Hawaiʻi Community Foundation’s Maui Strong Fund.

NTBG Internship Series: Kassie Jensen

Over half a century, NTBG has hosted hundreds of interns that have become leaders in plant-based careers. In this series, get to know a few of our former and current interns who are forging their paths in tropical plant science and conservation and creating brighter futures for generations of plants and people.

An eleven-month internship led to a lifelong passion, graduate school for Kupu member Kassie Jensen.

By Jon Letman, Editor

Growing up in California’s Inland Empire, Kassie Jensen was surrounded by citrus orchards. As a student, her interest in animal science led to learning about agriculture and eventually serving as a Peace Corps volunteer in West Africa. When the pandemic cut that endeavor short, a friend told her about Kupu, AmericCorps’ Hawaiʻi-specific conservation leadership development program.

With a growing interest in plants and tropical conservation, Kassie applied to be a Kupu member doing conservation and ecology work at Limahuli Garden and Preserve. Arriving at Limahuli in 2020, she says, was a “lucky coincidence.”

Although she originally planned to do only one eleven-month stint, she realized that Limahuli was where she wanted to be and what she wanted to be doing. After nearly two years working in Limahuli’s upper and lower preserve as a conservation technician, Kassie is preparing to start graduate school at the University of Hawaiʻi in the fall. Kassie talks about her involvement with NTBG below.

What were you doing when you started with NTBG at Limahuli?

I worked four days a week in the lower preserve and one day in the garden. We removed non-native plants and planted natives from NTBG’s south shore nursery. I also did stream surveys— counting oʻopu fish—and other restoration work.

Are you still doing stream restoration?

We aren’t counting fish anymore, but we are doing riparian restoration.

What was it like working inside Limahuli Stream?

I thought it was really fun. It was challenging at first—the stream was really cold and half the time it was raining—but my teacher, Puakea, was really great.

What is something meaningful that you learned as a Kupu member?

Working in the Lower Limahuli Preserve taught me about dedication to the work and kuleana (responsibility), and the strong work ethic of everyone here because this is the work we want to do—helping the community.

Did this experience change your relationship with plants?

In the Upper Limahuli Preserve, I became really enthusiastic about mosses. Once we did an all-day moss lesson. I am from a really dry desert-like area where we don’t have these beautiful, flamboyant mosses.

How did your interest in mosses begin?

One of my first days hiking around I saw this beautiful moss and said, “what is that?” It just spiraled from there. I am actually going to start graduate school in the fall at the University of Hawaiʻi to research mosses. I didn’t have any experience with moss before and now it’s my specialty and my life. I realized this is what I want to be doing and this is where I want to be. I am working as a research assistant for school through a lab doing research at Limahuli so I will be able to keep coming back.

Do you feel this internship has influenced your future academic plans?

Absolutely. Under the guidance of NTBG staff like Dr. Uma Nagendra who recognized that I was interested in mosses and said, “we should pursue this.” She had me start one project which led to another. That led to the publication of a checklist of the mosses of the lower Limahuli Preserve which has been accepted into Hawaiʻi biological surveys through Bishop Museum.

Did specific NTBG help guide you?

Yes, I consider the curator of the herbarium Tim Flynn and Uma as my mentors.

What is the value of supporting internships like the one you did?

We need people to be doing this work. We have to get people interested. Unfortunately, a lot of people don’t have the choice. Of course, it’s valuable because we really need to do this work if we want the island to remain this way. If we want to get people interested, they have to be supported financially.

People need plants. Plants need you.

Plants nourish our ecosystems and communities in countless ways. When we care for plants, they continue caring for us. Help us grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants.

Banking on Pollen

By Dustin Wolkis, Seed Bank Curator and Laboratory Manager

The value of education and training in science and conservation has long been recognized by NTBG. This can take form in many ways but usually involves students at various levels. In the fall of 2021, what began as a high school science fair experiment testing the limits of storing or banking pollen, turned into an international collaboration that has added another tool to NTBG’s expanding plant conservation toolkit.

Plant pollen, which many people associate with hay fever, is much more than an allergen. Pollen grains house the “male” reproductive cells of flowering plants. Pollination is the transfer of pollen from a stamen (the pollen bearing part of a flower) to a stigma (the externally pollen receptive part). The ability to store or bank pollen creates the opportunity for conservation practitioners to make controlled crosses between individual plants.

Dehydrated kanaloa kahoolawensis pollen grain image magnified 8,000 times. Photo by Radha Chaddah.

Pollen banking is a particularly useful conservation tool when plants are separated by distance which is common among rare species with fragmented populations or individuals. The same is true when plant reproduction cycles are separated by time which is increasing as climate change causes different flowering periods among individuals in the same species. Pollen banking can also aid botanists like NTBG conservation biologist Seana Walsh who is conducting research on how to minimize inbreeding among rare plant species such as the Kauaʻi endemic ʻālula (Brighamia insignis), found in collections at botanical institutions around the world.

