The Generations-long Effort to Save Hawai‘i’s Favorite Cliff Dweller

By Jon Letman, Editor

Writing in A Monographic Study of the Hawaiian Species of the Tribe Lobelioideae Family Campanulaceae in 1919, botanist Joseph Rock described the genus Brighamia as “one of the most curious Hawaiian Lobelioideae, though not one of the handsome ones.” Rock noted that renowned American botanist Asa Gray named the succulent genus for Dr. William T. Brigham, the first director of Honolulu’s Bishop Museum.

Cabbage on a Fence Post

Describing the species that would later bear his name — Brighamia rockii — the Vienna-born botanist wrote unflatteringly: “It certainly is a most grotesque plant.” German botanist William Hillebrand, who preceded Rock in Hawaii by half a century, compared Brighamia to a “cabbage put on a fence post.”

Lobeliads, to which Brighamia belongs, found their way to the Hawaiian Islands some 13 million years ago in a single migration, evolving into 159 endemic taxa of Campanulaceae (bellflower family).

Rock was certain that Brighamia migrated from Australia, perhaps as one of the last of the Lobeliads to arrive in Hawaii and, as a result, lacked sufficient time to speciate before animals and humans began to present a threat.

Brighamia insignis and Brighamia rockii

In the early 1900s Brighamia was classified as a monotypic[1] genus although botanist Charles Forbes differentiated between the Brighamia on the cliffs of Kauai with their yellow flowers which inspired the species name citrina, and the Molokai form which bears white flowers. Today they are recognized as two species, B. insignis and B. rockii respectively. In Hawaiian they’re best known as alula or puaala.

Viewed side by side, they differ only slightly in appearance except for the color of the flowers. Other differences — calyx lobe size, leaf shape, seed surface — are very subtle.

Rock documented Brighamia’s habitat in the early 20th century — the steep, windward cliffs of Niihau, Kauai, Molokai, and Lanai. He reported seeing Brighamia on the cliffs of the Kalaupapa peninsula of Molokai and “on almost bare rockwalls between Kalawao and Waikolu, within the spray of the sea, only a few feet above the mighty breakers of the Pacific.”

He also reported Brighamia growing in the dry, rocky gorges at the entrance to Molokai’s Halawa Valley. French botanist Jules Remy collected a single specimen in the early 1850s and the last Brighamia seen on Niihau was in 1947.

Searching the Known Habitat

It was another botanist, Harold St. John, serving as a scientific advisor for NTBG in the mid-1970s, that first suggested to a young nurseryman and field botanist named Steve Perlman to search for, collect, and grow Brighamia. Perlman was unfamiliar with the genus but began searching the known habitat.

Over the next three decades, Perlman, along with fellow NTBG botanist Ken Wood, climbed, rappelled, hand pollinated flowers, and later collected the tiny seeds as they defied gravity, roping along the vertigo-inducing cliffs of Kauai and Molokai.

Among their findings, they located several plants along the upper cliffs of Molokai’s Wailau Valley, but those plants are now gone. They spent years searching for B. rockii in the Halawa Valley, but found none. Perlman and Wood also collected seeds on Huelo Rock off Molokai but those plants are now gone. Perlman spotted B. rockii on Molokai’s Kaaloa cliffs and a few plants may remain.

Wild Brighamia Populations

The largest remaining wild population of B. rockii is on the cliffs of Waiehu, east of Wailele falls, but a series of landslides has rendered the area too hazardous to work and NTBG botanists haven’t been back since they last roped down to the site in 2011. The last known seed collection of B. rockii was by staff of the Plant Extinction Prevention program in December 2014. Today there are an estimated 30 plants remaining on Molokaii’s seacliffs.

On Kauai, B. insignis populations crashed after Hurricane Iniki devastated the island in 1992, with the last plant dying on Mt. Haupu in 2002 and the last one seen on the Na Pali Coast around 2015.

With the threat of landslides, hurricanes, feral goats, rats, and the loss of the suspected pollinator, a giant sphinx moth, wild Brighamia spp. hover just above extinction.

Between Kauai and Molokai, on the island of O‘ahu, there have never been credible claims documenting Brighamia. If it ever did exist there (nothing suggests that is so), one could posit that with limited field collectors and the difficulty of accessing steep cliff terrain, any plants might have vanished before they were discovered.

Working to Save Species

Spanning more than 30 years, NTBG botanists have collected seed from all Brighamia spp. colonies, making repeat visits to conduct pollen exchanges by hand, and returning to collect seed for deposit at NTBG’s Conservation and Horticulture Center. Garden staff determine if seeds are put into storage or propagated for outplanting. NTBG usually has anywhere from 50 – 250 B. insignis and less than a dozen B. rockii in the greenhouse for planting in the gardens.

Multiple attempts at outplanting B. insignis have been made with some of the most successful results in the relatively protected Limahuli Valley which is near their native habitat.

Perlman says, “We would like to have some protected areas to do outplanting of species…the best way to keep that species the same and alive is to put it back where it evolved, where you have the same rainfall and same kind of soil.”

Pollination and Seed Banking

Having hand-pollinated and collected tens of thousands of seeds, NTBG staff have partnered with Kalaupapa National Historic Park on Molokai whose natural resource managers have planted B. rockii on the cliffs as part of restoration efforts.

On Kauai, NTBG’s Seed Bank and Laboratory currently houses over 15,000 seeds from 52 accessions representing B. insignis and more than 11,000 B. rockii seeds from 23 accessions.

Seed Bank and Laboratory Manager Dustin Wolkis notes that Brighamia spp. represent some of the NTBG’s earliest seed collections, going back 24 years. Part of storing seeds at NTBG is conducting germination trials to better understand how long seeds can be stored and how to increase longevity. The seeds are desiccation tolerant but decline more rapidly at -18°C (conventional storage temperature) compared with cool +5°C.

Genetic material is also stored by the University of Hawaii’s Lyon Arboretum Hawaiian Rare Plant Program which has over 100 in vitro Brighamia spp. seedlings, as well as some 20,000 seeds (6,000 B. insignis and 14,000 B. rockii) banked. Additional seed collections are held by the National Laboratory for Genetic Resource Preservation in Colorado, and elsewhere.

For over a century, Brighamia has captured the imagination of botanists and fueled their passion for rare plant conservation. This includes Seana Walsh who, prior to accepting a position as a conservation biologist at NTBG, completed her Master’s thesis on the floral biology, pollination ecology, and ex situ genetic diversity of B. insignis.

Walsh has gone on to help establish collaborations between NTBG, Chicago Botanic Garden (CBG), and others who are conducting ongoing studies of genetic diversity of Brighamia. Based on these results, researchers at CBG are developing and implementing an ex situ conservation management plan for the species that considers lessons learned by zoologists with similar genetic management goals.

Cultivation

Besides outplanting live plants and storing living genetic material, growing B. insignis in cultivation and sharing widely among botanic gardens and the horticulture industry has increased plant numbers to the tens of thousands. These efforts stem from Perlman, who began sending Brighamia seeds to other botanical gardens, first across the U.S. and then in Europe where they caught the attention of commercial nurseries in the Netherlands and elsewhere. According to the sourcing guide PlantSearch, B. insignis is cultivated ex situ in at least 55 botanical collections.

In recent years, B. insignis has taken off as a wildly popular house plant sold in Europe as the “Vulcan palm” or “Hawaii palm.” And while there may be only one B. insignis and just a few dozen B. rockii left in the wild, today there are thousands of B. insignis growing in cultivation, all but ensuring they won’t fade away any time soon.

