An Eye On Plants: Pogostemon guamensis

By Jon Letman

Inherent in the notion of discovery is a sense of immediacy, but the truth is, quite often a plant unknown to science may be first collected many years before it is identified, recognized, and published as a “new species.” Take the Pogostemon guamensis, for instance.

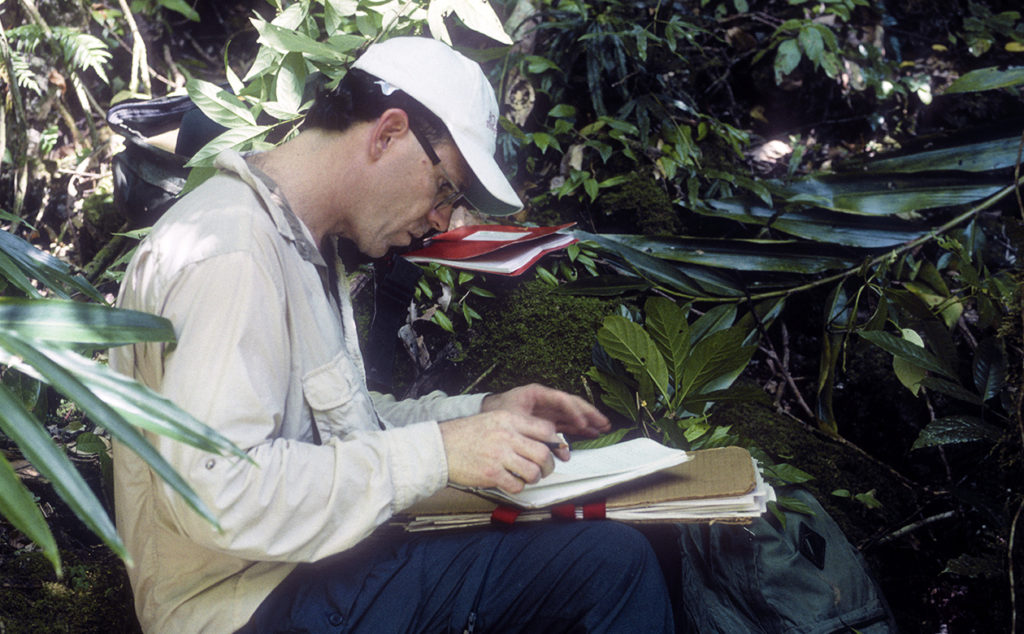

First collected by botanist Derral Herbst on Guam in 1982, a second round of collections was made by NTBG botanists Steve Perlman and Ken Wood twelve years later while conducting a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service-funded survey of the karstic limestone cliffs on Guam’s northeastern tip.

Known for their rappelling and cliff collecting skills, Steve and Ken were commissioned to spend part of spring and summer 1994 suspended by ropes exploring Guam’s jagged high cliff habitat. Steve recalls working in the blinding July heat, buzzed by Mariana crows and soaring fruit bats as they documented the then unidentified member of the Lamiaceae (mint family) in five separate sub-populations.

Upon their return to NTBG, senior research botanist Dr. David Lorence suspected the plant belonged to Position, a genus of nearly 80 accepted species with high diversity in the Indian subcontinent, but then unknown from Micronesia or other Pacific Islands. At the request of NTBG research associate Dr. Warren Wagner, a specimen was sent for DNA analysis to the Smithsonian Institution where Warren also commissioned scientific illustrator Alice Tangerini to do a line drawing.

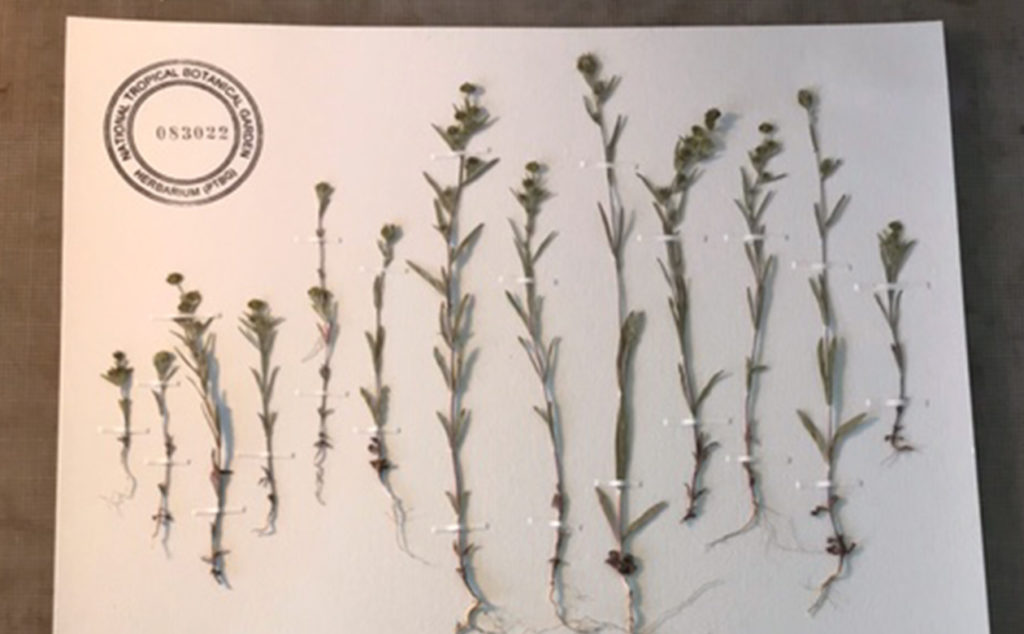

The species holotype (representative specimen) collected by Steve and Ken is curated in the type cabinet at NTBG’s herbarium with its duplicates (called isotypes) shared with six other institutions including the University of Guam, the Bishop Museum in Honolulu, and the U.S. National Herbarium at the Smithsonian Institution.

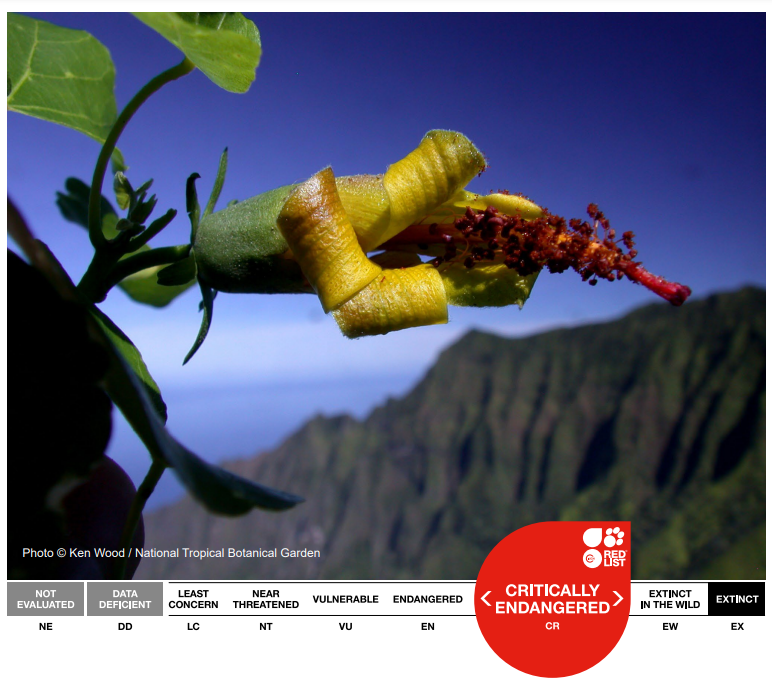

Because of the low number of individuals (113 recorded) and its very restricted range, the species was given a preliminary IUCN assessment of Critically Endangered. The plant grows only on cliffs surrounding Andersen Air Force Base and is isolated from people, but it is thought to be threatened by invasive species, typhoons, and possibly animals such as feral pigs and deer.

