Category: Limahuli

How NTBG gardens fight invasive species in Hawaii

February is Invasive Species Awareness Month in Hawaii, a time to consider the threat posed to Hawaii’s unique and irreplaceable flora and fauna. The Hawaiian Islands are famous around the world for the high level of endemism—plants and animals found only in a specific location and nowhere else. Of Hawaii’s roughly 1,300 native plants, 90% of them are endemic to the Hawaiian Islands. Many are single-island endemics, for example, found only on Kauai or only on Maui. Others are restricted to a single valley, ridge, or other small geographic area.

Throughout the last century or two, the number of humans and introduced plants and animals have rapidly and dramatically altered ecosystems and affected species to the point that 85% of Hawaii’s land has lost its native flora.

Invasive species continue to take an enormous toll on Hawaii’s natural world. Everything from Himalayan ginger and guinea grass to Coqui frogs, little fire ants, feral ungulates, rats, slugs, and domesticated animals are over-running Hawaii’s vulnerable native flora and fauna.

NTBG is a not-for-profit organization dedicated to plant discovery, scientific research, conservation, and education. Our network of five botanical gardens and four preserves serve as living laboratories and our team of staff and scientists perform an important role in the fight against the damaging effects of invasive species in our communities and native ecosystems. Our efforts to slow and stop the spread of invasive species begin at home in our gardens and preserves throughout Hawaii and Florida, and make a global impact.

Kauai Island (McBryde, Allerton & Limahuli Gardens)

Our extensive collections of palms, Rubiaceae, Heliconias, orchids, and many others have been wild-collected by botanists and biologists from throughout tropical regions around the world and transported to our gardens to research, cultivate and thrive. Living collections staff and volunteers monitor our collections regularly to identify species for invasive tendencies to ensure these introduced plants do not become harmful to the surrounding environment. Once identified as invasive, species are deaccessioned and removed.

Threats from outside NTBG’s Living Collections also exist. Invasive species often make their own way into our gardens and it can often be hard to recognize their invasive tendencies among the veritable botanical ark of tropical flora. The Kauai Invasive Species Committee (KISC) assists with monitoring the gardens and have so far helped to identify and remove two taxa that were invasive to Lawai Valley. These taxa have been added to their database for further monitoring.

Maui Island (Kahanu Garden)

Invasive species like nutsedge, inkberry, turkeyberry, honohono, and African tulip trees present an ever-growing threat to Kahanu Garden’s collection of Hawaiian and Pacific heritage and agricultural plants as well as the Piilanihale Heiau cultural site. Each year Kahanu Garden staff remove thousands of young plants that arrive as airborne seeds and quickly set deep roots, leave seed banks in the soil, and require months or years of active management. This requires an ever increasing commitment by staff and volunteers to keep the aggressive invasive plants in check.

In the Field

In addition to KISC, NTBG scientists work with agencies like Hawaii Department of Agriculture and the Department of Land and Natural Resources to provide field observations and reference collections that can be used for specimen identification as well providing population and occurrence information on invasive species.

When our botanists are in the field and observe an invasive plant they’ve never seen on the island before, they document the observation and notify the KISC Early Detection Program. These early detections can mean the prevention of a new invasive species on the island from becoming established.

Conservation of threatened and endangered flora is our highest priority, but stemming the spread of invasive species and the threats they pose to native ecosystems is a big job we can’t do alone. In addition to our team, we rely on dedicated volunteers and curious visitors to help save plants and people. You can help by planning a visit to an NTBG garden, volunteering your time, or making a donation.

Want to make a difference in your own community? Learn more about your native ecosystem and the plants that keep it healthy and thriving. Don’t miss our upcoming webinar spotlighting the fight against invasive species and efforts to propagate native plants for horticulture trade. Register today.

Discovering new forms of life in the Limahuli Preserve

Little Wing: Discovering new forms of life in the Limahuli Preserve

By Jon Letman, Editor

The Hawaiian Islands are often associated with big, dramatic natural events (volcanic eruptions, powerful ocean swells) and large, complex ecosystems (dense tropical forests, dynamic coastlines), but it’s Hawaii’s earliest, smallest, least known creatures that offer one of the most important lessons about evolution, diversity, and interdependence.