From a conservation standpoint, commercially grown cultivated plants may not be the ideal end goal, and yet the botanists who have spent decades literally risking their own lives to find, collect, and save these gems of plant evolution say it’s better than the alternative: an endemic plant genus abandoned on remote cliffs, left on its own to slip quietly and unnoticed into the permanence of extinction.

[1] A genus with only one species

Eye on Plants: Hibiscus kokio subsp. saintjohnianus

In 1955, a 37 family-strong community alliance called Hui Kuai Aina o Haena that had owned the ahupuaa (watershed and coastal lands) of Haena on Kauai’s north shore for nearly 100 years, began partitioning the region. By 1967, a third-generation member of the group, Juliet Rice Wichman, had negotiated ownership Haena’s Limahuli Valley.

A Love of Hibiscus and Hawaiian Plants

Juliet, a lover of Hawaiian plants, with a passion for collecting and growing hibiscus, had a vision to protect Limahuli which she recognized as culturally important and ecologically fragile. In 1967, she began removing cattle from the valley so the plants could start to recover. She also launched the restoration of centuries-old dry-wall style kalo loi (taro terraces).

By 1976 Limahuli was home to a small but growing botanical garden where 3,300-feet high valley walls had sheltered undiscovered rare plants for centuries.

Seeking to ensure her vision of restoration would continue in perpetuity, Juliet and her son Charles gifted the 13-acre Limahuli Garden to the PTBG — Pacific Tropical Botanical Garden. In 1994, the property grew to over 1,000 acres when Juliet’s grandson Chipper and his wife Hauoli gifted the entire valley to the Garden.

That Garden (now called NTBG) accepted the kuleana (responsibility) to malama (care for) the land as Juliet and others had done before. PTBG Director Dr. William Theobold recognized that because Limahuli had never been cultivated for large-scale agriculture, it held great promise for undiscovered native plant varieties, forms, and possibly even endemic species.

In 1977 Theobold called for the first-ever botanical survey of the valley, assigning the task to staff including Chipper who, at the encouragement of his grandmother, had completed the Garden’s internship in 1977 and was working as a head groundsman.

Hidden in the Valley

That summer Chipper, along with other staff, explored Limahuli’s deepest recesses, gullies, ridges and streamside. Among their findings: at least 88 Polynesian introduced and rare, endemic species including Lobeliods, Cyanea, Psychotria, native sandalwood (iliahi), ebony (lama), and many others.

Chipper reported finding two new color variations of Hibiscus saintjohnianus which had been previously identified as endemic to Kauai’s Na Pali Coast. The newly discovered forms (later classified as Hibiscus kokio subsp. saintjohnianus) extended the species’ known range and diversity.

In the PTBG Bulletin of January 1978, Chipper wrote: “One of the forms we found has bright orange petals with a creamy yellow, almost ivory colored staminal column, while another form has petals which are red with just a tinge of orange.”

In the late 1990s, noted wildlife photographers Susan Middleton and David Liittschwager spent months documenting life in the Hawaiian Islands for what would become their landmark book Remains of a Rainbow: Rare Plants and Animals of Hawaii. When they came to shoot in Limahuli Valley, they worked closely with Chipper.

Years later, Middleton recalled her introduction to kokio ulaula. “Chipper enthusiastically showed me what was clearly one of his favorites — a shrub with deep green leaves and striking orange flowers.”

Bold And Bright

Unlike other Hawaiian flora which she found to be subtle, even shy, kokio ulaula was bold and bright. Middleton remembers thinking, “stunning — a world class plant!”

“They must have taken 500 photographs…” Chipper said of the encounter. The shoot resulted in Limahuli’s brilliant orange hibiscus being featured prominently on the title page of the iconic book.

Decades later Middleton still associates the striking orange hibiscus with Chipper and the Limahuli Valley. Kokio ulaula, she says, represents “the exquisite beauty, elegance, and value of Hawai‘i’s rare native plants.”

NTBG’s Seed Bank: An Investment Pays Off

From humble beginnings, NTBG’s Seed Bank and Laboratory has grown into a valuable repository for Hawaii’s irreplaceable genetic botanical wealth

By Jon Letman, Editor

Although its name often goes unmentioned, the island of Kahoolawe sits at the heart of Hawaii, both physically and spiritually. Part of the ancient geologic formation Maui Nui (Greater Maui), the 45-square-mile island with the jagged coastline is roughly triangular in form with deeply indented coves and a club-shaped peninsula on its southern coast.

The island, revered as a physical manifestation of the ocean deity Kanaloa, is sacred to Native Hawaiians who see it as a place of recovery and restoration. Kahoolawe is the piko (navel or center) of Kanaloa and has been called the crossroads of past and future generations of Hawaiians.

Perched in the lee of Maui’s towering volcano, Haleakala, Kahoolawe is one of the driest of the main Hawaiian Islands, receiving less than 25 inches of rain a year. Just 11 miles long and seven miles wide, the island has suffered the ravages of wild goats (introduced as a gift by Captain George Vancouver in 1793), cattle and sheep ranching, and more than half a century of bombing and military testing by the U.S. Navy (1941-93).

By 2004, unexploded ordnance (UXO) had been cleared from about 75 percent of Kahoolawe’s surface, but today only about 10 percent of the island is considered safe to dig to the depth of four feet — no deeper. Additionally, 25 percent of the island remains uncleared of UXO with access restricted and restoration work strictly controlled.

Rugged but Fragile Environment

Administrating the island’s rugged but fragile environment is the Kahoolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC), whose mission includes the restoration of the island’s dryland forests, shrublands, and the surrounding reef ecosystems. KIRC operates with funding from individuals, grants, and state funding.

Under KIRC’s management, the island is gradually recovering, but outplanted seeds and seedlings still face multiple threats. Drought, flash floods, erosion, seed predation from rodents, invasive plants, and insects such as the Erythrina gall wasp and bruchid beetle all pose formidable threats.

Since the 1990s, NTBG Research Biologist Ken Wood, occasionally in collaboration with fellow botanists, has been collecting seeds from the gulches, cliffs, and coastlines of Kahoolawe and its steep offshore islet Puu Koae, and seastack Aleale. Collections have focused on a dozen Hawaiian species that include ihi (Portulaca molokiniensis), native caper maiapilo (Capparis sandwichiana), and other shrubs, trees, and vines that can survive the island’s inhospitable conditions.

Between 1995 and 2001, 194 collections (accessions) were made and deposited in NTBG’s then-nascent seed bank on Kaua‘i. In 2008, all of those seeds were transferred to frozen (-18°C) or refrigerated (+5C°) storage.

Until 2017, KIRC had withdrawn only a very limited number of seeds from NTBG for reintroduction to Kahoolawe, but grant funding from the Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources Commission on Water Resource Manager-Water Security Advisory Group in 2017 allowed KIRC to request nearly half of the seeds[1] of target species including two members of the legume family — Erythrina sandwicensis or wiliwili tree, and Sesbania tomentosa or ohai, which grows as a coastal shrub. Three-thousand seeds from the native Hawaiian cotton (Gossypium tomentosum) or mao, were also sent to KIRC.

The Journey Home

Last November, as she prepared the seeds for their journey home, NTBG Science and Conservation Specialist Margaret Clark explained, “I’m sending samples of each of these parent plants so that they have the widest possible genetic representation, because the more genes that are in the pool that they plant, the more diversity there will be in succeeding generations, and the more long-term survivorship there’ll be.”

Opening a foil packet, Margaret gingerly removed a handful of fluffy brown mao seeds, holding them like tiny cotton balls. “They’re real soft, but they’re not as long-lived, we think, as the Erythrina and the Sesbania. We’ll see.”

With uncertain survival rates, KIRC has requested twice the number of seeds it expects to plant out to allow for seeds that might not germinate.

Once KIRC receives the seeds from NTBG, they will be grown out at a nursery on Maui. Plants will then be hand-carried back to Kahoolawe for outplanting during the wetter winter months.

James Bruch, a KIRC Natural Resources Specialist, says the reintroduction of plants, and the native insects that will follow, is a first step in restoring the habitat. Because much of Kahoolawe’s land is still not safe for digging, KIRC has developed a technique to revegetate on the surface in soil planter beds built on top of hardpan.

“We really appreciate the service that NTBG is doing because without it, we wouldn’t be able to do projects like this,” says James.

KIRC’s planting, which began in March, is expected to continue through June. As the partnership between KIRC and NTBG shows, seed banking is one sound investment that offers a payback with real growth potential.

[1] KIRC has requested 600 Erthrina, 1,000 Sesbania, and 3,000 Gossypium seeds.

Exploring Hawaiian Life Through Canoe Plants

A New Place to Experience the Ancient Story of Canoe Plants in McBryde Garden

By Jon Letman, Editor

NTBG’s flagship McBryde Garden contains an interpretive collection that allows visitors to experience the plants of Hawaii in a new way. The Hawaiian Life Canoe Garden was designed as a showcase for plants the first Hawaiians introduced to the islands, Hawaiian Life creates a sense of place, helping visitors better understand the central role plants play in Hawaiian culture, while serving as a living classroom.

At the heart of the collection are more than two dozen species known as “canoe plants.” Staple crops such as kalo (taro), ulu (breadfruit), and uala (sweet potato) were introduced to Hawaii by the first voyagers to reach the islands.

Braving the open ocean in waa kaulua (double-hulled voyaging canoes), the first humans migrated in waves from the Marquesas Islands, Tahiti, and other island groups over centuries, carrying plants essential to their survival and the perpetuation of their culture.

Navigating to Hawaii

Armed with extraordinary navigational skills, and carrying only the most important plants, animals (pigs, dogs, chickens), food, and water, those first wayfinders overcame extraordinary odds, crossing an ocean that was anything but pacific, to reach the world’s most isolated archipelago — a string of high volcanic islands where plants and animals found nowhere else had evolved in quiet isolation.

The roughly two dozen new plants those first navigators introduced to Hawaii are at the core of the story of NTBG’s Hawaiian Life. This redesigned space features new exhibits that are more interactive, trails that are more accessible, and plant collections presented in a more cohesive, narrative manner with specially designed signs, story panels, and breakout spaces along the trail to gather and share stories. From these overlooks, visitors can better observe their surroundings or watch demonstrations, when offered, on the hula mound, at the planting beds, or inside the hale (traditional thatched house).

Culture Cannot Survive Without Plants

Sabra Kauka, a respected kumu (teacher) and cultural practitioner, has taught students in McBryde Garden for many years. As an educator and advisor for the Canoe Garden, Sabra knows the important role the plants play in perpetuating cultural knowledge. “The culture cannot survive without the plants,” she says. “Each plant has a story to tell. Each was carefully chosen by my ancestors.”

Walking the new trail is like embarking on a journey that begins at an interpretive station where a wooden paddle sign and a canvas “sail” pulled taut between mast-like posts evoke the image of a voyaging canoe. The trail winds beneath a stand of hala (pandanus), passing overlooks of the Lawa‘i stream, leading to Hale Ho‘ona‘auao (literally: House of teaching). Surrounding planting beds are filled with awa (Piper methysticum), ape (Alocasia macrorrhiza), and the rarely seen auhuhu (Tephrosia purpurea), a plant used to temporarily stun and catch fish.

The construction of Hawaiian Life provided an opportunity to perpetuate the practice of building kalo loi (taro terraces) using lava rocks from the garden. The new loi function much as they did centuries ago, routing water to the taro in the terraces before flowing into the stream.

Star Compass

A central feature of the Hawaiian Life Canoe Garden is a sidereal star compass based on a design used by navigators, recreated with permission from renowned Polynesian navigator Nainoa Thompson. Measuring eight feet in diameter, the tile compass lies flat at ground level and displays the four cardinal directions: akau (north), hema (south), hikina (east), and komohana (west), and four quadrants named for the prevailing winds (Koolau, Malanai, Kona, and Hoolua).

The compass is further divided into 32 houses representing celestial spheres. Each house bears one of seven names: Haka, Na leo, Nalani, Nanu, Noio, Aina, and La, each separated by 11.25 ° for a total of 360°. At the center of the compass is the image of a soaring iwa — the pelagic frigate bird often seen soaring effortlessly above the seas.

While Nainoa’s star compass is a “mental construct for navigation” based on Micronesian traditional wisdom perpetuated by wayfinders, NTBG’s rendering, built with tiles encircled by concrete pavers, is a distinctive feature and an educational tool that conveys the importance of navigation in Hawaiian and other Pacific Island cultures.

Brian Yamamoto, Kaua‘i Community College professor of natural sciences and longtime NTBG partner, says Hawaiian Life is important because it’s one of the few places he can take his students to examine the full range of canoe plants in a single location. NTBG’s outdoor classroom, Yamamoto explains, allows students to have a more impactful and enjoyable experience by working directly with the plants.

As the Hawaiian Life Canoe Garden grows and matures, it will serve students, cultural practitioners, the broader community, and island visitors as a botanical sanctuary filled with tropical beauty, traditional wisdom, and inspiration, where one can come to better understand and appreciate Hawaiian culture and plants, feed the imagination, and nourish the soul.

The Hawaiian Life Canoe Garden was made possible with support from NTBG’s McBryde Garden Planning Committee, the Hawaii Tourism Authority, Emerson and Peggy Knowles, and other generous donors.

An Island Apart: Notes on Kahoolawe Seed Collections

By Kenneth R. Wood, Research Biologist

Isolated and with no permanent residents, the island of Kahoolawe is veiled in a deep, penetrating stillness that floats out toward the vast blue horizons of day and star-spinning heavens of night.

The waters surrounding Kahoolawe are clear, sparkling, and rich with sea life, while its landscape holds many mysteries hidden in thousands of archeological sites and features. Early Hawaiians dedicated Kahoolawe to Kanaloa, Hawaiian deity of the ocean, and used the island as a place to study celestial navigation. Although Kahoolawe is the smallest and one of the driest of the major Hawaiian Islands, it continues to have great significance to Hawaiians.

Studying the Flora of Kahoolawe

Since I began my studies of the flora of Kahoolawe, I have made over 50 visits, exploring a majority of its arid gulches and coastal sites. My research was focused around the Kamohio Bay region which harbors the inspiring Aleale seastack and the nearshore islet of Puu Koae.

One of my earliest visits to Kahoolawe was around the vernal equinox of 1992 when I found myself in a magical realm. A mother and baby whale were splash-dancing in Kamohio Bay, brown boobies and other seabirds were calling along the seacliffs, and spring echoed in the earth, sea, and air. I explored and rappelled Kahoolawe’s dangerous southern seacliffs down to their crumbling base, and pushed myself further to ultimately climb the adjacent Aleale.

In those forthcoming moments a new endemic Hawaiian genus of plant was found, and was given the most appropriate name, Kanaloa kahoolawensis, by NTBG’s Director of Science and Conservation Dr. David Lorence.

Subsequently over the next few decades, NTBG continued to support our Kahoolawe research, allowing me to partner with staff from the Kahoolawe Island Reserve Commission (KIRC) and others, and we were able to collect seed of Kanaloa and cultivate several individuals. Although this genus has since gone extinct in the wild, several Kanaloa plants still survive on Maui from seed collected during these visits. Today those young — yet evolutionarily ancient — trees give hope to the future of Kanaloa and to those who wish to perpetuate the Hawaiian flora.

Seed Collections

From 1992 to the present, NTBG and the KIRC have collected seed from almost all the wild native plant species we encountered on Kahoolawe. One especially rewarding seed conservation effort took place during the turn of the century when I teamed-up with Maya LeGrande, a Master’s student at the University of Hawaii, Manoa. Her research focused on the charismatic dry forest tree, wiliwili (Erythrina sandwicensis [Fabaceae]) which occurs throughout the main Hawaiian Islands.

As dry forests are the most drastically altered and endangered ecosystems in Hawaii, I keenly supported her research. On Kahoolawe we tagged, mapped, and collected seed and DNA from as many naturally occurring wiliwili as we could find. Maya’s thesis work centered on the supposition that the preservation and conservation of wiliwili populations may be critical for the success of other native dryland forest species.

In the end, we mapped 75 mature wild wiliwili individuals along with 34 juveniles, all mostly around the upper Kaukamoku and Puu Moaulanui region of Kahoolawe and we achieved our goal of preserving a significant percentage of their genetic variability. Sadly, following this research several groupings of those wiliwili trees burned-up in a wild fire, while others were negatively impacted by infestations of Erythrina gall wasps and bruchid beetles. It felt timely and fortunate that we facilitated our conservation collections prior to those events.

Conservation, Restoration and Outplanting

In 2002 I worked closely with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Dr. Michael Maunder, then NTBG Chair of Conservation, to create the Offshore Islet Restoration Committee (OIRC) whose goal was to inventory, protect, and make conservation collections from all of Hawaii’s offshore islets and I spent many years as the principal islet biologist.

One important focus of the OIRC was Kahoolawe’s islet, Puu Koae, where there is a very rich population of endemic ohai (Sesbania tomentosa [Fabaceae]). I loved this colony of ohai which grew alongside the endangered ihi (Portulaca molokiniensis [Portulacaceae]) and I considered the Puu Koae ohai to be the most attractive ecotype of the species. With around 300± shrubs, depending on seasonal rainfall, we collected and stored seed of this beautiful and rare dryland shrub for many years.

In my most recent attempts to collect ohai seed on Puu Koae, I’ve been finding undeveloped seed which may be the result of flower predation by larval insects, lack of pollinators, or perhaps some fungal pathogens. This recent absence of seed production once again demonstrates the importance of timely collections and the need for life-cycle studies of our endangered flora.

During my overnight stays on Kahoolawe, I would reside along the southwestern shore where there is an old navy base in Hanakanaea. At the end of our long work days, and if there was still some daylight left, I would hike to the adjacent coastal shrublands near Honukanaenae, Lea o Kealaikahiki, and Kaukaukapapa to make seed collections from Hawaii’s native cotton, mao (Gossypium tomentosum [Malvaceae]). This species has my great admiration with its silvery-green leaves, translucent multi-colored bracts, and yellow hibiscus-like flowers.

For me it is a certainty, that the mao, and all of Kahoolawe’s wild native plant populations, great or small, are evolutionarily significant and invaluable for restoration and out-planting efforts. I feel grateful to all who have supported these collections; most notably KIRC who are on the front line of dry shrubland and forest restoration and NTBG whose mission statement prescribes collecting and cultivating tropical floras’, especially those that are threatened with extinction.

The Life & Legacy of Catherine “Kay” Hauberg Sweeney

Savior of The Kampong

By Jon Letman, Editor

Half a planet away from the frozen Antarctic peaks that would one day bear her family name, Catherine Denkmann Hauberg was born in 1915 along the banks of the Mississippi River in Rock Island, Illinois.

“Kay” (as her younger brother called her), was the granddaughter of German-born Frederick Denkmann who, with his brother-in-law, Frederick Weyerhaeuser, launched what would become a lumber empire that later enabled her to be a patron of education, exploration, music, art, and plant conservation, ultimately becoming the “savior of The Kampong,” NTBG’s garden in Coconut Grove, Florida.

Kay was a quiet, but ambitious girl. Inheriting her father’s sense of curiosity, she memorized the names of the trees, birds, and wildflowers that lived in the woods surrounding her home. Her fascination with nature grew when, at the age of 19, Kay’s cousin, a botanist at Chicago’s Field Museum, took her to Guatemala on an orchid collecting trip.

After graduating from boarding school in Massachusetts in the early 1930s, Kay earned a degree from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign before studying zoology at the University of Arizona.

In 1938 Kay became Mrs. Sweeney when she married Edward C. Sweeney, a professor of aviation law and one-time president of the Explorer’s Club. The newlyweds moved to Washington D.C. and before long she was busy raising two daughters and three sons.

The modest Mrs. Sweeney, who also enjoyed caring for flower beds and pottering about the garden, once referred to herself as “just a lady gardener,” but she possessed a strong will, independence, and endless curiosity. She wasn’t an extrovert, but always made time for anyone seeking her acquaintance.

A Passion for Plants

Mrs. Sweeney’s passion for tropical plants was fueled by travels in Mexico, East Africa, and South Asia. As a board member of the U.S. National Arboretum in the 1950s and 60s, Mrs. Sweeney enjoyed traveling with her friend Edith “Jackie” Ronne whose 1947-48 Antarctic expedition she helped fund and was recognized with the naming of the Sweeney Mountains.

It was during a trip to Miami that she and Jackie visited the Fairchild Tropical Botanical Garden where Mrs. Sweeney posed a plant question. After it was suggested that she pay a visit to the garden’s namesake, renowned plant explorer Dr. David Fairchild, who lived just up the road in a compound he called The Kampong, Mrs. Sweeney found the botanist was not only home, but all too happy to help.

“What may I do for you ladies?” the mustachioed Fairchild asked.

A Chance Encounter

What might have otherwise been just a chance encounter between Fairchild and Mrs. Sweeney, laid the groundwork for what would decades later form the union of the Fairchild’s private estate and the Pacific Tropical Botanical Garden (PTBG) in Hawaiʻi.

David Fairchild died in 1954 (nearly ten years to the day before PTBG was established) and after his wife passed away in 1962, Mrs. Sweeney was contacted by a relative of Fairchild’s who she had known from Washington. When asked if she was interested in buying The Kampong, Mrs. Sweeney leapt at the chance.

Initially, her husband was taken aback, but the idea of retiring in south Florida did have its appeal and so, in 1963, the Sweeneys purchased The Kampong, a move that protected the property from what almost certainly would have been a future of subdivision and development.

Mrs. and Mr. Sweeney traveled between Washington and The Kampong for several years, staying in the property’s Barbour Cottage until garden renovations were complete. After Mr. Sweeney passed away in 1967, Mrs. Sweeney permanently moved down to Florida.

As the new owner of The Kampong, Mrs. Sweeney continued to travel in the tropics. It was during a trip to Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon) in February 1966, that Mrs. Sweeney was introduced to a young tea plantation manager named Larry Schokman. The two became fast friends with Larry serving as driver and guide, leading Mrs. Sweeney as they explored the flora and fauna of the central highlands on the first of her three visits to the island.

In the Company of an Adventurer

In a 2014 interview, Larry described how while winding along mountain roads Mrs. Sweeney would direct him to pull off to the side so she could examine, photograph, and collect whatever plant happened to catch her eye. He later realized he was in the company of his first botanical adventurer. “Whether one collects 20,000 plants or 20 plants,” he said, “a plant explorer is a plant explorer.”

Recounting how she thrust her hands beneath rocks to collect plants, Larry called out to his fearless companion, “Kay, don’t do this — there are cobras and vipers. This is the bloody heart of the tropics for godsakes!”

Larry’s wife Colleen also recalled traversing Sri Lanka with her husband and Mrs. Sweeney, watching in amazement as the robust 50-some-year-old woman scampered up steep slopes at 5,000 feet, pulling plants from underneath rocks to take home and painstakingly press each night.

After the Schokmans relocated from Sri Lanka to the U.S., Mrs. Sweeney invited Larry to work for her at The Kampong as superintendent in the spring of 1974. On Larry’s first day in Miami she presented him with a copy of David Fairchild’s book The World Was My Garden: Travels of a Plant Explorer, saying, “I would like you to read it and we can discuss it sooner rather than later.”

His long association with Mrs. Sweeney, Larry said, opened his mind in more ways than he could describe, and led him to eventually serve as Director of The Kampong where he lived and worked alongside Mrs. Sweeney for more than two decades.

Larry recalled fondly how Mrs. Sweeney hosted extraordinary visitors who engaged in lively discussions of art and architecture, politics, plants, and world travels with their unassuming hostess. Mrs. Sweeney was, in Larry’s words, “remarkably intelligent and strong” with “no false airs and graces.” Colleen called her “just a lovely person.”

A Lasting Legacy

A dozen years after Mrs. Sweeney had become a member of the PTBG Board of Trustees, she made the decision to gift her home to the Hawaii-based organization in 1984, the same year The Kampong was added to the National Register of Historic Places. The addition of a garden in Florida gave PTBG the opportunity to petition Congress to change its name to National Tropical Botanical Garden[1], reflecting the fact that it now had a property in the other tropical part of the country.

Mrs. Sweeney continued to live at The Kampong until her death in January 1995, leaving behind a rich legacy of helping people and saving places. Throughout her life, Mrs. Sweeney was a “patron of arts, education, and sciences” (as noted in her New York Times obituary), often anonymously supporting people, plants, and the causes she most cherished.

Today Mrs. Sweeney’s daughter Harriet Fraunfelter, who serves as an NTBG Trustee and on The Kampong’s Board of Governors, said her mother would be pleased with the direction The Kampong has gone. “She would be thrilled with what Craig [Director of The Kampong] is doing now, and with the quality of the horticulture,” Harriet said.

Furthermore, Mrs. Sweeney, who is remembered as a lifetime advocate for protecting plants and advancing education, forged deep ties with Harvard University through Dr. Barry Tomlinson and Dr. Dick Howard who taught over 20 years of tropical botany classes at The Kampong. Mrs. Sweeney’s unflagging commitment to tropical botany and education continues today as the National Tropical Botanical Garden partners with Florida International University to create the International Center for Tropical Botany at The Kampong. This new facility is planned to be built immediately adjacent to The Kampong in the years ahead, continuing the legacy of Dr. Fairchild and Mrs. Sweeney.

[1] In 1963 when Hawai‘i Senator Daniel Inouye introduced the original bill calling for the U.S. Congress to establish a new botanical garden in Hawai‘i, he had to make a concession to the Florida delegation which did not support the name National Tropical Botanical Garden, the result being the name “Pacific Tropical Botanical Garden” (1964-1988). With the addition of The Kampong, the Garden had a new opportunity to change its name “back” to National Tropical Botanical Garden as intended in the original bill.

Brother’s Keeper: Discovering Hibiscadelphus on West Maui

By Steve Perlman, Plant Extinction Prevention Program, Statewide Specialist

There we were, three botanists deep down a vertical slope in the remote mountains of West Maui, in the biologically rich Kaua‘ula Valley, preparing to conclude a long day of field work for the Plant Extinction Prevention (PEP) Program. It was nearly five o’clock and we were still a couple of hours’ hike away from our camp but taking one last look through his binoculars, my colleague Hank Oppenheimer pointed and said, “What’s that tree two ridges over?”

“It looks like Hibiscadelphus to me,” I answered. Although we were surrounded by cliffs and high peaks, Keahi Bustamente said he saw a way to reach the tree and so, overcome with the unexpected rush of excitement, we agreed to embark on the adventure.

An Incredible Discovery

After crossing two nearly vertical gulches, I waited for Keahi and Hank, so the three of us could enter the forest area together for what we were sure would be an incredible discovery. When I saw the fruit and Hank spotted the flowers, there was no doubt in our minds: we had discovered a new species of Hibiscadelphus.

While most people are familiar with commonly cultivated hibiscus, far fewer ever see Hawai‘i’s native hibiscus with flowers that range in color from red, pink, and white to orange and the bright yellow Hibiscus brackenridgei — Hawai‘i’s state flower.

Even more rare is the incredibly unique endemic genus Hibiscadelphus of which six of the seven named species are already extinct in the wild. Hawaiians call it hau kuahiwi meaning mountain hibiscus. Early 20th century botanist Joseph F. Rock first named the genus in 1911 for a species he worked with, naming it Hibiscadelphus — literally “brother of Hibiscus.”

Only one species — H. wilderianaus — represented by a single tree, had ever been found on East Maui and Hibiscadelphus was completely unknown on West Maui before we discovered this population of about 25 trees.

The Long Way Back

By the time we had collected flowers, fruit, seeds, and photographs, it was getting dark. We started up the cliffs and tried to return to camp by going straight up. Bad idea. We ended up using ropes and went a way we did not want to ever repeat. Fortunately, each of us carried head lamps, allowing us to make it back to camp by 9 p.m..

After our discovery, we decided to compare it with all known Hibiscadelphus in consultation with leading experts studying the Malvaceae family who confirmed it was indeed new to science. In subsequent field trips, our PEP team explored further and has since identified three sites populated by nearly 75 trees.

Hibiscadelphus stellatus

After considering a name for this plant, we decided on Hibiscadelphus stellatus. The Latin species name stellatus means star-shaped and alludes to the stellate hairs or pubescence. Stellatus also acknowledges the stellar (outstanding) beauty of the flower. The key differences between the West Maui Hibiscadelphus and its closest relative, H. wilderianus, are the dense white or tan stellate hairs on leaves, stems, bracts and larger purple colored flowers, yellow colored within. The flowers of Hibiscadelphus attract endemic honeycreeper birds whose bills match the decurved flowers, allowing the birds to drink the sweet nectar and cross-pollinate the flowers.

