By Dustin Wolkis, Seed Bank Curator and Laboratory Manager

The value of education and training in science and conservation has long been recognized by NTBG. This can take form in many ways but usually involves students at various levels. In the fall of 2021, what began as a high school science fair experiment testing the limits of storing or banking pollen, turned into an international collaboration that has added another tool to NTBG’s expanding plant conservation toolkit.

Plant pollen, which many people associate with hay fever, is much more than an allergen. Pollen grains house the “male” reproductive cells of flowering plants. Pollination is the transfer of pollen from a stamen (the pollen bearing part of a flower) to a stigma (the externally pollen receptive part). The ability to store or bank pollen creates the opportunity for conservation practitioners to make controlled crosses between individual plants.

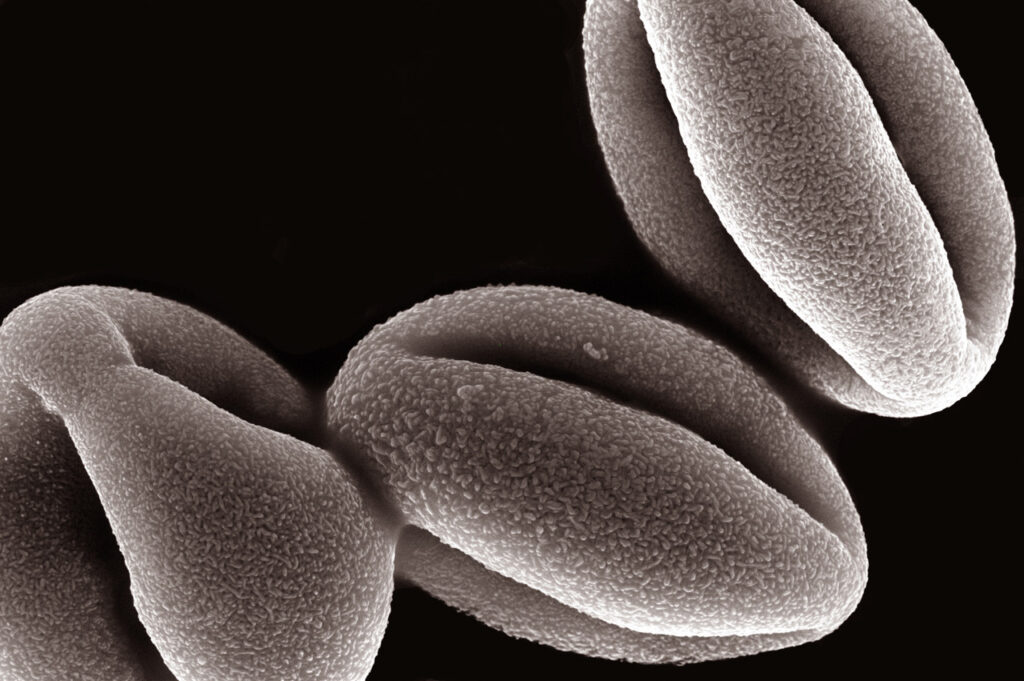

Dehydrated kanaloa kahoolawensis pollen grain image magnified 8,000 times. Photo by Radha Chaddah.

Pollen banking is a particularly useful conservation tool when plants are separated by distance which is common among rare species with fragmented populations or individuals. The same is true when plant reproduction cycles are separated by time which is increasing as climate change causes different flowering periods among individuals in the same species. Pollen banking can also aid botanists like NTBG conservation biologist Seana Walsh who is conducting research on how to minimize inbreeding among rare plant species such as the Kauaʻi endemic ʻālula (Brighamia insignis), found in collections at botanical institutions around the world.

Although NTBG has been banking pollen since at least 2016, until now there have been no studies on optimal pollen storage conditions. That is starting to change.

When trying to extend the longevity of pollen, as with seeds, desiccation (drying) pollen and airtight sealing in a low humidity environment is important. Moreover, if pollen can be dried, it can also likely be stored below freezing. If pollen is tolerant of both drying and freezing, its longevity can be extended many times over.

However, just as with seeds, pollen from different species behave in different ways when dried. Species-specific studies are needed to determine optimal storage conditions.

(L) Collecting pollen in McBryde Garden. Photo by Dustin Wolkis. (R) Pollen experimentation in NTBG’s seed lab. Photo by Katie Magoun.

In 2021, a team of three highly motivated students from Kauaʻi High School became interested in pollen banking after visiting NTBG’s Seed Lab. They chose to study one of Kauaʻi’s endemic palm loulu species (Pritchardia minor). These students harvested pollen from NTBG’s living collections as part of their project. Their study was simple: dry pollen to three different levels and compare viability with a freshly harvested control.

