By Jon Letman, Editor

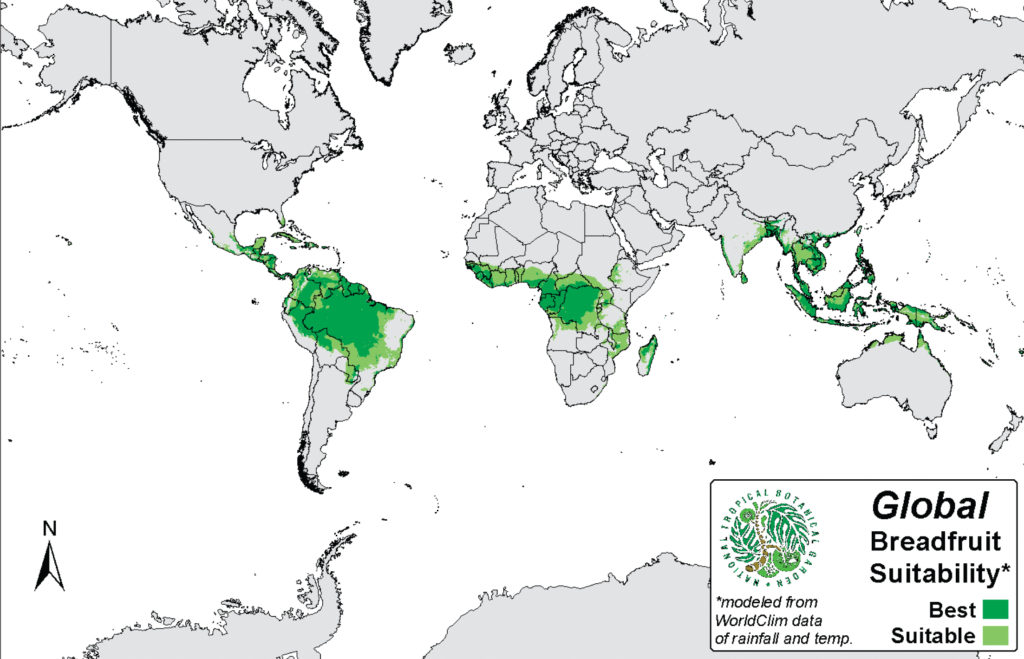

Posted on a wall in the office of the Breadfruit Institute at National Tropical Botanical Garden headquarters, a world map is marked by a bright green band indicating where breadfruit grows best. That band represents the potential to improve food security, increase reforestation, and bolster economic self-sufficiency.

One of the Breadfruit Institute’s most successful partnerships is with the Trees That Feed Foundation (“Trees That Feed”). Co-founded in 2008 by wife and husband Mary and Mike McLaughlin, two Jamaican-born breadfruit enthusiasts, Trees That Feed was established as a non-profit organization with the encouragement and support of NTBG Trustee Emeritus Douglas McBryde Kinney who also introduced Mary and Mike to Dr. Diane Ragone, director of the Breadfruit Institute.

Mike and Mary wanted to do something about climate change, environmental degradation, and global hunger, while creating economic opportunities. With breadfruit, they found they could address all.

As Trees That Feed grew, two promising breadfruit varieties—the Samoan Maʻafala and Tahitian Otea—caught Mary and Mike’s attention. After years of collaboration between Diane Ragone and Dr. Susan Murch, a plant chemist and tissue culture researcher at the University of British Columbia – Okanagan, Maʻafala and Otea were identified for their vigor, nutritional value, and suitability for mass micropropagation and global distribution.

Diane, who has spent more than 30 years studying and collecting breadfruit varieties from 50 Pacific islands, built the largest, most diverse collection of breadfruit varieties in the world. Since establishing a partnership with the Breadfruit Institute, Trees That Feed has distributed tens of thousands of micropropagated breadfruit trees originating from NTBG’s conservation collection to at least 18 countries and territories.

Since 2018, Trees That Feed has purchased breadfruit treelets from Tissue Grown, a California-based plant tissue culture company which grows the Breadfruit Institute-sourced Maʻafala that Mary and Mike have mostly donated to growers in Central America, the Caribbean, and Africa. A portion of the trees are sold commercially which helps support NTBG and the countries of origin.

Tissue Grown’s president Carolyn Sluis explains how the tissue culture-raised breadfruit treelets are grown in peat and vermiculite plugs without soil. After acclimatizing in the greenhouse for six weeks, they are distributed around the world in flats of 72 saplings. Before the plants can be shipped, Tissue Grown must complete complicated and time-consuming shipping protocols through their local agriculture department. Once approved, the trees are sent by air and hand-delivered to overseas destinations by operations manager Karin Bolczyk.