Using molecular and morphological data, David Lorence, Warren Wagner, and collaborators determined the plant was in the genus Pogostemon (meaning ‘bearded stamen’) and appropriately named the species for its home island. Interestingly, unlike its relative Pogostemon cablin (patchouli) which is well-known for its pungent, musky smell, P. guamensis is scentless, like other Lamaiaceae found in Hawaiʻi.

Finally, in December 2020 Pogostemon guamensis was published in the peer-reviewed open access journal PhytoKeys. Some might ask, why did it take so long?

In the words of Dave Lorence, “The wheels of taxonomy grind slowly but very finely.” Ironically, Steve points out that not all undescribed species are published so fast. This species, like many others, was a side project, and among the 500-1,000 species across the Pacific that NTBG scientists are studying at any given time. With stretched resources and a limited number of classically trained taxonomists and experts available, publication can take years.

Pogostemon guamenis is another example of the importance of conducting field work in remote and under-studied areas, says Dave. “There are still plants out there that we hadn’t known existed until the survey work was done. It’s really important to study and name the plants before they go extinct.”

Presently, there are no known P. guamensis in cultivation and so conserving the species would require returning to its known locations to collect seeds and/or cuttings. Ken says, “Having the publication will make more people aware that this species exists and hopefully they will start conserving it.”

Figs, wasps, and fidelity

By Jared Bernard

If you were a botanist, you might think NTBG’s garden sites on Kauai are valuable because they allow for the study of Hawaiian and Polynesian plants. But NTBG also houses a multitude of plants from around the world, both living in the gardens and preserved in the herbarium. Having so many plants within reach presents a rare opportunity to delve into their stories.

Kelsey Brock, a research associate at NTBG, learned this when she spotted a fig sapling growing in the crotch of a Java plum tree in 2017. The sapling turned out to be a Watkins’ fig (Ficus watkinsiana), a non-native species not known to reproduce on Kauaʻi. Kelsey focuses on non-native plants that establish wild populations (called naturalization), especially those that could imperil Hawaiian ecosystems.

For three years, Kelsey scoured the island as a botanist with the Kauaʻi Invasive Species Committee, using NTBG’s herbarium as a reference collection and to deposit vouchers of recently introduced non-native species. She was accustomed to coming across new things, but when she encountered the wild fig, she knew something was weird.

Figs are notorious for having unique pollinator wasp requirements. Generally, plants that can establish themselves in a new environment are receptive to whatever pollinators are present. But figs and their pollinators have a special relationship based on absolute fidelity or “mutualism” in which they’re totally obligated to each other.

Viewing a fig tree’s flowers requires a microscope. The flowers are minuscule and hidden inside what is typically referred to as a “fig.” Pollination requires each fig species to release its own unique scent to lure its exclusive tiny pollinator wasp. The wasp must then navigate through a pinprick-sized portal on the fig, aided by its specialized head shape, to reach the flowers inside. The wasp’s goal is to put an egg in every flower so its young can get nourishment from the fig ovules. These flowers do not develop seeds, but instead tiny wasps. Some of a fig’s flower stalks are too tall, and as the wasp struggles, they get pollinated. Those flowers develop seeds that eventually become new fig trees. The fig-wasp relationship is one of absolute dependency.

Kelsey knew there were only two explanations for figs growing in the wild. Either “the fig wasp pollinators have arrived,” she said, “or the mutualism isn’t as obligate as popularly thought.” Were the figs finding new pollinators?

Solving this mystery required a closer look at the dozens of fig species on Kauaʻi. The first step was to collect figs from as many of these species as possible, whether cultivated or wild. Fortunately, NTBG’s gardens have representatives of almost all of these figs.

“NTBG’s living collection, with at least 41 mature fig species in close proximity in the Lawaʻi Valley, provided a perfect test tube to investigate these relationships,” Kelsey said. Specifically, the “living collection” includes a cornucopia of fig species in McBryde Garden, a few growing next to the Botanical Research Center, and the immense Moreton Bay fig trees (Ficus macrophylla) in Allerton Garden.

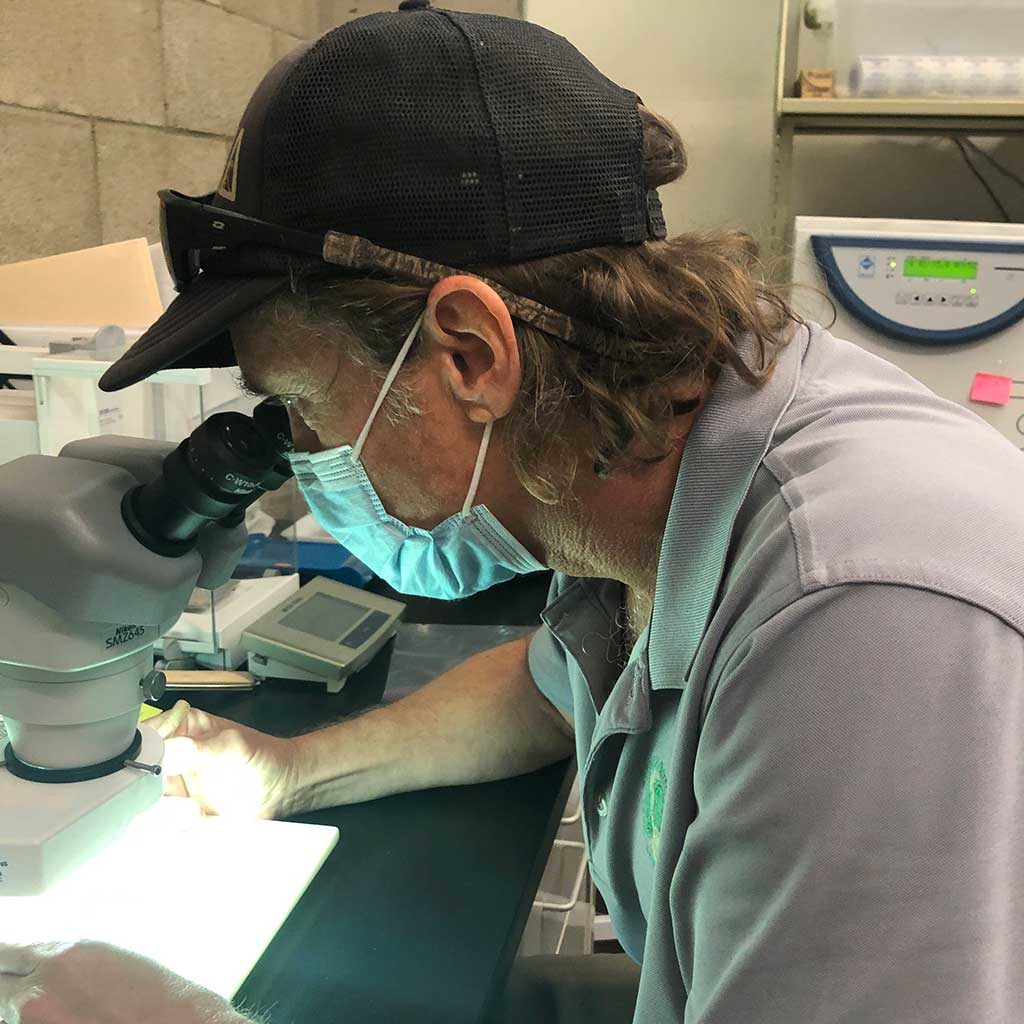

My role, as an entomologist with the University of Hawaiʻi–Mānoa, was to dissect the figs under a microscope to identify any wasps I found and collect any seeds. Most of the figs had nothing in them. But some fig species were astonishing, and every time I opened a fig, unknown things poured out. Several wasp species were not previously known to be in the Hawaiian archipelago. Emerging wasps meant they were reproducing, but what about the figs?