Although NTBG has been banking pollen since at least 2016, until now there have been no studies on optimal pollen storage conditions. That is starting to change.

When trying to extend the longevity of pollen, as with seeds, desiccation (drying) pollen and airtight sealing in a low humidity environment is important. Moreover, if pollen can be dried, it can also likely be stored below freezing. If pollen is tolerant of both drying and freezing, its longevity can be extended many times over.

However, just as with seeds, pollen from different species behave in different ways when dried. Species-specific studies are needed to determine optimal storage conditions.

(L) Collecting pollen in McBryde Garden. Photo by Dustin Wolkis. (R) Pollen experimentation in NTBG’s seed lab. Photo by Katie Magoun.

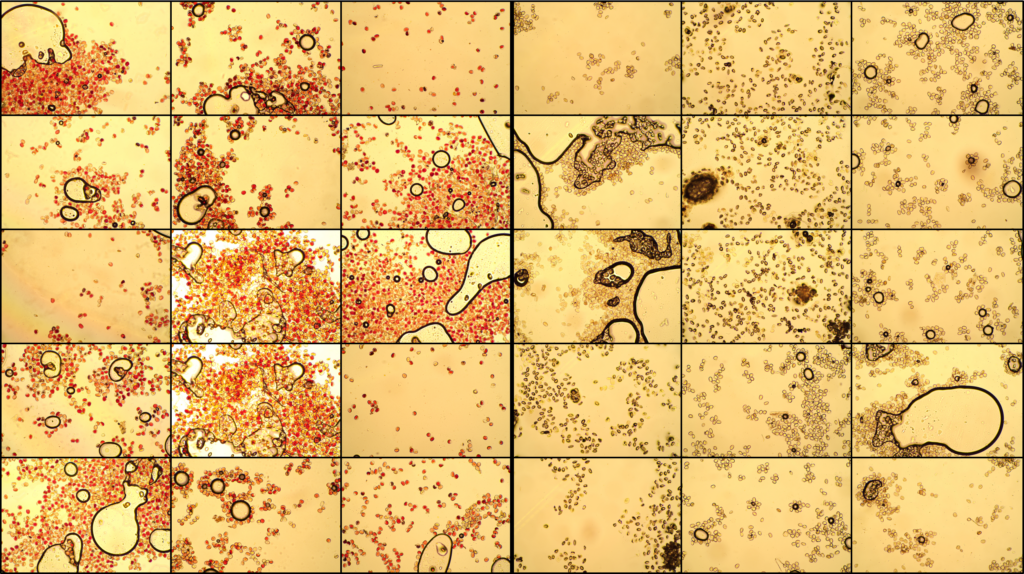

In 2021, a team of three highly motivated students from Kauaʻi High School became interested in pollen banking after visiting NTBG’s Seed Lab. They chose to study one of Kauaʻi’s endemic palm loulu species (Pritchardia minor). These students harvested pollen from NTBG’s living collections as part of their project. Their study was simple: dry pollen to three different levels and compare viability with a freshly harvested control.

Creating the media necessary for pollen grains to germinate can be exceedingly difficult, so the team employed a stain commonly used to assess viability in seeds. The first task was to test the stain’s ability to detect pollen that was once viable but is no longer so. To do this the team placed pollen in an oven and compared viability as assessed with the stain against that of the freshly harvested control. The stain did indeed detect the newly dead pollen and so could be used for the desiccation tolerance experiment. The team found that Pritchardia minor pollen could be dried down to international standards, which is great news for the long-term pollen conservation of the species. The team also placed dried pollen at freezing temperatures before concluding their project.

Ultimately, the students’ project won several awards at the Kauaʻi Regional Science and Engineering Fair, including first place in the Biological Sciences category, leading them to advance to the state level competition where it won first place in Plant Sciences.

Panels representing single microscope views of pollen after oven treatment. Photo by NTBG staff/partners.

Several months later when Caroline Reize, a recent agro-ecology graduate from University of Cologne in Germany, contacted me about doing an internship in plant conservation at NTBG, I envision the dried and frozen pollen samples as the perfect project. Upon her arrival, Caroline focused on completing the high school pollen banking project as well as gaining firsthand propagation experience with conservation nursery manager Rhian Campbell.

Serendipitously, Caroline’s research stay at NTBG mirrored that of Danish Botany undergraduate student Clara Gråfelt Thomsen, allowing the two to room together. Clara had come to NTBG to observe pollination in two Hawaiʻi endemic species, ʻālula and maiapilo (Capparis sandwichiana) and so, with Caroline studying pollen conservation and Clara studying pollination, it was only natural that the two would help each other by “cross-pollinating” on their respective projects.