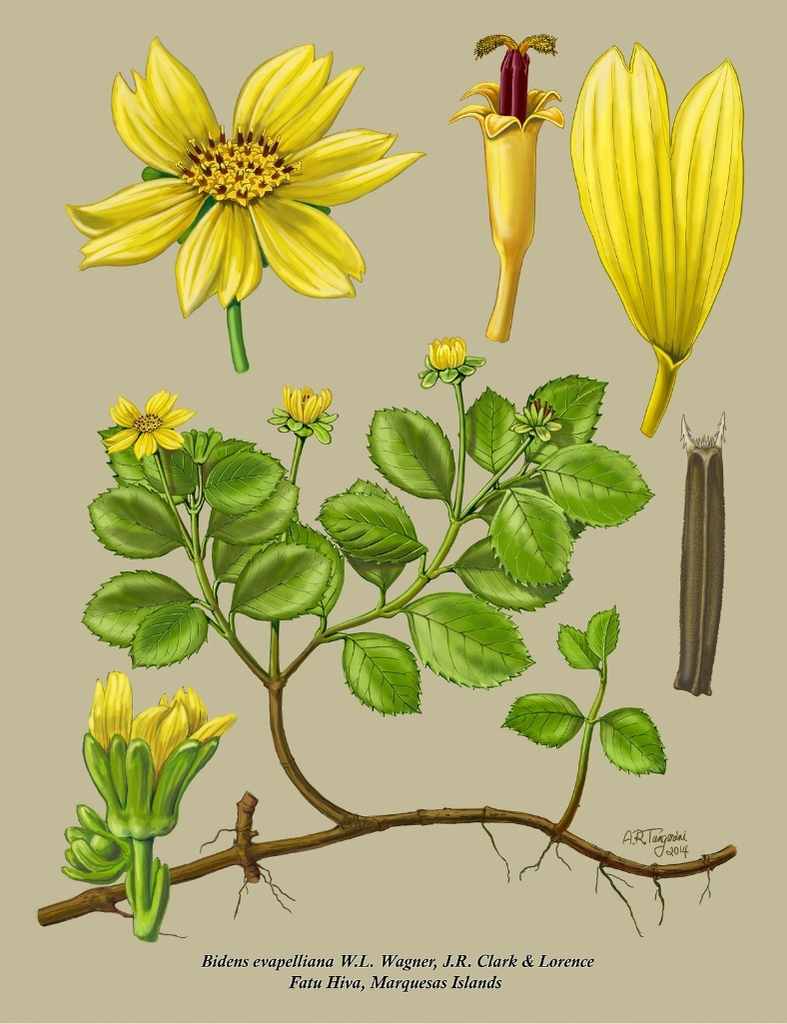

Following peer review and acceptance, our description of Hibiscadelphus stellatus was published in journal PhytoKeys 39: (pgs. 65-75) in 2014. The plant was also meticulously illustrated by Alice Tangerini, a staff illustrator at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, Department of Botany.

Preventing Plant Extinction Together

For those of us who work to save these unique plants, we see them as jewels of creation. For me personally, I’d like to think that all of us care about saving biodiversity because extinction truly is forever. This discovery, a great success for the PEP Program, is also a success for NTBG because together, we’re saving plants.

In 2014, Steve assumed the role of statewide specialist for PEP, concentrating on rough terrain field work on Kaua‘i and across the state. Steve is based at PEP’s Kaua‘i office located inside NTBG’s Botanical Research Center, allowing him and PEP staff to partner with NTBG. The PEP program’s Kaua‘i office has been housed at NTBG since its beginning as the goals of both are the same — to prevent plant extinction. Together NTBG and PEP locate, collect, and monitor Hawai‘i’s most endangered plants in the face of threats like introduced weeds, rats, feral ungulates (especially goats, pigs and deer), habitat loss, and disease. Among PEP’s goals are collecting seeds for long-term storage and growing endangered species in micropropagation tissue labs.

Currently, around 450 Hawaiian plant species are federally listed as endangered, far more than any other U.S. state. While more than 130 of the more than 1,350 species in the Hawaiian flora have gone extinct in the wild, Hawai‘i has experienced zero plant extinctions since the establishment of PEP in 2001. Today the PEP Program has botanists working on Kaua‘i, O‘ahu, Maui, Moloka‘i, Lāna‘i, and Hawai‘i Island. Learn more: http://www.pepphi.org/

About PEP

The Plant Extinction Prevention (PEP) Program, operates as a project of the Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit of the University of Hawai‘i. PEP focuses on conserving the rarest of rare plants —238 Hawaiian species with 50 or fewer known wild individuals. Research Biologist Steve Perlman, who has worked for and with NTBG since 1972, played a central role in the development of the PEP Program, even giving the program its name.

Kahanu Garden Safeguards Banana Heritage

By Mike Opgenorth, Director, Kahanu Garden and Preserve

Kahanu Garden and Preserve, in Hāna, Maui, is home to Pi‘ilanihale Heiau, a National Historic Landmark and the single largest archaeological structure in the Hawaiian Islands. Plant collections at this powerful Hawaiian place are largely those of ethnobotanical origin; in other words, plants that reflect the agricultural customs, lore, and uses within a culture. Most of the ethnobotanical plants at Kahanu Garden are Pacific Island and Hawaiian heritage plants.

Prominent among them is Kahanu Garden’s maia (banana) collection, which represents varieties bred from plants that were painstakingly transported across the Pacific. The collection includes many rare varieties that are valued as food, building materials, medicine, and for use in ceremonies such as the annual welcoming of makahiki, which recognizes the rising of the Makalii (Pleiades) into the heavens.

Canoe Plants

Prior to the 1778 arrival of Westerners in Hawaii, a wide variety of Polynesian-introduced “canoe plants” including bananas were planted in some of the most remote, and idyllic locations throughout the islands. These plantings were intended to provide food for travelers on long journeys, or even as sacred gardens reserved for a special purpose such as in times of political instability when one had to flee home for solitude in the forest. These bananas also were reserved for use as a kind of offering presented to alii (ruling chief) or as a highly regarded gift.

Unfortunately, since that time, many of these remote indigenous crop gardens have been overgrown by invasive species. With their disappearance come the loss of unique biological material and the stories of their origin. Those losses are akin to removing pieces of the puzzle of Hawai‘i’s early history.

In recognition of the threat of losing indigenous crop diversity, NTBG recently adopted a strategic goal to collect and curate all extant cultivars of Hawaiian canoe plants. The number of those early varieties is a fraction of what it once was, and research to verify each is ongoing. The current status of many of these rare varieties is debated and requires much more than simply placing a few new plants in the garden.

Meanwhile, for all the indigenous crop varieties that still exist, NTBG serves as a safe haven where they can be preserved and shared for future generations. The fact that most of East Maui is still free of the Banana Bunchy Top Virus (BBTV) is an important reason that Kahanu is a safe haven for these Hawaiian banana cultivars.

A Feast of Fruit

Walking through Kahanu Garden’s banana collection is a feast for the senses. Standing in rows, vigorous banana plants tower over a mixture of kalo (taro), awa (kava), and wauke (paper mulberry). Growing in multi-layered crop plantings alongside the bananas, the plants recreate a landscape of Hawai‘i’s ancestors where heavy bunches of fruit cascade from above in a multitudinous display of colors, shapes, and sizes.

Consider Popoulu Huamoa, the variety that first greets you with its enormous sausage-shaped fruits. Beside it stands Iholena Upehupehu with deep salmon-purple leaves. Then, perhaps the biggest showstopper of all, a rare Manini, the only traditional Hawaiian banana with all variegated leaves and fruit.