Despite two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, Tissue Grown grew more than 100,000 Maʻafala and Otea in 2020-21. Last December, they shipped 1,800 Otea to Kenya with another shipment of three flats to Guinea in January 2022.

Calling Diane Ragone’s enthusiasm “infectious,” Carolyn hopes breadfruit will gain a foothold in more countries. For a company more accustomed to growing walnuts, pistachios, and cherries, breadfruit is somewhat unusual, but Carolyn and Karin agree that Maʻafala and Otea, with their “South Pacific vibe,” make breadfruit an irresistible feel-good crop.

One of the farmers Karin has delivered breadfruit to was Nate Olive, owner of the 130-acre Ridge to Reef farm on St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands. In the aftermath of the category-5 Hurricane Maria which devastated the region in 2017, Nate shifted his focus to growing breadfruit to replace lost trees and which he says proved to be a great morale booster.

Coordinating with Trees That Feed and Tissue Grown, Nate has already distributed some 3,500 donated trees on St. Croix, St. Thomas, and St. John. In addition to local Caribbean White and Yellow varieties, Nate grows Ma’afala which he distributes to farms, home owners, and government properties in order to improve food security and local economic development.

Breadfruit was introduced to the Caribbean in the 1790s and has long been used in traditional dishes like callaloo, tostones, and monfongo. Although breadfruit is considered a local crop, Nate says, “We’re very respectful of the food and its identity…we feel connected with our brothers and sisters in the Pacific.”

Five hundred miles southeast of St. Croix, on the island nation of Barbados, breadfruit is eaten with flying fish as a mash called coucou. Barney Gibbs, chairman for the Future Centre Trust, one of Barbados’s oldest environmental NGOs partners with Trees That Feed to provide for urban reforestation. Barney says importing breadfruit has allowed him to introduce greater horticultural variety to the island.

Since 2015, Barney has received three shipments of around one thousand Ma’afala which, he says, has proven to be popular for its compact, easy-to-manage. He adds that the pandemic has only made breadfruit more popular as a nutritious, reliable crop, and for use in value-added products like flour, chips, and other foods.

Barney’s main project is urban reforestation along a nineteenth-century railway line that was converted into a biking and walking trail. The Barbados Trailway project is being lined with breadfruit and other fruit-bearing trees, providing food for anyone who needs it. Other trees are given to local schools and community centers.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, Catholic nuns in Kenya are harvesting what they call in Swahili shelisheli (breadfruit). Unlike in the Caribbean, breadfruit is a recent introduction. Joseph Matara, founder and executive director of the non-profit Grace Project (and Trees That Feed board member) welcomes the new crop. Joseph works closely with Mary and Mike to ship Otea and Ma’afala trees to Mombasa, Kenya, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and Uganda’s Jinja district, north of Lake Victoria.

Like a handful of breadfruit trees believed to have been imported to Zanzibar from Goa long ago, breadfruit is proving to be best suited along East Africa’s coastal regions. Joseph has coordinated the donation of young trees to schools and other places where they are most needed. The high nutritional value and versatility of breadfruit make it ideal for improving food security. “For some of these children,” Joseph says, “what they eat at school is their only meal for the day.”

Other projects in West Africa (Ghana and Liberia) are taking root and Joseph sees great potential for breadfruit in Mozambique too.

At its core, the Trees That Feed Foundation is about helping people. Mary recalls shipping one thousand breadfruit trees to Haiti in July 2021. Those trees arrived less than 24 hours before Haiti’s president was assassinated, an event that led to great instability. One month later, Haiti was rocked by a 7.2 earthquake and powerful tropical storm which soaked the nation already upended by political violence, poverty, and COVID.

Mary says that after last summer’s earthquake, trees they had imported in 2012 proved to be a lifesaver when other food sources were cut off. “The work of NTBG helped us get established to where we could feed thousands of people in the area immediately around the epicenter of the earthquake.”

Mike adds the network between the Breadfruit Institute, Trees That Feed, and other partners is a testament to the power of breadfruit. “We are ecstatic about being able to collaborate with NTBG. We couldn’t do what we’ve done if they hadn’t helped us so much.”

Mary too says she’s grateful for the partnership. “If breadfruit can be the source of a job, an environmental benefit, and feed the world’s poorest people, then I think we’ve done a pretty damn good job.”