For the interaction to be mutual, the figs also needed to be pollinated and produce seeds. This part of the investigation required NTBG’s seed laboratory managed by Dustin Wolkis. Along with NTBG’s conservation biologist Seana Walsh, Dustin took the seeds I found and used a hi-tech germination chamber to see if they were viable. Dustin and Seana watched carefully for the seeds to sprout.

We also wanted to know whether figs were naturalizing. This was largely based on Kelsey’s island-wide surveys, but to finalize our fig collection Tim Flynn, NTBG’s herbarium curator, guided us deep into the Līhuʻe-Kōloa Forest Reserve. Tim knew a shortcut into the reserve using a trail behind his house which led us to an old road leading into the Wahiawā Mountains where we found that the Moreton Bay fig and Port Jackson fig (Ficus rubiginosa), both introduced for forestry a century ago, were starting to naturalize.

Dustin exclaimed that the fig seeds were “very much alive!” He and Seana found that all the fig species containing pollinators had sprouted little seedlings, each capable of growing into a new tree, meaning the wasps were indeed pollinating them.

Don’t forget about that initial Watkins’ fig. It too may be in an early stage of naturalizing. But while the other naturalizing figs were pollinated by their normal specific wasps, we caught the Watkins’ fig in a relationship with the pollinator of the Port Jackson fig. Both fig species are closely related and live together in their native range in Australia. No one ever found this wasp using the Watkins’ fig before, which may mean that it can’t compete with the Watkins’ fig’s normal pollinator. On Kauaʻi, however, the Port Jackson wasp (Pleistodontes imperialis) doesn’t need to contend with anyone.

We were shocked to find the Port Jackson wasp also interacting with another fig species that isn’t closely related at all: the red affouche (Ficus rubra), native to islands near Madagascar. This was among the trees we surveyed at McBryde Garden. The red affouche isn’t yet naturalizing, but with baby wasps and viable seeds, it has all the necessary ingredients. It could be only a matter of time.

To be sure these figs are sharing a pollinator, we teamed up with George Weiblen, a botanist at the University of Minnesota–Twin Cities who has studied figs for over 25 years. His lab analyzed the DNA of wasps and figs to be doubly certain of their identities.

Finding the Port Jackson wasp in the red affouche meant that it wasn’t merely hopping to close relatives. We checked other relatives of the Port Jackson fig but the wasp was absent. Something else was enabling it to interact with different fig species. By scrutinizing various fig shape dimensions, we discovered that this wasp can interact with figs whose portals have a particular shape, like a lock to which they have the key. This would be like finding out that your house key opens doors on the other side of the world.

Last November, we published our discovery in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. We concluded that the tactics species use to maintain their unique relationships, such as figs having special shapes or wasps out-competing each other, can falter outside of their native ecosystems. The diversity of figs at NTBG’s gardens helped us understand how strict mutual relationships form, and how easy it is for them to fall apart.

Jared Bernard is an entomologist PhD candidate at the University of Hawaiʻi-Mānoa.

Uala – Hawaiian Sweet Potato

By Mike DeMotta, Curator of Living Collections

“He ‘uala ka ‘ai ho’ola koke i ka wi” – Sweet potato is the food that quickly restores health after famine

The first Hawaiian voyagers arrived in the Hawaiian Islands with approximately two dozen plants that were important enough to earn space on the crowded outrigger canoes used to cross the ocean. These ‘canoe plants,’ as they are known, were vital for providing food, fiber, medicine, and more. Many of these plants had multiple uses. Three were essential staple food crops — kalo (taro), ulu (breadfruit), and uala (Hawaiian sweet potato).

Easily propagated and grown from live cuttings or slips, uala (Ipomoea batatas) was widely cultivated on all the islands. Many communities in Hawaii’s driest areas placed great value on uala and were able to produce enough of the starchy vegetable to sustain large populations by strategically planting it during the rainy winter months and keeping it stored underground for some time after the rains had ended.

Over many generations, mahiai (Hawaiian farmers), who understood the importance of crop diversity, developed many different varieties. They cultivated these hearty, tuberous roots, protecting against total loss of any given variety and building resilience in the event of changing weather patterns or other environmental instability.

As a staple food, uala is an excellent source of vitamin C, beta carotene, potassium, protein, and minerals. The unevenly-shaped Hawaiian sweet potato is valued as a life-preserving crop, but the shoots and young leaves (called palula in Hawaiian), are also cooked and eaten. Offering great flexibility in its preparation, uala can be cooked in the same ways as other potatoes. My favorite way to enjoy uala is steamed in an imu (traditional Hawaiian underground oven). Like kalo, uala can also be mashed into a soft poi which has the consistency of thick pudding and is eaten with fish. Uala poi ferments quickly and so it must be consumed within a day or two. Grated uala cooked with coconut milk is called palau and enjoyed as a special treat.

Today there are about 24 different varieties of Hawaiian uala. Each has a distinctive leaf shape and colors of skin and flesh that range from orange and red to white. The variety Eleele literally means ‘black’ and is named for its very dark stems. Huamoa (‘chicken egg’) is a smallish, egg-shaped tuber. Inside, its darker yellow center is reminiscent of an egg yolk. Palaai (literally: ‘fat’) refers to the size of the large tubers. Piko (‘navel’) is recognized by its deeply-lobed leaves.

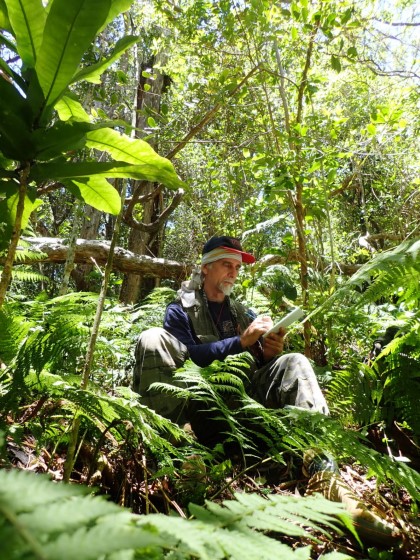

Mike DeMotta Inspects uala variety papaa kowahi growing outside the nursery.

Like other multi-use edible canoe plants, many uala have medicinal value. One example of uala’s medicinal use was in the concoction apu, a drink with many ingredients, but primarily made with uala. Apu has been traditionally prepared for women to be taken soon after childbirth to facilitate healing.

NTBG currently has about 20 uala varieties in our collections growing at our south shore Conservation and Horticulture Center and at Limahuli Garden on Kauai’s north shore and Kahanu Garden on Maui. We maintain all varieties within our nursery because of the challenges of growing uala in the field, namely the tenacious feral pigs who always seem to know when uala is ready to harvest. If we don’t get to them first, the pigs will complete their own harvest and never fail to eat everything, destroying all stems and leaves as they go. Growing a backup collection safely inside our nursery, helps us ensure we preserve these irreplaceable varieties.

At NTBG, we have a strategic objective to maintain collections of important Hawaiian canoe plants within our gardens. Heirloom or heritage varieties of canoe plants that are not grown commercially tend to become less common. Each named variety of canoe plant holds great importance in Hawaiian culture, whether identified in ancient legends or for its value as food and medicine. Preserving these varieties, cultivated over many generations, and the names ascribed to each, is equally important. As a key component of Hawaiian language and culture, we must remember these names which provide connections to Hawaii’s ancestors. The same uala we grow today can be traced back many generations to Hawaiian farmers of long ago, providing us with essential sources of food, medicine, and beauty, and living links to an ancient past.