Clara and Caroline not only completed the high school freeze-tolerance portion of the project, but also started new pollen conservation projects using ʻālula and maiapilo. They had to figure out which stains to use for each species, and even attempted several recipes for germinating ʻālula pollen. The team also studied pollen longevity after drying to different levels. This research paired well with two master’s students conservation projects on the same species, respectively, that were already underway.

Although the results of this work are forthcoming, we have generated valuable data that will aid in the conservation of rare Hawaiian plant species. By working with students at three different levels (high school, undergraduate, and graduate) we have learned more than we could have on our own. Furthermore, this may have implications for global pollen conservation. NTBG will continue to increase our knowledge and experience in pollen banking, giving us another important tool to stem the tide of plant extinction.

People need plants. Plants need you.

Plants nourish our ecosystems and communities in countless ways. When we care for plants, they continue caring for us. Help us grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants.

NTBG Internship Series: Emily Saling

Over half a century, NTBG has hosted hundreds of interns that have become leaders in plant-based careers. In this series, get to know a few of our former and current interns who are forging their paths in tropical plant science and conservation and creating brighter futures for generations of plants and people.

Kupu member Emily Saling reflects on her experiences in NTBG’s seed bank and laboratory.

By Jon Letman, Editor

Portlander Emily Saling was a sophomore on a medical track at the University of Puget Sound when she took an elective class that sparked her interest in plant conservation. That class opened her eyes to the idea of plants as a career path. Shortly before graduation, her biology professor told her about an AmericCorps Hawaiʻi-specific conservation leadership development program called Kupu.

As a Kupu member, Emily applied for and accepted a position similar to an internship at NTBG’s seed bank and laboratory on Kauaʻi. Since September 2021, Emily has worked as a seed lab conservation technician with NTBG staff.

Through the Kupu program, Emily and others like her are gaining practical conservation skills, leading complex projects, and collaborating with other Kupu members. Now in her second 11-month Kupu term, Emily is considering her next steps for when the term ends. Emily is exploring conservation positions with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or possibly working for a non-governmental organization in conservation.

Emily spoke about her involvement in the Kupu program and her experience working at NTBG’s seed bank and laboratory.

Will you continue working in seed conservation after you leave NTBG?

I don’t know, but I like seeds a lot. NTBG’s seed bank curator and laboratory manager Dustin sent me information about a seed stewardship program which sounds really interesting. It would be cool to learn a whole new flora of a different region. Seed conservation is a really niche thing but I feel like I have such a strong foundation now, I would like to keep building on it.

How did you develop this strong foundation in seed conservation?

From working in the NTBG seed lab. I had a basic knowledge of plant physiology but coming into work every day I learned something new. It’s been really interesting to learn so much about a field completely new to me.

What is it that you like about working with seeds?

In this position I’m able to figure out what conditions are best for these seeds. It’s like a puzzle and a mystery. Once you figure it out, you’re home free and can make all the baby plants you want. It’s exciting that at NTBG we’re able to send the seeds down to the nursery where the plants can mature.

How do early career opportunities like the Kupu program contribute to the perpetuation of plants, ecosystems, and cultural heritage?

I think with Kupu and even more so at NTBG, people already have such a passion for plants, so working with likeminded people really encourages me to keep going. We’re given a lot of opportunities here to try different aspects of conservation. Being on Kauaʻi, you see the flora and talk to people who have watched species go missing and you can’t help but want to be on the ground and be part of it. Learning leadership skills through Kupu and at NTBG definitely encouraged me to keep going.

How has the Kupu program and your connection to NTBG influenced your expected future career path?

I don’t think I would have thought about working with seeds before coming to NTBG. Also, I didn’t realize there were so many positions in conservation. There’s always something new to be involved in. I see opportunities that I didn’t know were available before.

Why should people support Kupu and other intern programs at NTBG?

Kupu specifically does a really great job of keeping people engaged and creating different opportunities. We already come in with a passion for conservation so to give us a big opportunity to learn, gain mentors, and network with people is so valuable. I feel incredibly lucky to be in this program. I hope that people continue to be a part of it because it’s so crucial at this time in our history, and there’s so much still to be learned.

People need plants. Plants need you.

Plants nourish our ecosystems and communities in countless ways. When we care for plants, they continue caring for us. Help us grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants.

NTBG Internship Series: Barbara Herrera

Over half a century, NTBG has hosted hundreds of interns that have become leaders in plant-based careers. In this series, get to know a few of our former and current interns who are forging their paths in tropical plant science and conservation and creating brighter futures for generations of plants and people.

Barbara Herrera’s internship at The Kampong helped reaffirm her passion for tropical botany.

By Jon Letman, Editor

Raised in Miami’s Little Havana neighborhood, Barbara Herrera attended Florida International University where she earned a bachelor of science degree in environmental agriculture in 2020. Through one of her professors, she met Dr. Christopher Baraloto, Director of the International Center for Tropical Botany (ICTB) at The Kampong. He introduced Barbara to a citizen science collaborative tree data collection initiative called ‘Grove ReLeaf’ which led to her learning about an internship offered at The Kampong.