Each of these varieties is unique and reveals the diversity of Hawaiian bananas while underscoring the importance of NTBG’s collections. Bananas belong to the group of plants known as Zingiberales (gingers, heliconias, and related families), and NTBG is an official conservation center for the Heliconia Society International (HSI), which strives to conserve documented living collections of these plants.

With multiple locations in Hawaii, different NTBG gardens will be tasked with piloting different collections. Limahuli Garden on Kauai’s North Shore preserves the main collections of kalo, while McBryde Garden is home to the uala (sweet potato) collection, and Kahanu Garden is home to collections of maia (bananas) and ulu (breadfruit).

By protecting all extant cultivars of canoe plants within our gardens, NTBG continues to grow as an invaluable resource for researchers, cultural practitioners, and as a place to safeguard Hawai‘i’s ethnobotanical and cultural heritage. As demonstrated by NTBG’s Breadfruit Institute and the collection at Kahanu Garden, NTBG plays a vital role in advancing solutions to global hunger.

Banana Blindspot

Today bananas are the most widely consumed tropical fruit in the world and, as a result, don’t elicit the same sense of wonder that they did when first introduced to the United States at the World’s Fair in Philadelphia in 1876. Yet, as commonplace as bananas have become, it’s easy to forget it wasn’t always so. What is often overlooked — call it a “banana blindspot” — is how many varieties still exist and why they need protection.

Most commercially grown bananas are of the Cavendish group — varieties like Williams, Dwarf Chinese, and even Hawai‘i’s local favorite, the ‘Hawaiian Apple.’ The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates roughly 47 percent of global production is of the Cavendish group with more than 50 billion tons of bananas produced globally each year. In the United States and the European markets, Cavendish bananas virtually dominate the entire market.

So what is wrong with this picture? Imagine a single plant species represented by just one variety as the only thing growing for hundreds of miles. This type of agricultural system, driven by our demand to produce economies of scale, leaves little opportunity for diverse habitats and ecosystems to thrive.

With genetic uniformity in such large plantations, one disease can spread like a hot spark in dry tinder, completely destroying entire farms in one fatal swoop. To cite one example, a new Fusarium wilt strain called TR4 is currently an enormous threat to Cavendish banana production as it quickly spreads throughout the world.

When existing commercial varieties do not exhibit the resiliency to combat these types of new diseases, it is important that other banana varieties are available to preserve irreplaceable genetic diversity that can help feed the world.

How can we counter the negative impacts of large plantation agricultural system failures, the loss of major food crops, and the displacement of ecosystems? One answer can be found in Hawaii’s kupuna (elders) who share an important sentiment — nana i ke kumu (look to the source) — in addressing today’s complex problems. When considering how to preserve the irreplaceable diversity of Hawaiian canoe plants, in this case, bananas, NTBG will continue to look to the source as we document, collect, and protect the banana varieties that are an invaluable part of Hawaii’s cultural and botanical heritage.

Eye on Plants – Phyllostegia electra

Conservation Biologist Seana Walsh fondly recalls the scentless Hawaiian mint Phyllostegia electra not for its absent fragrance, but because it was the very first plant she collected on her first day of field work for NTBG.

Botanizing along with colleagues Steve Perlman and Merlin Edmonds, Seana brought seeds of the delicate P. electra back to the Garden’s Conservation and Horticulture Center where it was propagated and planted in the Montane Forest Display, allowing scientists to examine the rare plant without the expense and risk of undertaking an arduous journey.

Phyllostegia electra is endemic to the mesic and wet forests of Kauai and only rarely seen outside its habitat. Like other native Hawaiian plants, P. electra evolved in isolation and free of predators which is why it and Hawaii’s other 63 endemic mints lack the odorous oils that serve as a defense mechanism.

Critically Endangered

Furthermore, P. electra is assessed as Critically Endangered (CR) according to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species and a focal species for achieving conservation objectives outlined in the Hawai‘i Strategy for Plant Conservation. It is not, however, protected by the Endangered Species Act.

With less than 50 known wild individuals growing in 15 subpopulations, P. electra was added to the University of Hawaii’s Plant Extinction Prevention Program (PEPP) [see related side bar on page 6]. Since early 2017, NTBG and PEPP have worked together to collect seeds and cuttings from known individuals, and search potential P. electra habitat for more.

As part of an ongoing genetic population study, NTBG is collaborating with Chicago Botanic Garden to better understand diversity in this species. Increased diversity means a more vigorous, robust gene pool and a better chance of survival for this species which is threatened by feral pigs, goats, rats, and even slugs and snails.

Propagated seeds or cuttings are outplanted into appropriate, protected, and managed habitat like the Upper Limahuli Preserve on Kauai’s north shore.

Seed Storage

Meanwhile, Seed Bank and Laboratory Manager Dustin Wolkis is experimenting with the seeds to determine how they respond to drying and cooling which will inform optimal storage methods.

Phyllostegia electra fruits in the spring and cleaning seeds is a labor intensive process. After seeds are cleaned, Dustin tests initial exposure to liquid nitrogen to rapidly freeze seeds in order to avoid ice crystal formation (which can be lethal to cells) before transferring them into a -80°C freezer for long term storage. At this time, NTBG is the only facility in Hawai‘i testing liquid nitrogen for the cryopreservation of seeds.

A two-year grant from the Mohamed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund helps pay for field botanists like Seana to fly out to remote habitat to collect plant material and for supplies like liquid nitrogen. By testing seeds for optimal storage conditions, the chances of saving the species from extinction greatly improve.

Dustin says, “This research, combined with ongoing collection, will reduce extinction risk and aid in the species’ recovery.” Collection, propagation, and the seed storage trials for this scentless Hawaiian mint continue.

The Science of Art – Why Botanical Illustration Matters

Plant lovers inherently appreciate beauty. We marvel at the arc of woody stems, the gentle curl of a leaf, or the way sunlight penetrates flower petals to reveal unexpected colors. The observation of plants is visually captivating and intellectually instructive whether we are arranging flowers at the kitchen sink, examining a stately tree in a garden, or collecting the seeds of an endangered shrub.

When we admire plants online, the internet offers up a flurry of photos, videos, and images that we click through like an old-fashioned movie projector. Increasingly, technology allows us to manipulate, enhance, and improve images with a few mouse clicks to create “picture perfect” photos of flawless flowers and plants that “pop.” In doing so, however, we run the risk of overlooking the centuries-old tradition of botanical illustration.

Botanical Illustration at NTBG

But in the world of botany, scientists and students, collectors and curators not only still appreciate, but absolutely depend on hand-drawn illustrations, paintings, and other traditional plant renderings.

At NTBG, we greatly value the importance of preserving and using historical botanical artwork in books and print collections. At our Botanical Research Center on Kauai, The Sam and Mary Cooke Rare Book Room houses our botanical art collection, including a complete set of the Banks Florilegium. We also host botanical illustration workshops at The Kampong in Miami and at NTBG headquarters where we help foster and exhibit the art of the NTBG Florilegium Society.

In an attempt to underscore and explain its timeless beauty and scientific value, we’ve asked our staff and partners to share their thoughts on why botanical illustration matters.

