Around the globe, biological scientists are racing to discover and document species before they are lost forever. The herbarium collection at National Tropical Botanical Garden contains nearly 90,000 preserved plant specimens, some dating back to 1837. It provides critical resources for biodiversity, ecological, and evolutionary research aimed at saving species. You can help us protect it. Donate to the Growing Green campaign today. Your gift will help us reach our energy efficiency goals and improve our Botanical Research Center to preserve this precious collection for generations to come.

It’s 2021 and scientists around the globe are working to document new species every day. It isn’t easy to believe in a world as connected as ours, but studies estimate that there are up to 15 million species living on Earth, only 2 million of which are known to science. This means we may share our planet, ecosystem, and maybe even our backyards with a multitude of unknown species!

At current rates, it could take centuries for scientists to discover and describe life on our planet in its entirety. Even if it is possible to do so, biodiversity is declining and disappearing at rates not seen before in human history. Botanical gardens and scientific research institutions like NTBG have an essential role to play in making a difference and stemming the tide of extinction.

“Collections of pressed, dried, and accurately identified plant specimens (herbaria) are the foundation for all studies of plant diversity and evolution,” said David Lorence, Senior Research Botanist. “Like other natural history collections, herbaria are essential resources for the classification and the study of biodiversity. If we don’t know the names of species, we can’t conserve them,” he continued.

“Collections of pressed, dried, and accurately identified plant specimens (herbaria) are the foundation for all studies of plant diversity and evolution.”

– David Lorence, NTBG Senior Research Botanist

The Herbarium collection at NTBG includes:

It is a unique reference of natural history and a resource for researchers at the National Tropical Botanical Garden and worldwide. The herbarium was established in 1971 as a record of the local flora when the Garden began operations. The collections have been built over more than 50 years through field expeditions and exchanges with other herbaria worldwide. NTBG has a very active collecting program adding 1-2 thousand new specimens per year, primarily from Hawaii and the Pacific.

As habitats disappear and our changing climate threatens all aspects of life on Earth, documenting biodiversity in herbarium collections will become increasingly important. So, how are plants entered into the permanent biological record? It starts with a discovery in the wild.

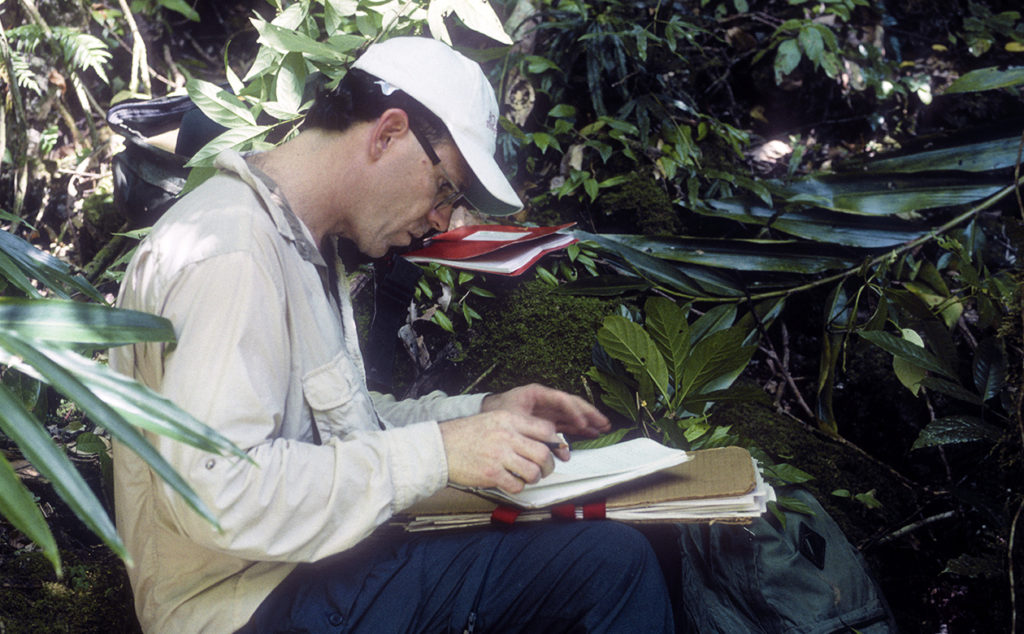

When a new plant is discovered, NTBG scientists start describing the species and preparing it for preservation in the herbarium. Scientists take field notes on the habitat and surrounding vegetation, plot GPS points and collect, press, and dry the specimens. Photographs are taken to supplement the preserved specimens, and leaf material is obtained for later molecular phylogenetic studies using DNA.