The UN General Assembly has designated 2021 as the International Year of Fruits and Vegetables. The campaign provides an opportunity to increase awareness of the importance of fruits and vegetables to health, nutrition, food security, and UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Turning the Tide on Climate Change: Sea Water, Salinity and Coastal Plants

Coastal plants may provide some of our best defenses against the impacts of climate change. However, rising sea levels, shifts in rainfall and storm surge are taking a toll on native coastal ecosystems in Hawaii. To better understand how rising sea levels may affect native and non-native plant life, NTBG scientists and collaborators are studying the effects of increased seawater exposure on seed germination and plant development. When you support National Tropical Botanical Garden with a gift to the Growing Green campaign, you help fund critical research and new knowledge that prioritizes restoration efforts to save both plants and people.

Hawaii is well-known for its picturesque beaches and dramatic seaside cliffs, but there are more than just stunning views to discover along the tradewind-swept coastlines of this tropical archipelago. Tucked into jagged volcanic rocks and snaking along sandy dunes is a world of coastal beauty elegant in form and critical in function.

Thick creeping ground covers and shrubs provide habitat for nesting seabirds, stabilize sandy soil and mitigate erosion. Many of the colorful, diminutive flowers found along Hawaiian coastlines provide food for insects and birds and are used in cultural ceremonies and lei making. Unfortunately, few Hawaiian native coastal plant communities remain intact in the wild. As sea levels rise, so too does the salinity level of the sandy dune environments many of these important plants call home. Whether or not Hawaii’s coastal plants can tolerate this change in salinity remains largely unexplored, but a team of NTBG scientists and collaborators is on a mission to learn more.

“Native dune plants are often thought to be salt-tolerant due to their proximity and exposure to the ocean,”

Kasey Barton, PhD., Principle Investigator and Associate Professor at UH Manoa

“Native dune plants are often thought to be salt-tolerant due to their proximity and exposure to the ocean,” says Kasey Barton, PhD., Associate Professor in the School of Life Sciences at UH Manoa and Principal Investigator on the project. “But, like most plant life, dune plants rely on fresh water for growth and development and their tolerance of elevated salinity is uncertain,” she continued.

Initial experiments have shown that seeds and seedlings are particularly vulnerable to increased salinity, which could result in population bottleneck or decline if seedlings are unable to regenerate. As the study continues, Barton alongside NTBG Seed Bank and Laboratory Manager Dustin Wolkis, NTBG Conservation Biologist, Seana Walsh and researcher Raffaela Abbriano, PhD., intend to investigate salinity tolerance across a diversity of native and invasive dune plants in order to identify salt-tolerant species that may be useful in coastal restoration efforts and vulnerable species that will require careful conservation management.

“In order to better understand the salinity tolerance of coastal plants, we need to know how salinity affects seed germination.”

Raffaela Abbriano, PhD.

“In order to better understand the salinity tolerance of coastal plants, we need to know how salinity affects seed germination,” says Dr. Abbriano. “To do this, we have designed an experiment that tests germination success and timing to germination in seeds exposed to a range of seawater concentrations,” she continued.

For seeds that fail to germinate after exposure to seawater, a secondary trial is conducted to explore how seeds recover after exposure. “Studying seed germination in this way will give us information about whether or not seeds can survive temporary salt stress in their natural environment,” she described.

Up to this point, the majority of the salinity study experimentation in Hawaii has been conducted in controlled environments inside the NTBG Seed Bank and Laboratory as well as greenhouses at University of Hawaii at Manoa. A third and vital step in furthering our understanding of how salinity affects coastal plant germination and development is to conduct experiments in the plant’s natural habitat, to see how response to increased salinity might differ in nature in an uncontrolled environment.

“We’re looking forward to beginning salinity tolerance field trials at Lawai Kai special conservation subzone in Summer 2021,” says Wolkis.

Studying the salinity tolerance of coastal plants is an important step in furthering our understanding of how the consequences of climate change will affect coastal plant communities in Hawaii and other tropical regions susceptible to rising sea levels, and shifting amounts of rainfall and storm surge. Sea level is projected to increase by up to one meter in Hawaii by the year 2100, which will change and challenge the biological resources native to the Hawaiian coastline. However, increased exposure to seawater isn’t the only threat these vulnerable plant populations may face. We must continue to invest in critical plant research like this salinity study so that conservation practitioners can make informed decisions and protect the biological diversity and resources of vulnerable tropical ecosystems in Hawaii and around the globe.

Notes: The Salinity Tolerance Project is a collaboration between University of Hawaii, National Tropical Botanical Garden, and Maui Nui Botanical Garden funded through a NOAA SeaGrant to Barton

NTBG Work Highlighted by IUCN Red List

Amazing Species: Hau Kuahiwi

Hau Kuahiwi (Hibiscadelphus woodii) is perched on the edge in more ways than one, following its rediscovery in 2019 using drone technology.

This small Hawaiian tree occurs only on the island of Kauai, where it lives on cliffs. Hibiscadelphus species are closely related to Hibiscus, but their distinctive curved flowers have an abundance of nectar and do not fully open, which is thought to be an adaptation to pollination by honeycreepers.

Predation and competition by non-native animals and plants drove the population to perilously low levels, and after three of the last four known individuals perished in a rockslide in the 1990s and the final plant died in 2011, the species was thought extinct. However, intensive drone surveys by National Tropical Botanical Garden in 2019 revealed a previously unknown population of another four individuals.

Significant challenges remain – the plants are completely unreachable by humans, and although this may afford them some protection from invasive species, rockslides remain a threat. It is possible that future technology could enable drones to collect plant material in the hope of establishing an ex situ population of this Hibiscadelphus and other similarly imperilled species for their long term protection.

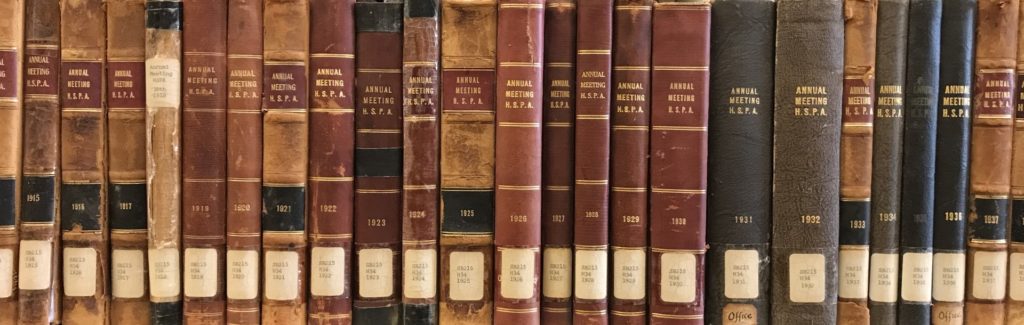

Preserved Plants Play Foundational Role in Protecting Biodiversity

Around the globe, biological scientists are racing to discover and document species before they are lost forever. The herbarium collection at National Tropical Botanical Garden contains nearly 90,000 preserved plant specimens, some dating back to 1837. It provides critical resources for biodiversity, ecological, and evolutionary research aimed at saving species. You can help us protect it. Donate to the Growing Green campaign today. Your gift will help us reach our energy efficiency goals and improve our Botanical Research Center to preserve this precious collection for generations to come.

It’s 2021 and scientists around the globe are working to document new species every day. It isn’t easy to believe in a world as connected as ours, but studies estimate that there are up to 15 million species living on Earth, only 2 million of which are known to science. This means we may share our planet, ecosystem, and maybe even our backyards with a multitude of unknown species!

At current rates, it could take centuries for scientists to discover and describe life on our planet in its entirety. Even if it is possible to do so, biodiversity is declining and disappearing at rates not seen before in human history. Botanical gardens and scientific research institutions like NTBG have an essential role to play in making a difference and stemming the tide of extinction.

“Collections of pressed, dried, and accurately identified plant specimens (herbaria) are the foundation for all studies of plant diversity and evolution,” said David Lorence, Senior Research Botanist. “Like other natural history collections, herbaria are essential resources for the classification and the study of biodiversity. If we don’t know the names of species, we can’t conserve them,” he continued.

“Collections of pressed, dried, and accurately identified plant specimens (herbaria) are the foundation for all studies of plant diversity and evolution.”

– David Lorence, NTBG Senior Research Botanist

NTBG Herbarium Collection

The Herbarium collection at NTBG includes:

- Native, cultivated, and invasive vascular plant species

- Bryophytes and lichens

- Marine algae and fungi

It is a unique reference of natural history and a resource for researchers at the National Tropical Botanical Garden and worldwide. The herbarium was established in 1971 as a record of the local flora when the Garden began operations. The collections have been built over more than 50 years through field expeditions and exchanges with other herbaria worldwide. NTBG has a very active collecting program adding 1-2 thousand new specimens per year, primarily from Hawaii and the Pacific.

As habitats disappear and our changing climate threatens all aspects of life on Earth, documenting biodiversity in herbarium collections will become increasingly important. So, how are plants entered into the permanent biological record? It starts with a discovery in the wild.

Discovering New Species

When a new plant is discovered, NTBG scientists start describing the species and preparing it for preservation in the herbarium. Scientists take field notes on the habitat and surrounding vegetation, plot GPS points and collect, press, and dry the specimens. Photographs are taken to supplement the preserved specimens, and leaf material is obtained for later molecular phylogenetic studies using DNA.

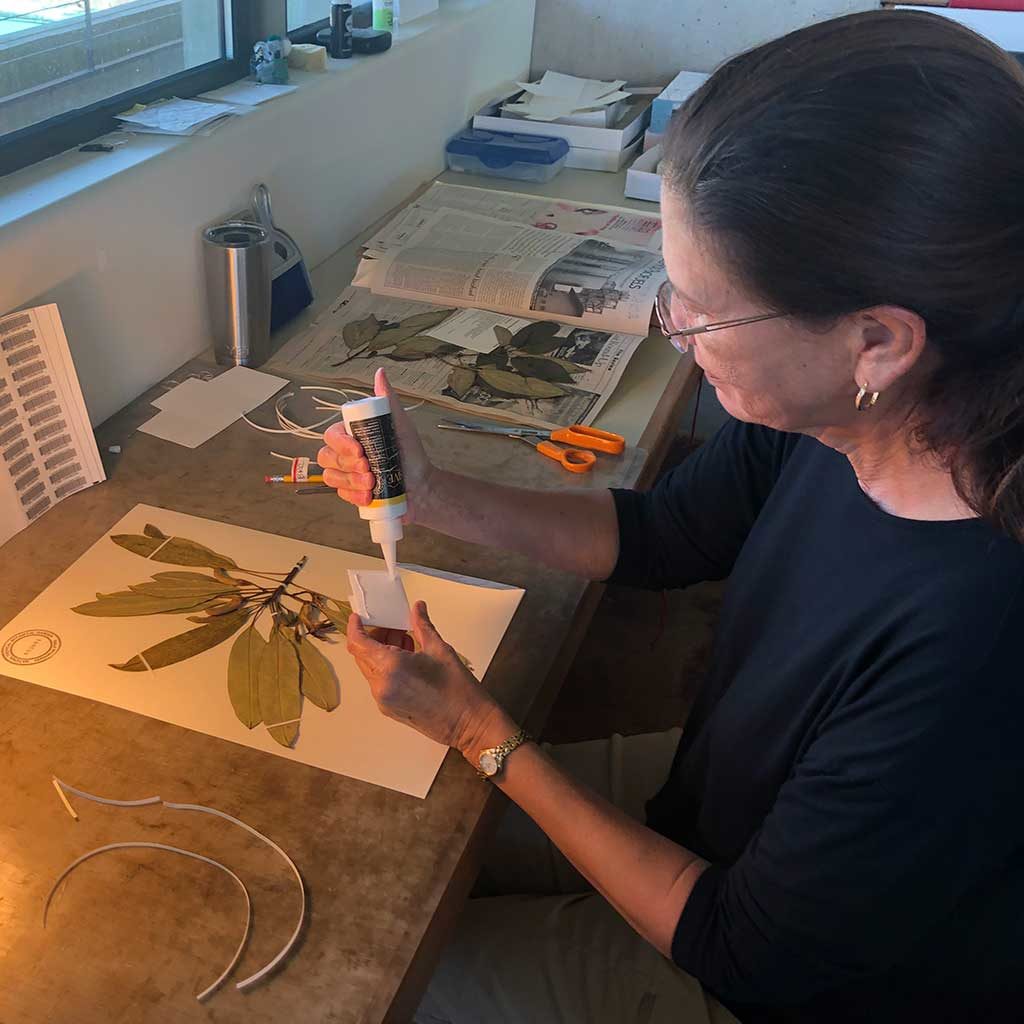

The dried specimens from the field are freeze-fumigated to remove contaminants and pests before storage. Beetles and other insects can consume and destroy herbarium specimens if they are accidentally admitted into the collection. Once the new samples have been fumigated, they are mounted on archival paper with their labels, then barcoded, imaged, and incorporated into the NTBG collection. Duplicate labeled and identified specimens are shared with herbaria of collaborating institutions, including the country of origin where the species was discovered.

Collecting Plants for Preservation Presents Challenges

Collecting plant material and entering a new species into the record is time-consuming and labor-intensive. It is often made more challenging by lack of funding, permitting, and regulations.

“Successful fieldwork requires careful planning, funding, and collaboration, especially if it takes place outside the USA,” said Lorence. “First, it is important to establish contacts and partnerships with local organizations and individuals in the host country, for these are essential for obtaining access to collecting areas and collecting permits. Training and capacity building of host country partners is also an important aspect of fieldwork. We learn as much from them as they do from us,” he remarked.

Proper equipment is also an essential part of plant discovery and documentation. Native vegetation has disappeared from most lowland areas in the tropics, particularly on islands. Most intact native vegetation is confined to mountain slopes and summits, requiring strenuous hikes carrying collecting equipment, water, and supplies.

Flora of the Marquesas

Exploring and documenting the plant life of poorly known areas with herbarium specimens and making conservation recommendations are critical steps towards producing a region’s written flora. NTBG is dedicated to tropical plant discovery, research, and conservation and recently completed the Flora of the Marquesas, a collaboration between NTBG, the Smithsonian Institution, Délégation á la Recherche de la Polynésie Française, and others that was decades in the making.

The two-volume book offers a complete account of all the plants found in the Marquesas. Of the 826 vascular plant species recorded, 331 species are native including 100 ferns and lycophytes, with the remainder being human-introduced. Nearly half of the native flora (47%) is endemic to the Marquesas.

“Knowing that specimens I’ve collected have contributed to a better understanding of the flora of a particular area is particularly gratifying.”

– Tim Flynn, NTBG Herbarium Curator

“Knowing that specimens I’ve collected have contributed to a better understanding of the flora of a particular area is particularly gratifying,” said Tim Flynn, NTBG Herbarium Curator. “The collections I’m making today aren’t necessarily for me or this time, but for future generations,” he concluded.