Creating the media necessary for pollen grains to germinate can be exceedingly difficult, so the team employed a stain commonly used to assess viability in seeds. The first task was to test the stain’s ability to detect pollen that was once viable but is no longer so. To do this the team placed pollen in an oven and compared viability as assessed with the stain against that of the freshly harvested control. The stain did indeed detect the newly dead pollen and so could be used for the desiccation tolerance experiment. The team found that Pritchardia minor pollen could be dried down to international standards, which is great news for the long-term pollen conservation of the species. The team also placed dried pollen at freezing temperatures before concluding their project.

Ultimately, the students’ project won several awards at the Kauaʻi Regional Science and Engineering Fair, including first place in the Biological Sciences category, leading them to advance to the state level competition where it won first place in Plant Sciences.

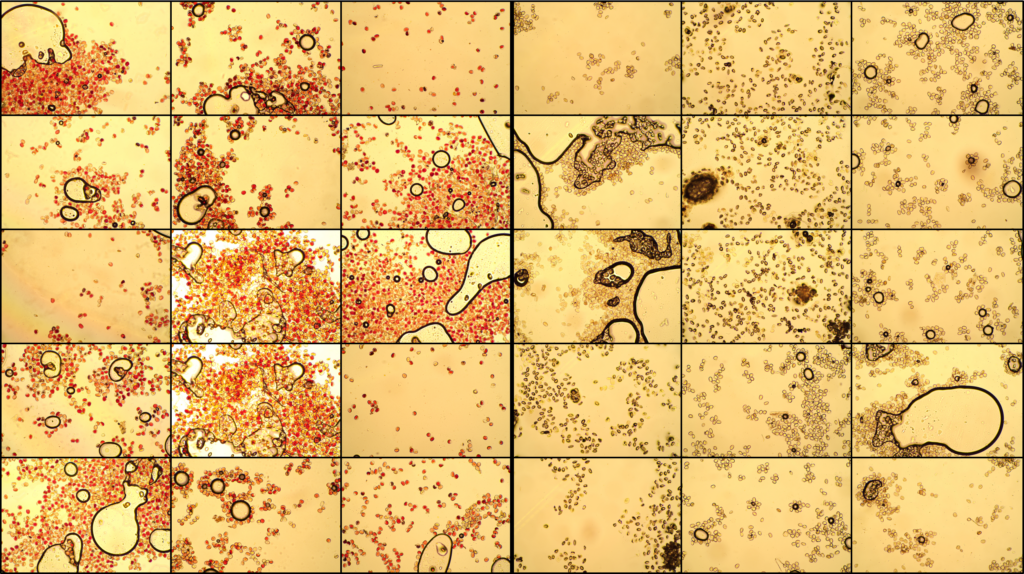

Panels representing single microscope views of pollen after oven treatment. Photo by NTBG staff/partners.

Several months later when Caroline Reize, a recent agro-ecology graduate from University of Cologne in Germany, contacted me about doing an internship in plant conservation at NTBG, I envision the dried and frozen pollen samples as the perfect project. Upon her arrival, Caroline focused on completing the high school pollen banking project as well as gaining firsthand propagation experience with conservation nursery manager Rhian Campbell.

Serendipitously, Caroline’s research stay at NTBG mirrored that of Danish Botany undergraduate student Clara Gråfelt Thomsen, allowing the two to room together. Clara had come to NTBG to observe pollination in two Hawaiʻi endemic species, ʻālula and maiapilo (Capparis sandwichiana) and so, with Caroline studying pollen conservation and Clara studying pollination, it was only natural that the two would help each other by “cross-pollinating” on their respective projects.

Clara and Caroline not only completed the high school freeze-tolerance portion of the project, but also started new pollen conservation projects using ʻālula and maiapilo. They had to figure out which stains to use for each species, and even attempted several recipes for germinating ʻālula pollen. The team also studied pollen longevity after drying to different levels. This research paired well with two master’s students conservation projects on the same species, respectively, that were already underway.

Although the results of this work are forthcoming, we have generated valuable data that will aid in the conservation of rare Hawaiian plant species. By working with students at three different levels (high school, undergraduate, and graduate) we have learned more than we could have on our own. Furthermore, this may have implications for global pollen conservation. NTBG will continue to increase our knowledge and experience in pollen banking, giving us another important tool to stem the tide of plant extinction.

Plants nourish our ecosystems and communities in countless ways. When we care for plants, they continue caring for us. Help us grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants.