By Brendan Stogner, Mālama ʻĀina Technician II

The nettle family, Urticaceae, encompasses a diverse group of plants known for their stinging leaves and rich historical importance. Found worldwide, from temperate to tropical forests, nettles have been integral to human societies for millennia. Beyond their notorious sting, nettles have served as a source of food, medicine, and fiber, weaving themselves into the fabric of many civilizations. In Europe, species like Urtica dioica have been utilized for textiles, their strong fibers yielding durable fabrics worn by ancient warriors and modern fashionistas alike. Across Asia, varieties such as Boehmeria nivea have been cultivated for their silky fibers, used in traditional garments and papermaking.

Amidst this global tapestry of nettle use, Hawaiʻi boasts several unique members of the nettle family, including olonā (Touchardia latifolia). Olonā is revered for its robust fibers, which have supported Hawaiian culture for centuries. From this endemic Hawaiian plant comes one of, if not the strongest and most versatile plant fiber cordages in the world. Cordage made from olonā has a wide array of uses, most notably as fishing line, nets, and various bindings. The relationship between olonā and Hawaiian people embodies not only practical utility but also profound cultural and spiritual significance.

Historically, the process of harvesting and preparing olonā fibers was considered a sacred and specialized skill. It involved careful selection of the plant, stripping the bark to extract the fibers, and then twisting and braiding them into strong cords. Skilled practitioners of this art were highly respected in Hawaiian society. Olonā and the art of cordage-making are deeply embedded in Hawaiian traditions and identity. The knowledge of olonā cultivation and fiber preparation was passed down through generations, ensuring the preservation of cultural practices and the sustainability of natural resources. To care for these plants meant to care for the community.

Just $25 powers a year of impact for plants and people no matter where you live. You’ll also receive The Bulletin magazine and invitations to special member events.

Join usHistorically, olonā has faced pressure from feral ungulates and over harvesting and continues to dwindle in the wild. A parallel decline can be observed in the perpetuation of traditional practices and cultural knowledge. With each diminishing olonā plant, so too wanes the expertise passed down through generations: the knowledge of when and how to gather the plant, the methods to extract its fibers, and the intricate art of weaving them into cordage. This decline not only threatens the biodiversity of Hawaiʻi’s native flora but also erodes a vital link to Hawaiʻi’s cultural heritage. As elders who possess specialized knowledge of olonā grow fewer in number, their traditions and stories that connect olonā to the daily lives and spiritual practices of Hawaiian communities are at risk of fading away.

This issue hasn’t gone unnoticed here at Limahuli Garden and Preserve. Our responsibilities in the valley extend beyond the conservation of native Hawaiian plants to include the perpetuation of Hawaiʻi’s cultural heritage. In 2022, plans to cultivate a new site dedicated to olonā within the garden were established, spearheaded by Mike Demotta, NTBG’s now-retired living collections curator, who had witnessed firsthand the diminishing populations of olonā.

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, Mike envisioned a specific site for the cultivation, care, and sustainable harvest of olonā, ensuring the perpetuation of both the plant and its cultural practices. Limahuli Garden and Preserve director, Lei Wann, along with horticulture specialist, Randy Umetsu, joined Mike in scouting potential sites within the garden to bring this idea to fruition.

In the wild, olonā typically thrives in very wet, shady areas along streams, often under a heavy tree canopy or in dark gulches. When selecting an ideal site for cultivating olonā, several critical questions arose: Is the site sufficiently wet? Is it cool? If not, can these conditions be artificially created? After careful consideration, staff decided on a triangular, one-acre area of Limahuli Garden previously called the “Invasive Forest Walk” nestled between two ephemeral streams. At the time it was overgrown with invasive plants, but the team recognized its potential.

Shortly after the site was chosen, I started working as a horticulture technician in the garden. Having read accounts of olonā cordage being preferred by mountain climbers and ship captains, I was fascinated that one of the world’s strongest plant fibers was endemic to Hawaiʻi.

While fully committed to the project, we recognized the daunting task before us. With support from local arborists, we began systematically clearing invasive mango, octopus trees (Schefflera actinophylla), and banyans. But as the dense canopy receded, sunlight reached the forest floor, awakening a deluge of weeds. Undeterred, we diligently weeded, mulched, and left felled trees to decay, fostering a habitat for native fungi to break down the debris.

Our efforts revealed promising signs: māmaki (Pipturus albidus) seedlings, another native nettle renowned for making tea and cloth began to emerge as though the valley itself supported our work. After welcoming school groups and hosting community and volunteer days to prepare the site, we organized a staff planting day in August 2022, introducing hundreds of native Hawaiian plants including some 40 olonā.

As we worked, we recited Pule Hoʻoulu, a Hawaiian oli (chant) that invokes rain and new growth, while Hawaiian practitioners blessed the space. Once the site was planted and new irrigation installed, all we could do was wait and watch as māmaki seedlings formed a sheltering canopy over the young olonā plants. Under the protective shade, the olonā thrived, transforming the once invasive forest walk into a fully functional native Hawaiian agroforest.

Two years later, the site is healthy and growing with nearly 50 robust olonā and thousands of other culturally significant plants. For Limahuli’s horticulture staff, a major focus has been collecting specimens from as many of Kauaʻi’s olonā populations as possible to ensure diverse genetic representation in the new site.

Currently, we have olonā from six areas, each displaying distinct morphological characteristics. Additionally, we’re reaching out to more experienced growers to enhance our knowledge of this notoriously difficult-to-grow plant.

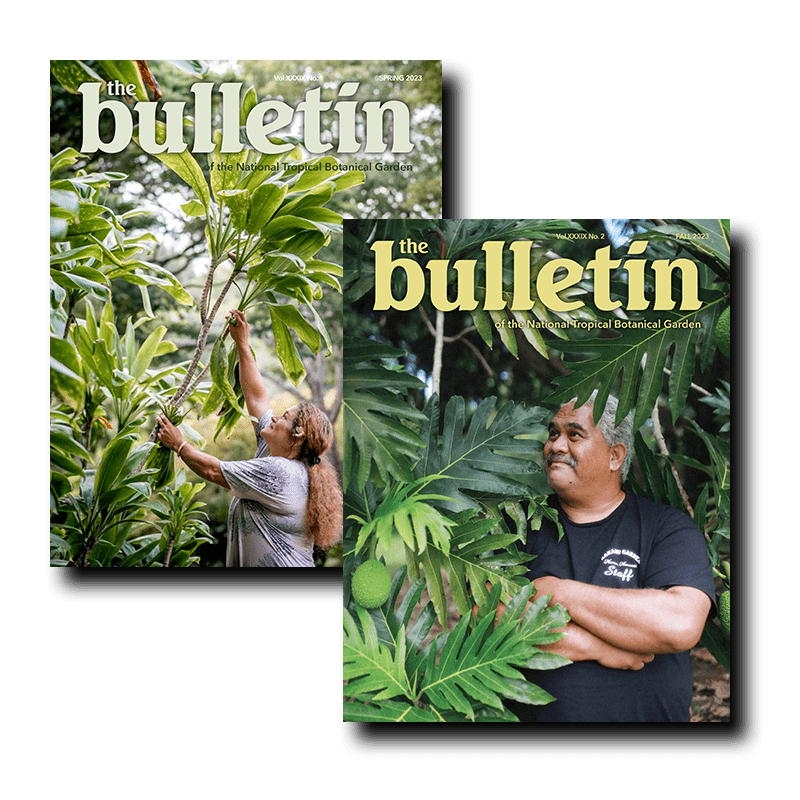

Limahuli Garden and Preserve director Lei Wann strips bark from olonā plants on the North Shore of Kauaʻi. Photo by Ezikio Quintana.

In the future, I envision thousands of thriving olonā, creating a space where cultural practitioners can regularly harvest and learn about this incredible plant. Rather than a rigid “look but don’t touch” approach, this can be a place to foster a deeper relationship for this community and the land.

Personally, I feel deeply connected to this site because my journey at Limahuli began alongside the olonā plantings and in this valley we’ve grown together. Our efforts go beyond saving one plant species; we aim to safeguard an essential aspect of Hawaiian identity, perpetuating the centuries-old connections between people and plants.

By revitalizing the cultivation and sustainable management of olonā, we aspire to ensure that future generations inherit not only its physical resources but also the invaluable cultural legacy it represents.