Herbarium Collections like NTBG’s fill in the pages of the catalog of life on Earth and can help us respond to environmental changes and threats from habitat loss and climate change. Our collection is primarily comprised of plants of the Pacific, but many other research institutions and organizations are working to document and assess species on a global scale.

A Global Catalogue of Life

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species is the world’s most comprehensive inventory of the conservation status of biological species. It helps scientists evaluate the risk of extinction for thousands of known species of plants, animals, and fungi and is an essential tool for conservation management. On March 25, 2021, the IUCN released an updated Red List which includes 134,425 assessed species from around the world. 54,127 of them are plants, each given a rank in one of nine categories from species of “least concern” to “extinct.” 28 percent of the now assessed species are recognized as “threatened”. This recent update also includes assessments of all 255 Kauai single-island endemic vascular plants completed last year in an effort led by NTBG. By completing the Red List assessments for all of Kauai’s endemic plants, NTBG has verified that 10 percent are already extinct and the remaining 90 percent all classified as “threatened” according to the internationally recognized IUCN Red List criteria highlighting the scale and urgency of plant conservation in Hawaii.

As a member of the IUCN Species Survival Commission for Hawaii, NTBG uses our Herbarium Collection data to assess the conservation status of Hawaii’s flora. Information about distribution range and population size over time determine if a species or taxon is considered a species of least concern, near threatened, threatened, endangered, or critically endangered.

Digital Resources

NTBG Herbarium staff and volunteers are currently working on digitizing the collection. As of 2021, approximately 65% of the records have been digitized and made searchable online.

NTBG completes Red List catalogue of endemic plants

NAPALI — Researchers with the National Tropical Botanical Garden were devastated when the last known wild member of the endemic flowering plant Hibiscadelphus woodii was found dead in the Kalalau Valley in 2011.

The plant only grows along the sheer cliffs of Kaua‘i and had only been discovered a few years earlier, in 1991, when new rope climbing techniques allowed for further exploration of the extremely rugged territory.

But, in 2016, the two more individual H. woodii plants were re-discovered using another new technology — drones.

Read the entire article at: https://www.thegardenisland.com/2021/04/19/hawaii-news/ntbg-completes-red-list-catalogue-of-endemic-plants/

Garden Volunteers Keep NTBG Growing Green

April 18-24 is National Volunteer Week and at NTBG volunteers are critical to our success. Despite the suspension of the volunteer program in March 2020, volunteers returned in June and 294 individuals served nearly 11,000 hours! Volunteers enhance the visitor experience by greeting guests and offering interpretation in the garden. They help maintain our facilities, care for plants in the nursery and horticulture center, clean seeds to prepare them for storage, and mount and digitize specimens in the herbarium. These dedicated folks answer our numerous calls for support and lend their time, talent, and passion to assisting NTBG staff in documenting and protecting some of the world’s rarest plant species. As a nonprofit environmental organization committed to plant conservation, we rely on volunteers to help us save plants and people. You can help. Become a volunteer today or contribute to the Growing Green Campaign to help us reach our energy efficiency goals.

Spotlight on Botanical Research Center Volunteers

No matter your skill, age or interest, you can help National Tropical Botanical Garden save plants. This week we’d like to thank and highlight some of our dedicated Botanical Research Center volunteers. Find out what they are working on and what they love about volunteering with NTBG!

“Without our volunteers, we couldn’t accomplish many of our goals – we rely on volunteer efforts to mount almost all of our specimens as well as digitize those specimens once they have been mounted. These efforts help make our specimens available and useful to a world-wide audience. We simply couldn’t perform very necessary functions in a timely manner without volunteer help.”

– Tim Flynn, Curator of the Herbarium

Herbarium Specimen Mounting

Herbarium Specimen Mounting volunteers use their artistic eye to mount pressed and dried plant materials collected from the field onto paper for storage in the Herbarium. Sometimes this task can be quite challenging! Volunteer Joan Shaw had her work cut out for her carefully mounting this tiny challenge.

Joan Shaw, Volunteering Since 2019

What brought you to NTBG and the Botanical Research Center?

I moved to Kaua’i in 1978 and have always considered McBryde and Allerton Gardens as very special places. I fully support the mission of NTBG and love any excuse to spend time in the garden. Years ago I toured the BRC with a school group and told Tim Flynn that I would be back to help out in the herbarium after I retired. I retired from a 40 year career in education two years ago and now spend my Wednesday mornings mounting plant specimens.

Why is volunteering in this role important to you?

I think each of us has the responsibility to give back to our community. I’m happy I found a volunteer position that supports the mission of NTBG and brings me great pleasure and satisfaction as well.

Herbarium Digital Imaging

Herbarium Digital Imaging volunteers have the important task of digitally documenting thousands of specimens collected by NTBG scientists. Digitizing the collection allows this unique reference of natural history and a resource for researchers searchable online. Specimens can also be found through JSTOR Plants database.

Charlie Harrison, Volunteering Since 2020

What’s your favorite part about volunteering at the BRC?

My favorite part about volunteering is knowing that what I’m doing is useful and impactful to the community and NTBG. It’s also cool to meet (on occasion) some of the other people who work for NTBG and learn about how they are contributing.

Why is volunteering in this role important to you?

Through taking pictures for the cataloging of plant specimens, I’ve learned how far-reaching the work at NTBG really is. I’ve taken pictures of plants from Mexico to our very island and from as far back as the 1970s. It’s amazing to me that I may be volunteering on a small island in the Pacific, but the work truly is a global effort.