For two years, Barbara worked as a research assistant intern at The Kampong where she also did a tropical botany internship at the ICTB. Her work included identifying and measuring trees in the surrounding area, contributing to the creation of a food forest booklet, and other community outreach through workshops and seminars.

Currently Barbara is working toward a Master’s Degree at the University of South Florida in Tampa where she is focused on Latin and Caribbean studies which will benefit her as she pursues a career in ethnobotany in the Caribbean. Barbara spoke about her experience as an intern at The Kampong.

How did your internship relate to your previous studies?

I saw ICTB at The Kampong as an extension of the things I had already been doing and as a resource of global communication between botanists. There are so many opportunities to expand in an educational direction.

Has your experience with FIU and the ICTB at The Kampong steered you in a particular direction academically or professionally?

These communities and organizations were all linked in one way or another and it was on me to figure out what those links were. These are opportunities that were available and the tropical botany course at ICTB at The Kampong was phenomenal as it was centered around both international and local students. It definitely feels like all of these have made me a better academic and I continue to be influenced by all that I learned.

How did staff at the ICTB and The Kampong help you along your path?

Christopher Baraloto, Benoit Jonckheere, and other staff made me a more well-rounded individual. Their different approaches to horticulture and plant science, as well as their backgrounds, gave me a range of possible paths to pursue under the umbrella of plant science. They were always willing to provide suggestions that helped me make academic decisions toward my educational goals. They were, and continue to be, mentors to me.

How has your experience at the ICTB and The Kampong impacted your relationship with plants and nature?

Through the internship at The Kampong it was refreshing to learn about the ethnobotany of Hawaiʻi too. This helped reaffirm my passion for tropical botany. Ultimately, it was about the setting. Being surrounded by tropical flora 24/7 was everything to me and I grew closer to the plants around me as I interacted with them.

Do you plan to remain involved with ICTB at The Kampong in the future?

Definitely. I would love to do research based in the Caribbean, specifically the Dominican Republic. I feel like Miami is part of the Caribbean, so I see myself working with NTBG staff again. I try to stay connected with what’s going on at The Kampong as it has been a major source for friends and education for me.

Why should someone support internships at The Kampong and ICTB at The Kampong?

If I hadn’t gotten paid I wouldn’t have been able to dedicate the 40 hours a week for the internship. Also, for the tropical botany course, I was given a scholarship and that helped me by not needing to have another job. Thankfully, I have been funded as it makes it more accessible. Botany and other science fields have been neglected for too long so now I think it’s up to people with financial means to pay attention again and say, “maybe we need this field to flourish in a more substantial way.”

People need plants. Plants need you.

Plants nourish our ecosystems and communities in countless ways. When we care for plants, they continue caring for us. Help us grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants.

NTBG Internship Series: Rocío del Mar Rivera Ramos

Over half-a-century, NTBG has hosted hundreds of interns that have become leaders in plant-based careers. In this series, get to know a few of our former and current interns who are forging their paths in tropical plant science and conservation and creating brighter futures for generations of plants and people.

Rocío del Mar Rivera Ramos grew up hearing her father’s experiences as an NTBG intern. Thirty years later, she followed in his footsteps.

By Jon Letman, Editor

As a child growing up in Puerto Rico, Rocío del Mar Rivera Ramos often listened to her father recall his experience as an intern at the National Tropical Botanical Garden 30 years earlier and 6,000 miles away. In 2022, while pursuing a degree in general agriculture from the University of Puerto Rico – Mayagüez, Rocío decided to follow in her father’s footsteps and applied for the same internship still offered by NTBG.

Rocío del Mar Rivera (left) completed an NTBG internship just like her father 30 years before her (right).

Hawaiʻi was the furthest she had traveled from home so when she arrived on Kauaʻi, Rocío was excited to see this foreign landscape she had heard about for years. During the twelve-week-long internship, Rocío was able to build on the knowledge and experience she had already gained growing up on her family’s 25-acre farm where they cultivate coffee, vanilla, and Puerto Rican native trees.

When Rocío graduated from NTBG’s fall internship, her parents flew out to help her celebrate, giving her father a chance to see the garden that had been so important to him. Rocío was thrilled to walk with her parents amongst breadfruit trees that had been planted by her father decades earlier. Back in Puerto Rico, Rocío plans to pursue a career that combines agriculture, conservation, and entrepreneurship. She spoke about how NTBG’s internship has influenced her.

What are your plans after graduation?

I really want to work with my dad on the agroforest we are developing on our farm. I also would like to continue my studies, maybe in entrepreneurship or agroecology.

Knowing your father had been an intern at NTBG 30 years earlier, how did you feel when you arrived on Kauaʻi?

I was really excited. It was very special because my parents flew out to Kauaʻi for graduation. My dad could see all the differences that had taken place. One really special thing was when my dad showed me the breadfruit trees he planted as an intern. I had the chance to cultivate and eat from those same trees.