Why Drawing Plants Matters

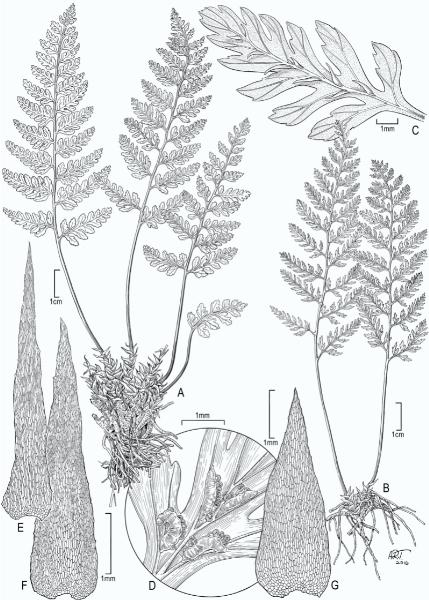

“Botanical illustration serves as a connection between art and science and, in fact, is firmly planted in each discipline. As an addition to herbaria, it provides a detailed description of the species, whether as a pen and ink illustration or a richly colored watercolor, highlighting and magnifying hidden details and presenting them in an easily understood visual format. The illustrations give life and a three dimensional quality that contrasts and compliments the dried plant specimens found in herbaria.” —Tim Flynn, NTBG Herbarium Collections Manager

Important for Plant Science

“Botanical illustration is an important aspect of plant science for a number of reasons. The illustrator emphasizes the important or diagnostic characters of a plant for the viewer. This is particularly true for pen-and-ink line drawings, which are generally used to illustrate or supplement descriptions of new plant species.

Indeed, the illustrator may see details that the botanist misses. Line drawings give the general aspect or habit of a plant, plus details of essential characters such as veins, pubescence or hairiness, flowers, fruit, and seeds that are magnified or shown in longitudinal or cross sections. These black and white line drawings may appear two-dimensional and flat, since they are usually drawn from dried, pressed herbarium specimens.

Illustration Preserves Plant Species

Another type of illustration is the florilegium style, usually done in watercolor or color pencil. This brings vibrant, lifelike color to the plant being illustrated and varies with each artist’s personal style. Details such as a close-up of the flowers or seed, a cross section of the fruit, a sketch of the habitat, growth habit of the plant, and even associated organisms such as herbivorous insects or pollinating birds or butterflies may be included in the illustration.

A botanical illustration can preserve a plant species, variety, or cultivar in books and journals almost in perpetuity, even if it goes extinct in the wild. Such was the case with a critically endangered Hawaiian endemic genus and species, Kanaloa kahoolawensis, first discovered and published only two decades ago but now known only from two plants in cultivation. Finally, illustrations can also help conservation efforts by creating public awareness and empathy for plants.”—Dr. David Lorence, NTBG Senior Research Botanist

“Explained simply, botanical illustrators and their works serve the scientist. They depict what a botanist describes, acting as the proofreader for the scientific description. Digital photography, although increasingly used, cannot make judgements about the intricacies of portraying the plant parts a scientist may wish to emphasize and a camera cannot reconstruct a lifelike botanical specimen from dried, pressed material.

Although illustrators now make greater use of digital research material and use the computer for digital illustrations, the thought process mediating that decision of every aspect of the illustration lives in the head of the illustrator. Whether pen and ink, pencil, watercolor, or the stylus on a drawing monitor, the tools only move at the discretion of the illustrator.

Historically, the illustration process follows the language of the scientist. Illustrators adapt media, presentation, and drawing styles to serve with current trends in scientific writing and to facilitate documentation of the scientific literature. However, the illustrator also has an eye for the aesthetics of botanical illustration, knowing that a drawing must capture the interest of the viewer to be a viable form of communication. Attention to accuracy is important, but excellence of style and technique used is also primary for an illustration to endure as a work of art and science.” —Alice Tangerini, Staff Illustrator at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, Department of Botany

I don’t simply copy how a plant looks but must explain plants through my drawing.

Wendy Hollender, Botanical Illustrator, Instructor, and Author

“The aesthetic beauty of botanical illustration has fascinated and inspired people for centuries but beyond its visual appeal, botanical drawings help identify and understand plants in a timeless manner. Its original purpose was to aid in plant identification for medicinal and culinary uses. Over the centuries, as the discipline developed, botanical illustration has proven itself invaluable in identifying newly discovered plants.

Carl Linnaeus, known as the father of modern taxonomy, and botanical illustrator Georg Dionysius Ehret, famously used botanical illustration to classify and describe the structure of plants. In the early nineteenth century, Belgian painter and botanist Pierre-Joseph Redouté captured the magnificent plants in the garden of Napoleon Bonaparte and Empress Joséphine de Beauharnais.

As a botanical illustrator, I don’t simply copy how a plant looks but must explain plants through my drawing. Botanical illustrations must reveal a plant’s morphological structure such as the arrangement of reproductive parts, leaves, and stems with a three dimensional quality.

Botanical illustration attracts and compels us. A pretty flower is not just a pretty flower, it has a specific purpose: to attract a pollinator. The flower’s visual appeal comes from colorful markings and its enticing scent lures the pollinator to the nectar within.

The scientific study of plants is essential for dealing with environmental changes, containing the spread of invasive plants, and saving endangered species, all issues addressed through botanical illustration. Although science has focused mostly on black and white pen and ink drawings, color can be used as well provided the artist capture a plant’s important structural elements.

What I find most alluring about botanical art is its seductive quality — drawing me in, feeding my desire to linger inside the mysterious center of the flower, looking through its leaves to another flower like an insect fluttering from blossom to blossom. Imbued with beauty and color, the botanical illustration seduces and attracts.”

—Wendy Hollender, Botanical Illustrator, Instructor, and Author

A botanical artist can tell the whole story of the plant

Sarah Roche, Botanical Artist, Teacher, and Education Director

“A botanical illustration is not primarily judged on its artistic beauty, but on its scientific accuracy. It must portray a plant with enough precision and detail for it to be recognized and distinguished from another species. The beauty of the drawing or painting is secondary to its scientific accuracy, but, in the hands of a talented botanical artist the illustration can go far beyond its scientific requirements.

Photography can help inform but only drawing can emphasize the detail. A botanical artist can tell the whole story of the plant: what it looks like at any stage of its life cycle and in every season. Important details can be added at different magnifications so that the important features of the subject, not shown simultaneously in nature, can be displayed together to tell the whole story of the plant.”

—Sarah Roche, Botanical Artist, Teacher, and Education Director, Wellesley College Botanic Garden

The Art of Plant form and Evolution

“The tradition and practice of incorporating botanical illustration, watercolor, and other media into the process of describing new plant species continues to be a rich and profound contribution to the science of botany. For many, the written diagnosis or description of a species, although exacting and artistic in its own right, is often quite dull and lifeless. For me, time and time again, it is the manuscript’s botanical art contribution that brings to life the uniqueness and sublime diversity of the species being described.

The botanical art itself becomes a lens for the viewer to see deeper into the divine artistry of a plant’s form and evolution, which in most cases helps define the key parts that render the species new to science. It is true that well-taken photographs could suffice in displaying the unique qualities of the plant being studied, but for many it is the botanical artist’s rendition that is preferred and brings us closer to the subject.

What attracts us to botanical art? Perhaps it is the combination of careful attention to detail, along with the arduous internal human process of transforming a species’ visual likeness and character through the filter of mind and soul. Meticulously stirred together with the artist’s love for nature, the image flows through hands, communicating the importance and beauty of an ancient creation only newly described.” —Ken Wood, NTBG Research Biologist

This article was originally published in The Bulletin of the National Tropical Botanical Garden, Fall/Winter 2017

.svg)