The dried specimens from the field are freeze-fumigated to remove contaminants and pests before storage. Beetles and other insects can consume and destroy herbarium specimens if they are accidentally admitted into the collection. Once the new samples have been fumigated, they are mounted on archival paper with their labels, then barcoded, imaged, and incorporated into the NTBG collection. Duplicate labeled and identified specimens are shared with herbaria of collaborating institutions, including the country of origin where the species was discovered.

Collecting plant material and entering a new species into the record is time-consuming and labor-intensive. It is often made more challenging by lack of funding, permitting, and regulations.

“Successful fieldwork requires careful planning, funding, and collaboration, especially if it takes place outside the USA,” said Lorence. “First, it is important to establish contacts and partnerships with local organizations and individuals in the host country, for these are essential for obtaining access to collecting areas and collecting permits. Training and capacity building of host country partners is also an important aspect of fieldwork. We learn as much from them as they do from us,” he remarked.

Proper equipment is also an essential part of plant discovery and documentation. Native vegetation has disappeared from most lowland areas in the tropics, particularly on islands. Most intact native vegetation is confined to mountain slopes and summits, requiring strenuous hikes carrying collecting equipment, water, and supplies.

Exploring and documenting the plant life of poorly known areas with herbarium specimens and making conservation recommendations are critical steps towards producing a region’s written flora. NTBG is dedicated to tropical plant discovery, research, and conservation and recently completed the Flora of the Marquesas, a collaboration between NTBG, the Smithsonian Institution, Délégation á la Recherche de la Polynésie Française, and others that was decades in the making.

The two-volume book offers a complete account of all the plants found in the Marquesas. Of the 826 vascular plant species recorded, 331 species are native including 100 ferns and lycophytes, with the remainder being human-introduced. Nearly half of the native flora (47%) is endemic to the Marquesas.

“Knowing that specimens I’ve collected have contributed to a better understanding of the flora of a particular area is particularly gratifying.”

– Tim Flynn, NTBG Herbarium Curator

“Knowing that specimens I’ve collected have contributed to a better understanding of the flora of a particular area is particularly gratifying,” said Tim Flynn, NTBG Herbarium Curator. “The collections I’m making today aren’t necessarily for me or this time, but for future generations,” he concluded.

Herbarium Collections like NTBG’s fill in the pages of the catalog of life on Earth and can help us respond to environmental changes and threats from habitat loss and climate change. Our collection is primarily comprised of plants of the Pacific, but many other research institutions and organizations are working to document and assess species on a global scale.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species is the world’s most comprehensive inventory of the conservation status of biological species. It helps scientists evaluate the risk of extinction for thousands of known species of plants, animals, and fungi and is an essential tool for conservation management. On March 25, 2021, the IUCN released an updated Red List which includes 134,425 assessed species from around the world. 54,127 of them are plants, each given a rank in one of nine categories from species of “least concern” to “extinct.” 28 percent of the now assessed species are recognized as “threatened”. This recent update also includes assessments of all 255 Kauai single-island endemic vascular plants completed last year in an effort led by NTBG. By completing the Red List assessments for all of Kauai’s endemic plants, NTBG has verified that 10 percent are already extinct and the remaining 90 percent all classified as “threatened” according to the internationally recognized IUCN Red List criteria highlighting the scale and urgency of plant conservation in Hawaii.

As a member of the IUCN Species Survival Commission for Hawaii, NTBG uses our Herbarium Collection data to assess the conservation status of Hawaii’s flora. Information about distribution range and population size over time determine if a species or taxon is considered a species of least concern, near threatened, threatened, endangered, or critically endangered.

NTBG Herbarium staff and volunteers are currently working on digitizing the collection. As of 2021, approximately 65% of the records have been digitized and made searchable online.