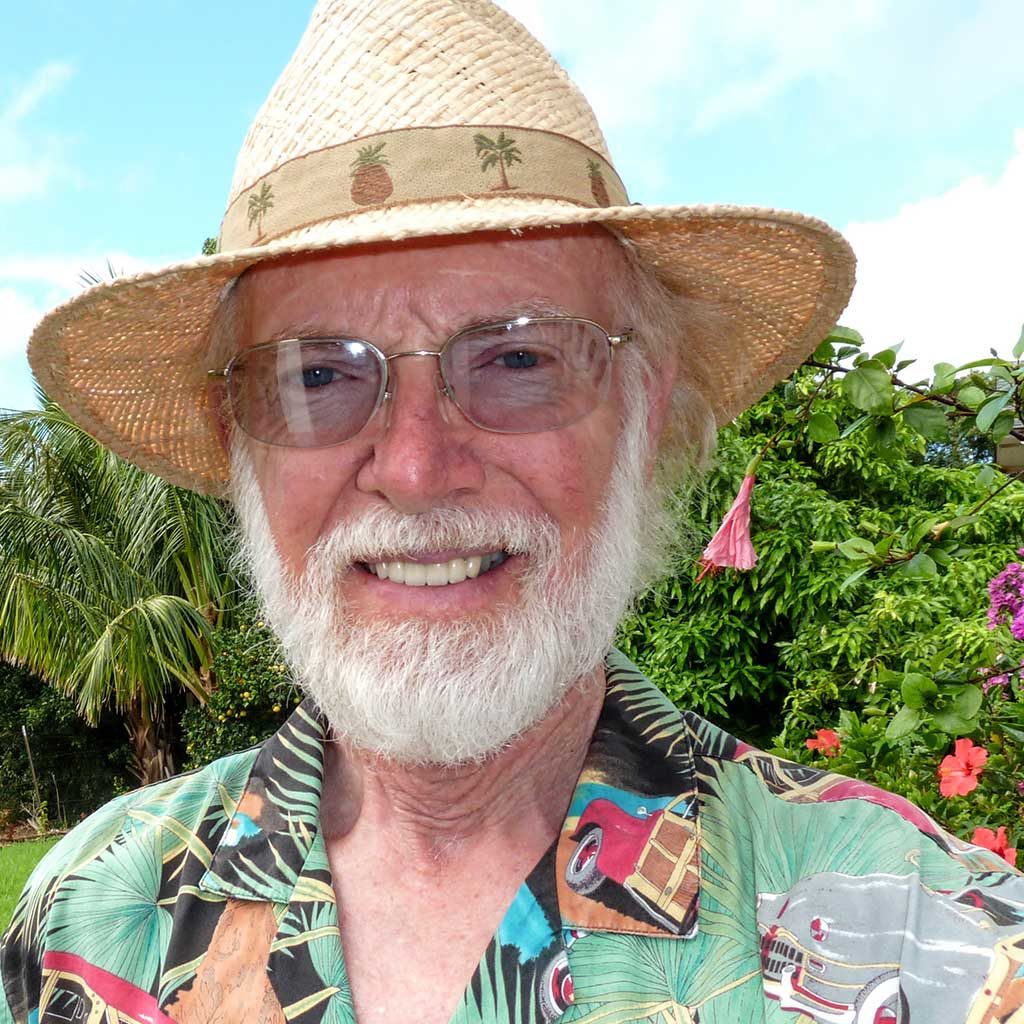

Neil Brosnahan, Volunteering Since 2008

What’s your favorite part about volunteering at the BRC?

Working with NTBG staff, I set up the photographic equipment and process technology that’s used to digitize and make available on the world wide web over sixty thousand herbarium specimens to date, allowing scientists and researchers around the world to view in great detail the specimen collection curated at the BRC. Formerly, physical specimens had to be shipped to the scientist or institution at significant expense. Today, only rarely, are physical specimens shipped, and many are small sample amounts for DNA identification and research.

Why is volunteering in this role important to you?

Making our herbarium resources at the BRC available around the world is immensely rewarding. Developing ways for other volunteers to join in makes it even more rewarding.

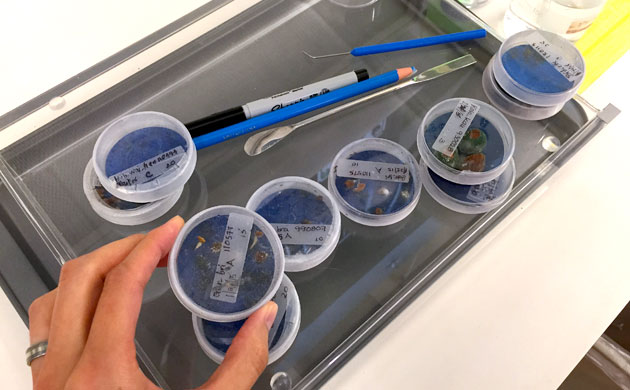

Seed Bank Assistant

Seed Bank Assistants help NTBG staff routinely check the viability of seeds stored in the bank. Seed banking is an important ex situ conservation means of rare and threatened flora and the NTBG Seed Bank and Laboratory currently includes over 15 million seeds representing 533 native Hawaiian taxa (892 total taxa, ecotypes and cultivars), which are routinely checked for viability.

John Steinhorst, Volunteering Since 2016

What brought you to the Botanical Research Center?

I believe conservation of Hawaii’s endemic plants is important, so I began volunteering with NTBG in 2016.

What is your favorite part about volunteering at the BRC?

My favorite part of volunteering at the BRC is learning about scientific techniques while studying Hawaii’s flora.

Why is volunteering important to you?

Volunteering is one way to benefit the island’s unique plants and be a contributing member of the community.

Leslie Ridpath, Volunteering Since 2019

What brought you to NTBG and the Botanical Research Center?

I am an avid gardener and volunteered with NTBG to learn more about tropical plants to help with my own garden.

What’s your favorite part about volunteering at the BRC?

I volunteer with the seed bank where I help test the viability of seeds in NTBG’s collection and with other scientific research projects. While science wasn’t my favorite subject in school, the team in the seed lab has made it easy and enjoyable to learn.

Why is volunteering in this role important to you?

It is very rewarding to know this work contributes to the preservation of rare and endangered Hawaiian plants.

Research Librarian

The library collection at NTBG houses more than 20,000 books, journals, botanical prints, and archival materials. With no librarian on staff, Lisa’s decades of experience in Library Science has been invaluable to maintaining this important collection.

Lisa Kostic, Volunteering Since 2020

What brought you to NTBG and the Botanical Research Center?

My husband Andy and I fell in love with Kaua’i on our first visit here in 2005. We spent the next decade and half waiting for our two kids to finish school and strike out on their own, all the while planning our retirement and a permanent move to the island.

NTBG was one place Andy and I always visited on our subsequent trips. Because we appreciate NTBG’s noble mission, we became members. Still, I felt I could offer not just financial support but also the benefit of my nearly 3 decades of experience as a library paraprofessional.

What’s your favorite part about volunteering at the BRC?

Currently, I volunteer in the Herbarium photographing preserved plant specimens for Dr. Tim Flynn, as well as in the BRC Library processing incoming books and periodicals for Dr. Lorence. I am also working on a project for Janet Mayfield to digitally image historic issues of The Bulletin going back 50 years. Lastly, when I have room in my schedule, I try to squeeze in a shift at the Nursery with Rhian Campbell.

Finding Climate Solutions with Ancient Knowledge and New Technology

On March 11, 2021, thick bands of heavy rain stretched across the Hawaiian Islands. While wet weather isn’t uncommon in the state this time of year, rainfall rates of more than 3 inches per hour certainly are. On the North Shore of Oahu, the storm caused catastrophic flooding and forced evacuations. On Maui, the intense rainfall washed out bridges, dams and damaged homes. On Kauai, landslides closed Kuhio highway in both directions at Hanalei; an area hit hard by the record-breaking rain bomb of 2018. All of the National Tropical Botanical Garden locations in Hawaii were closed, and some suffered damage to infrastructure and living collections.

Unfortunately, this kind of story isn’t unique to Hawaii. The climate is changing all around the world. Climate models project that tropical regions worldwide will experience more significant swings in temperature and rainfall, prolonged droughts, and a more substantial threat from tropical storms and cyclones.

How is Climate Change affecting the Hawaiian Islands, and What Can We Do?

“Climate change affects nearly every aspect of the human-natural ecosystems in the Hawaiian Islands,” says Dr. Uma Nagendra, Conservation Operations Manager and Ecologist at NTBG’s Limahuli Garden and Preserve. “Rising sea levels threaten roadways, houses, and coastal farmlands as well as endangered native lowland waterbirds. Increasing temperatures and droughts threaten local food security. On Kauai, we have seen firsthand how landslides, powerful storms, and wildfires can isolate and devastate entire communities and ecosystems,” she continued.

“Climate change affects nearly every aspect of the human-natural ecosystems in the Hawaiian Islands”

In April 2018, a massive storm dropped 50 inches of rain in 24-hours on Kauai’s North Shore, setting a new U.S. rainfall record. Streams overflowed, homes and highways washed away, and many large-scale landslides buried vast swaths of forest, destroying native plant habitat. Cliffsides were left barren, and exposed soil offered an open invitation to invasive weeds that don’t provide the same ecosystem services as native forests because many fast-growing invasive plants are shallow-rooted, which can leave the landscape vulnerable to further erosion.

After this record-breaking event, NTBG scientists and conservation professionals returned to the field and the lab to apply ancient knowledge, new science and technology to save plants and continue to bring local and global climate solutions into focus.

Learning from the Past

“The most important lessons we can learn from the past are how to adapt and be resilient as the world changes,” says Dr. Nagendra. “Part of that is taking care of the ecosystems that sustain us with fresh water, stable land, and food. During the 2018 flood, we saw thousand-year-old structures withstand heavy flooding that infrastructure from the 1970s couldn’t handle,” she remarked.