You eat breadfruit in Puerto Rico, right?

Oh my goodness, yes! We call it pana or panapén. To be honest, before the internship I had a breadfruit tree in my backyard but we only ate fried tostones or boiled pana. But in Hawaiʻi, it blew my mind how diverse it can be. In Puerto Rico we just boil or fry it. I saw how much you can do with breadfruit—it was amazing. I would really love to work more with breadfruit. I am also considering getting more into agricultural research to see if the field suits me.

What did you find similar or different between Hawaiʻi and Puerto Rico with regards to conservation?

In a way, Hawaiʻi is more conscious about conserving native species. I want to share what I learned with people here in Puerto Rico about how Hawaiʻi conserves its natural resources.

What impressed you most about your internship at NTBG?

I feel like professionally this experience reassured me that agriculture and horticulture is the thing I want to do. It’s a really humble job, but it’s also really gratifying in the end.

Have you told friends and classmates in Puerto Rico about being an intern at NTBG?

When I came home, lots of people asked me about my experience. I told them how it changed my life. I learned so much at NTBG. I would really love to tell everyone at my university about this internship because I believe that a lot of people here in Puerto Rico can benefit.

For people wondering why they should support NTBG internships, what would you tell them?

I feel like there are not many programs as unique as NTBG’s. I hope this program continues because for me, I learned what I want to do for the rest of my life. Perhaps future NTBG interns can discover his or her passion too.

People need plants. Plants need you.

Plants nourish our ecosystems and communities in countless ways. When we care for plants, they continue caring for us. Help us grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants.

Welcome to Ulutopia

Breadfruit Institute inspires college project

By Jon Letman, Editor

Since its establishment in 2003, the mission of NTBG’s Breadfruit Institute (BFI) has been “to promote the conservation, study, and use of breadfruit for food and reforestation.” Among its chief goals has been to encourage the use and understanding of breadfruit — called ʻulu in Hawaiian — so that it can best achieve its potential.

Today that goal is being realized through Ulutopia, a project run by the staff and faculty of Kaua‘i Community College (KCC). The project is centered around a three-acre plot of land divided into four quadrants, each with sixteen breadfruit trees. Since the trees were planted in 2016, Ulutopia has proven to be a popular outdoor classroom for local students and visiting researchers, as well as a source of abundant, nutritious food that is feeding the community.

(L) ʻUlu fruit. (R) Brian Yamamoto standing alongside ʻulu trees in Ulutopia.

Ulutopia’s genesis involved Breadfruit Institute director emeritus Dr. Diane Ragone and KCC faculty Brian Yamamoto and Sharad Marahatta sketching out ideas on a whiteboard with input from experimental design by BFI partner Dr. Susan Murch of the University of British Columbia – Okanagan. Brian, the project faculty lead and a professor of botany and microbiology, encouraged Sharad to develop the plan who came up with the name. Together they purchased a box of 64 tissue cultured five-gallon treelets — all Ma’afala — a Samoan variety which had been selected and carefully developed for mass distribution after years of research by Diane, Susan, and others.

Planted neatly in rows in what had previously been weedy, fallow land once used for growing sugarcane, rainfall and hand-trucked water provides are the site’s only irrigation. Walking between the leafy trees, Brian describes the value of the project for visiting researchers.

“There’s a group from New York running microbiological studies of the material under the mulch looking at carbon sequestration,” he says, mopping his brow on a muggy autumn morning.

A group of students from a technical college visiting from Japan used the site to practice measuring moisture content, temperature, and other indicators using ground sensors. Other researchers from the University of Hawaiʻi collected leaf samples to measure the impact of fertilization practices.

One observation confirmed by measuring nutrient levels in soil and water, Brian says, is that because Ulutopia was planted on a slight grade, fertilizer and water flowing down slope have produced larger yields and larger trees than those growing up slope. With fertilization, Brian adds, the fruiting cycle has been extended to nearly year-round production.

With such high yields, and because Ulutopia is supported by a federal grant, Brian explains that KCC donates all its harvests, supplying thousands of pounds of breadfruit to the Food Bank of Hawaiʻi, school cafeterias, and Kauaʻi’s primary hospital for use in its dining facilities. Previously the hospital purchased and imported frozen breadfruit from Hawaiʻi Island, but now serves breadfruit harvested just a few miles away. KCC also uses young breadfruit trees that rise from spreading root suckers for an annual community tree giveaway.

Ulutopia’s fruit is used for value-added projects including one that uses a commercial drier and grinder to make ʻulu flour, enabling the college to provide free flour to local bakers and KCC’s culinary program so they can experiment and gain proficiency before purchasing ʻulu flour in the commercial marketplace.