To build resiliency and protect ecosystems from the unpredictability of climate change, threatened and endangered native plants must survive in botanical gardens and their natural habitats. The Limahuli Valley is the second most biodiverse valley in Hawaii, making it the ideal location for NTBG’s watershed-based conservation program at Limahuli Garden and Preserve.

“The most important lessons we can learn from the past are how to adapt and be resilient as the world changes.”

The biocultural conservation program at NTBG’s Limahuli Garden collaborates with land stewards in the neighboring valleys to restore health and function to the social-ecological system that native Hawaiians have sustainably managed for more than 1,000 years. The ahupuaa system provides philosophies and practices for maintaining biodiversity, ensuring forest health, protecting stream integrity, creating fertile agricultural fields, promoting an abundant near-shore fishery from mauka to makai (mountain to ocean), and acknowledges that humans are part of the ecosystem.

New Solutions Take Flight

National Tropical Botanical Garden has a long history of plant exploration and discovery. Nearly 90% of Hawaiian plants don’t grow anywhere else on Earth and are particularly susceptible to competition from invasive species and climate change because they evolved in isolation. Since the mid-1970s, NTBG botanists have navigated, climbed, and rappelled challenging terrain to hand-pollinate and collect material, including seeds, from rare plants.

While NTBG botanists still work in the field, the addition of drone technology has allowed them to survey previously inaccessible areas and find new populations of rare plants – some thought to be already extinct in the wild. “In Hawaii, we are working as quickly as possible to collect, store and propagate rare plants in case suitable habitat disappears,” says Ben Nyberg, NTBG GIS specialist and drone pilot. “We are developing drone systems that can be applied by conservationists around the world to combat climate change in a number of ways, from survey to collection to reintroduction,” he continued.

Documenting and collecting plant material is one step in the conservation process. Once rare plant populations are discovered and seeds collected, NTBG and partners must work together to store and propagate the plants safely.

We are developing drone systems that can be applied by conservationists around the world to combat climate change in a number of ways, from survey to collection to reintroduction.”

Banking on Plants

Seed banking is a vital ex-situ or off-site conservation practice that helps protect plants from climate change, invasive species, and habitat loss. The NTBG Seed Bank and Laboratory currently store more than 15 million seeds from 533 native Hawaiian taxa. To store seeds wild-collected from native plants in the Limahuli preserve or remote cliffsides, seeds first must be meticulously cleaned to remove all fruit remnants. Once cleaned, information about when and where biologists collected the seed is recorded in NTBG databases, and research is conducted to determine if and how they can be stored long-term.

“Back in the early 1990s, we thought that because of our geographic location in the tropics, seeds of most species would not be able to be conserved using conventional storage methods,” says Dustin Wolkis, NTBG Seed Bank and Laboratory Manager. “Thanks to our collaboration with the Hawaii Seed Bank Partnership and other institutions, we have been able to conduct long-term monitoring and have found exactly the opposite,” he noted.

With more than 30 years of storage and viability data, NTBG and seed banking partner institutions can better understand trends and predict the storage behavior and viability of rare seeds giving new hope to many of Hawaii’s rare and endangered species.

“Back in the early 1990s, we thought that because of our geographic location in the tropics, seeds of most species would not be able to be conserved using conventional storage methods. We have been able to conduct long-term monitoring and have found exactly the opposite.”

Bringing It All Together

At the intersection of ancient knowledge, new technology, and seed science sits an exciting new research project that could be a game-changer for Hawaii’s endangered plants. NTBG conservation staff at Limahuli Garden are currently investigating the use of drone technology as a means of revegetating landslide areas on Kauai. “The extreme rain and numerous landslides we have already seen on Kauai are exactly what we expect to see from climate change,” said Dr. Nagendra. “Conservation staff at Limahuli are working with Ben and the drone program to develop ways of using drones to distribute seeds and revegetate exposed soil with native plants after landslide events. We’re currently using seed trays to test the idea and see if it’s viable,” she continued.

In addition to the possibility of revegetating with drones, ongoing research with DeLeaves and the University of Sherbrooke in Quebec is aimed at customizing drone sampling mechanisms to remotely collect plant material such as seeds or cuttings, and reach plant populations on steep or rocky cliffsides that have been largely unreachable. “Covid certainly delayed our field tests,” says Ben Nyberg, “but we have been able to collaborate and develop the robotics remotely. Field trials have been scheduled for later this summer and we are excited to get to work.”

Growing Green

Plants are one of our best defenses against our changing climate. They are the foundation of healthy ecosystems and can increase climate stability by offsetting temperature, moisture, and greenhouse gas fluctuations. From ancient knowledge to field surveys and seed storage, National Tropical Botanical Garden works at every level to discover solutions and save plants. You can help by. Visit our support page to see how you can get involved.

NTBG Completes IUCN Red Listing for all Kauai endemic plants

(March 25, 2021) Kauai, Hawaii — The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) updated the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species today. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is the world’s most comprehensive online source of information on the conservation status of the world’s plant, animal, and fungus species. Included in the updated list are 127 plant species unique to Kauai that were assessed in 2020. The effort was led by scientists at the National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG) and completes the assessment of all 255 Kauai single-island endemic vascular plants.

IUCN Red List assessments provide an essential tool for scientists and conservation managers around the world. By completing the Red List assessments for all of Kauai’s endemic plants, NTBG has verified that 5 percent are already extinct, another 5 percent are possibly extinct or extinct in the wild, with the remaining 90 percent classified as Threatened according to the internationally recognized IUCN Red List criteria. The majority of these were placed in the two highest categories: Critically Endangered (46 percent) or Endangered (41 percent), with only 3 percent assessed as Vulnerable.

At the same time, only 45 percent of these taxa are officially listed as Threatened or Endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, demonstrating the importance of bringing Hawaii’s conservation challenge to national and international attention through the Red List.

The Hawaiian Islands are known for having one of the world’s highest rates of endemism (species found only in one specific location). Over millennia, adaptive radiation has led to the evolution of a highly diverse flora of more than 1,360 native plant species. Among the eight main Hawaiian Islands, Kauai has the highest level of endemism and diversity, in part because it is the oldest island.

However, Hawaii’s flora is threatened by invasive species, changing land use, and more extreme weather. It is estimated that at least 134 of Hawaii’s native plant species have gone extinct since the 1840s. With all of Kauai’s known endemic vascular plant species assessed for the IUCN Red list, the goal of assessing the endemic species across the Hawaiian Islands will help better evaluate threat risks and aid in the formulation of conservation strategies.

Even as the assessment of Kauai’s endemic plants was underway, NTBG staff and its collaborators at the Department of Land and Natural Resources, Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the state of Hawaii’s Plant Extinction Prevention Program, made significant progress locating at least nine previously unknown populations of endangered native Hawaiian plants. Botanizing in rough terrain and remote locations, aided by helicopter transport and using drones and other new technology, NTBG discovered or re-discovered previously unknown plant populations in Kauai’s most challenging and inaccessible environments.

With today’s updated IUCN Red List, 134,425 species around the world have been assessed, 54,127 of them plants, each given a rank in one of nine categories from species of “least concern” to “extinct.” Twenty-eight (28%) percent of all now assessed species are recognized as Threatened.

The mission of the National Tropical Botanical Garden is to enrich life through discovery, scientific research, conservation, and education by perpetuating the survival of plants, ecosystems, and cultural knowledge of tropical regions.

Learn more about the work of the National Tropical Botanical Garden at ntbg.org.

For media inquiries, contact: media@ntbg.org

.svg)