Kauaʻi entrepreneur Dominque Chambers, owner of Cozy Bowl, a company specializing in breadfruit pasta (ʻulu campanelle, fusilli, rigatoni, etc.) relies on local ʻulu production, so when Ulutopia donated some 800 pounds of its fruit last autumn, she dehydrated what she could for flour, freezing the rest. Dominique, who has enthusiastically volunteered at NTBG, donates her time and sells a portion of her pasta at very low cost to support Nourish Kauai, a small Kauaʻi non-profit organization which provides chef-curated meal kits (more than 77,000 meals) to qualifying kupuna (grandparents/elders) in need.

Dominique, an ardent ʻulu advocate, is a model of what the prioritization of breadfruit looks like. She says Ulutopia is “really powerful in terms of getting young people to become emotionally invested in farming ʻulu.” With a growing need to bolster food security in Pacific Island nations, she sees limitless potential in helping small and vulnerable communities.

Photo by David Bryant

Meanwhile, Ulutopia serves as a learning space for Kauaʻi youth. Trineen Lopes Lacaden and Shannon Pabo, instructors with KCCs Cognition Learning Center (“Cogs”), regularly introduce young students to botanical, horticultural, and other STEM subjects at Ulutopia where K-12 students learn to take measurements, collect data, and other horticulture an agriculture basics. Ulutopia also gives students from Hawaiian language charter schools the opportunity to interact with an important heritage crop.

Trineen says the most popular lessons revolve around eating, noting that students pay closest attention when they are active and touching the fruit, adding, “it’s tangible and they’re in the field, it just makes more sense and they’re more excited.”

Asked if Ulutopia would exist without the Breadfruit Institute, Brian answers emphatically: “No. Easily no. The only reason this came about was my connection to NTBG.” From its importance as a place for research and teaching, to the cultural knowledge perpetuated and vital food being provided to the community, Ulutopia offers a template that others can model and replicate in a space as small as half an acre.

After NTBG’s Mariella Mladineo, an agroforestry technician with the Breadfruit Institute, was given a tour of Ulutopia, she says it increased her appreciation of how the common goal of elevating breadfruit’s prominence can be achieved in many different ways. While Ulutopia’s approach differs from the BFI, the end goals are very similar. “At the Breadfruit Institute, we look forward to future collaborations with programs such as Ulutopia,” Mariella says, “to learn from each other and build on our shared knowledge.”

People need plants. Plants need you.

Plants nourish our ecosystems and communities in countless ways. When we care for plants, they continue caring for us. Help us grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants.

The Fertile Soil of Memory

Renewing the future for cherished plants by tending our past

By David Bryant, Director of Communications

Nani wale nā hala ʻeā ʻeā o Naue i ke kai ʻeā ʻeā …so begins Nā Hala O Naue, a famous ode to a cherished grove of hala (Pandanus) trees that once shaded Naue Beach on Kauaʻi’s North shore. But today this forest “drenched in fragrance” and “swaying close to Hāʻena” has been all but lost.

The iconic hala tree spirals skyward atop stilt-like roots, their leaves exploding in tropical rosettes. These leaves are literally woven into Hawaiian culture, used for sails, baskets, apparel, and much more.

Hala’s chunky yellow, orange, and muted brown fruits add to the plant’s flamboyance. But it’s the elegantly small, red fruit for which Naue hala is renowned.

What happened to the beloved hala grove of Naue? Siblings Violet Hashimoto-Goto and Thomas Hashimoto, born in Hāʻena in the 1930s, say many of the trees were destroyed by a tsunami in 1946. NTBG’s former president Chipper Wichman adds, “When I was growing up, the tidal wave of 1957 had just occurred and Naue had been completely flattened. The combination of the two tsunamis did indeed wipe out all that remained of the hala grove at Naue.”

Lei Wann, director of Limahuli Garden and Preserve, whose family is from Hāʻena, has spent decades in search of the elusive Naue hala. For her, reviving these trees is a vital component of preserving her community and culture. “These plants hold stories and reawaken our genealogical connections,” says Lei. “They are living artifacts that transcend time and weave our stories together.”

(L) Lei Wann, director of Limahuli Garden and Preserve. Photo by Erica Taniguchi. (R) The red fruit of the Naue Hala.

Growing up, Lei heard murmurs about Naue hala still found in backyards and in memories. These leads would surface, only to vanish. There was fear that the famed red hala of Naue was forever lost.

When Lei celebrated her son Hanalei’s high school graduation, hala lei were everywhere. Hala in Hawaiian signifies “to pass.” The garlands of hala are a deeply symbolic gift representing a passage or transition. As they celebrated, Lei’s family sang and reminisced about the Naue hala grove, recalling the tree’s red fruits. At that moment, Hanalei’s father shared an epiphany with Lei: didn’t the hala trees growing on their Kalapana home on Hawaiʻi Island also have red fruit?

He recalled decades earlier when a family friend, the late kumu hula and lei master Dana Valeriano “Kauaʻiʻiki” Olores, presented a red hala lei at the funeral of Lei’s mother-in-law on Hawaiʻi Island. On that solemn occasion, the lei, made with fruits from a tree on Kauaʻi, symbolized the passage and transition after death. He remembered his brother had buried the fruit from the red hala lei in the yard at Kalapana. A quarter of a century later, prompted by these memories, Lei traveled to visit the hala tree that had sprouted at Kalapana. It was full of red fruit.

Today more than 50 descendants from the hala of Naue are being grown in Limahuli Garden’s nursery. Many of these young trees will be given as a gift for use in a restoration project by the YMCA camp at Naue Beach.

Dress by Rocket Ahuna modeled by Helena Ng. Photo by Kilikai Ahuna.

As the Naue hala reawaken in Hāʻena soil, community connections to this plant and place are coming alive too. After Lei shared her story of the Naue hala with Hāʻena descendant and fashion designer Rocket Ahuna, he was inspired to create a dress that reflected the trees and the spirit of the land in its design. That dress won the Critic’s Choice Award at the 2022 Fashion Institute of Technology exhibition in New York.

Lei said that by sharing the seeds and her story of Naue hala, Rocket could connect with his past to “see what our ancestors were seeing when they wrote songs or perhaps made clothing inspired by these same trees.”

Lost and found

Like the family memories that changed the fate of Naue hala, another recollection helped save a species known only from the precipitous sea cliffs of Kauaʻi and Niʻihau.

That plant is the ʻālula (Brighamia insignis), a remarkable succulent which is now believed to be extinct in the wild. However, thanks to the extreme measures NTBG staff and others have gone to preserve it, ʻālula now number in the thousands in gardens and nurseries worldwide.

Steve Perlman with a wild ʻālula in 1978.

Although the story of ʻālula has become closely associated with NTBG’s history, few have heard a nearly forgotten chapter of how family memories aided in the conservation of this imperiled species.

In the 1970s, Chipper Wichman and Steve Perlman spent years searching for the elusive ʻālula. Despite reports that the plant was growing on Kauaʻi’s Hāʻupu mountain range, their surveys had been fruitless. Their luck changed when Chipper’s grandmother Juliet Rice Wichman recounted how, as a young girl around 1910, while attending a lūʻau at the canoe club in Nāwiliwili, she saw two boys swim across the Huleʻia Stream. When they returned, they had collected ʻālula from the bottom of a cliff.

Based on this memory, Chipper and Steve mapped out possible locations and, aided by the decades-old story, discovered 12 new plants. The recollection of memory played a critical role in saving the ʻālula.

Goddess of the forest

Just as our memories can preserve our relationships with plants, so too can they illuminate new paths forward in the conservation of endangered flora. Mike DeMotta, NTBG’s curator of living collections, is an expert in the cultivation of Hawaiian plants who brings together decades of horticultural experience and generations of ancestral plant knowledge.

Mike’s early love for plants was shaped by hula, an aspect of Hawaiian culture deeply rooted in plants. Laka, goddess of both hula and the forest, is embodied in plants like ʻōhiʻa, hala pepe, and palapalai ferns. The dances, songs, and chants that Mike learned in his hula practice are homages to these beloved plants.

Mike DeMotta, NTBG’s curator of living collections. Photo by Neal Uno.

In his youth, Mike gathered plants in the Koʻolau Mountains for making lei. He also observed his elders use plants as herbal remedies, and listened to the moʻolelo (stories) of the plants like kalo (taro) and ʻuala (sweet potato) that sustained his ancestors. Decades later, Mike cares for plants guided by a philosophy that weaves together these cultural and ecological connections.

“I’m interested in native plants because of the inseparable bond between them and early Hawaiian culture,” Mike says. “I feel responsible for doing whatever I can to perpetuate native plants because they are an important part of the ecosystem.”

Today, Mike can often be found in NTBG’s Fern Lab, surrounded by sporelings from both common and critically endangered species. While ferns provide critical ecosystem services and are integral to Hawaiian culture, horticultural knowledge on growing these species is still relatively limited. To propagate native ferns successfully, Mike has relied on the memories and legacies of many collaborators. As he works amongst the ferns in the lab, Mike takes comfort knowing that he is surrounded by Laka as she comes to life in the many pots and growing containers around him. She nurtured him, and his ancestors, through hula and a lifetime in the forest. He is happy and committed to returning the favor.

NTBG represents an invaluable sanctuary for biocultural diversity. Successfully growing the world’s rarest plants and restoring them in their natural habitat and in managed settings, requires technical skills, life-long commitment, and resources. It also demands a respect for memories passed on by ancestors, elders, and present-day partners. Nourished by these memories and bolstered by a commitment to preserving culture and community, NTBG continues to perpetuate plans and the ancestral knowledge to sustain them.

As we work together to restore relationships between plants, places, and people, our path forward is constantly illuminated by our past. If you think about it, life-sustaining plants like kalo have never stopped growing since their original cultivation. Passed between hands and generations, islands and eras, the regenerative rhizome of kalo has kept roughly the same plant alive throughout time. The kalo in Hawaiʻi’s loʻi today carry that genealogy. It is up to us to keep plants flourishing for future generations. Thankfully, we have the knowledge and love of many ancestors to keep us growing.

People need plants. Plants need you.

Plants nourish our ecosystems and communities in countless ways. When we care for plants, they continue caring for us. Help us grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants.

From Cliffhanger to Cultivation

Rare plant cutting collected by drone has rooted, flowered, and seeded

By David Bryant, Director of Communications

What came into focus on the emerald peak of Mauna Pulou astounded our team. The drone relayed footage of an incredibly precious plant. There, backdropped by Limahuli waterfall and nestled amongst a tapestry of other cliff-dwelling plants, grew laukahi (Plantago princeps var. anomala). A healing herb in Hawaiian medicinal practice, this cherished species has supported wildlife and people for generations. The critically endangered anomala variety is found only on Kauaʻi. Before this fateful flight in 2017, it was thought that less than 25 existed.

(L) Laukahi (Plantago princeps var. anomala). (R) Laukahi on Mauna Pulou as seen by drone

Lei Wann, director of Limahuli Garden and Preserve, shares “Laukahi can be interpreted as either ‘singular leaf’ or many ‘singular leaves’. If you think about how remote and exceptionally rare this variety of laukahi is, it adds more metaphorical meaning to the few individuals remaining.”

The images taken that day in Limahuli Valley revealed a new population. They had persisted in the refuge of these storied cliffs, above the fray of development and pressures of invasive species. That was the first time a drone had been used to discover rare plants in the Pacific, led by Ben Nyberg (GIS and drone program coordinator). While this was a seminal step, our journey to safeguard laukahi had just begun.

To help perpetuate this critically endangered species, our next objective was to bring laukahi into cultivation. But retrieving seeds and cuttings by rappelling methods would be dangerous if not impossible. Once again, we turned to drones. Our drone program worked with engineers at Outreach Robotics and researchers from the University of Sherbrooke to design the Mamba. This drone-based tool is equipped with a robotic arm that can safely collect plants once perilously out of reach. The Mamba has revolutionized our collecting methods. We can now remotely collect plant cuttings from otherwise inaccessible cliffs and dramatically reduce the transit time of fragile plant material back to our nursery.

The Mamba ascends to the peaks of Limahuli Valley

In 2022, our teams returned for a flight to Mauna Pulou, this time with the Mamba. Where we could once only look at these exceedingly rare plants, we could now reach out and bring hope home. That day, the Mamba’s arm grasped the woody stem of a laukahi and delicately removed a cutting. The team was elated. We could now attempt to grow a brighter future for this plant in our Conservation Nursery.

“It’s been amazing to see the laukahi story come full circle. When we found the plants in 2017, we thought they were impossible to access. Now only five years later, we have those exact individuals growing in our nursery. It highlights just how far the technology has progressed” shares Ben.

(L) Lei Wann holding the freshly picked laukahi cutting. (R) Rhian Campbell with the rooted laukahi in our propagation lab

For nursery manager Rhian Campbell, “Protecting rare plants is both a challenge and responsibility.” Growing and caring for irreplaceable plants like the laukahi requires a deep understanding of their growing conditions and needs, which can often start off as a mystery. For Rhian, caring for these plants translates to caring for the ʻāina (land). “I view plants as integral members of a larger community that we are all a part of. I know deep down that we depend on healthy connections between all members of that community in order to survive.”

Once the laukahi cutting collected by the Mamba made its way to Rhian, the challenge before her and the nursery team was to successfully root the plant. Laukahi are notoriously difficult to root. The nursery team used a mixture of educated guesswork, a new propagation technique, and kept the cutting in a climate-controlled lab. All the investment and passion paid off: the laukahi rooted!

Soon after, hope not only took root – it flowered and seeded! The Mamba-collected plant developed several flowering heads and when we gently shook each to release pollen, seeds fell into the container underneath the plant. Several of these seeds have germinated and are surviving in our nursery. Rhian was also able to provide our Seed Bank with approximately 500 seeds for safekeeping.

Rhian Campbell collecting seeds from the flowering laukahi plant

Laukahi seeds

At NTBG, we’ve been known to go to great lengths for plants. From rappelling down the world’s tallest sea cliffs to using drones to collect once-inaccessible species, we are passionate about plant conservation. Why? When we care for plants, we care for our ecosystems and communities. One day, we hope to restore populations of laukahi plants in their natural habitats and keep cultural connections to this revered species alive. The flowering plant in our nursery has given us more than 500 reasons to be hopeful.

People need plants. Plants need you.

Plants nourish our ecosystems and communities in countless ways. When we care for plants, they continue caring for us. Help us grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants.

.svg)