Hawaii is home to a genus of micromoth called Philodoria which is believed to have first reached the Hawaiian Islands 21 million years ago (some 8 million years before Hawaiʻi’s largest plant clade, the Lobeliads). Like the larvae of some beetle and fly species, Philodoria are leaf miners. They’re also extremely small — about as long and as thick as a human eyelash.

When the tiny moth lands on the leaf of its host plant, it lays eggs which produce microscopic caterpillars that burrow through the leaf, forming tiny tunnels and caverns as they eat their way through the tissue of their thin, green home. There they grow into larvae safely sheltered from predators like parasitoid wasps which are known to use Philodoria larvae as a host.

After several weeks, the caterpillar grows until it pupates, emerging from the leaf in a cocoon before metamorphosizing into a moth. The whole process takes up to six weeks.

Survival of the Philodoria, which are endemic to Hawaii, depends on the moth-host plant relationship. If the host plant goes extinct, it stands within reason that the moths that depend on them will disappear too.

Barely known, rarely seen

Earlier this year, researchers from Osaka Prefecture University and the Florida Museum of Natural History (University of Florida) published a monograph (in depth study) with names, descriptions, and the conservation status of 13 new Philodoria species and their host plants. In total, researchers confirmed 51 Philodoria species, many of which hadn’t been seen in over a century, and 13 of which were new to science.

Among the newly described moths, Philodoria limahuliensis, is known from a single location in the Upper Limahuli Preserve. Biologist Dr. Chris Johns, a co-author of the paper, first saw the moth in 2016. Johns, a self-described micromoth enthusiast, says even this tiny creature plays an important role in the ecosystems they inhabit.

Studying Philodoria can help us understand many other forms of life, including our own, says Johns. “Philodoria moths can teach us a lot of things about life on this planet and evolution.”

When Johns teamed up with entomologist Dr. Akito Kawahara at the University of Florida in 2013, Philodoria hadn’t been studied closely in over a century and their conservation status was poorly understood. Johns, who had previously done conservation work in Hawaiʻi, jumped at the chance to join Kawahara for what would be a five-year study searching for some of the world’s smallest moths inside of the world’s rarest plants.

Over the course of six trips to six Hawaiian islands, Johns partnered with local scientists to search for Philodoria living among host plants including ohia (Metrosideros spp.), mamaki (Pipiturus spp.), and Hesperomannia, an extremely rare native member of the sunflower family. As a genus, Philodoria are diverse feeders though they tend to develop a very specific host plant relationship. One species lives among Wollastonia integrifolia, a coastal plant, while another lives within the greenswords (Argyroxiphium grayanum) of west Maui’s high elevation bogs where it was described as Philodoria wilkesiela by English entomologist Lord Thomas de Grey Walsingham in 1907. Johns found the same moth in that exact location in 2013. Philodoria’s historical range has been well-documented, Johns said, but it was difficult to find intact habitat that hadn’t been developed or entirely replaced by invasive species.

In 2015, based on Kawahara’s past collaboration with NTBG staff, Johns was introduced to then-NTBG field collector Natalia Tangalin, from whom he learned of known leaf miners suspected to be Philodoria in the Limahuli Valley. That year Johns and Tangalin helicoptered to a weatherport (in the Upper Limahuli Preserve to provide shelter for multi-day fieldwork) in the Upper Limahuli Preserve. Based on a hunch from Tangalin, they hiked down to a place where a small stream flows into a waterfall. Just above that spot, a lone shrub — Hibiscus waimeae subsp. hannerae — grew out of a sidewall in the stream. There they collected ten moths which Johns believes were unique to the location and to date is the only known habitat of what has been named Philodoria limahuliensis. Johns says P. limahuliensis is one of the rarer species but a second Philodoria species was found in Limahuli Valley living with its host ohia (Metrosideros sp.).

Why does it matter?

Some might question the significance of finding a tiny moth on a Critically Endangered plant in the back of a remote valley. Johns explains how such a discovery sheds light on the origin and age of organisms in Hawaii, a place that has informed much of our scientific understanding of evolution on islands. Philodoria may be the oldest extant lineage in the archipelago. “As far as things that remain alive in Hawaii today, Philodoria seems to be one of the first to get here,” Johns says.

And because, like the Galapagos, Hawaii is a storied natural laboratory for evolution, identifying a new micromoth found nowhere else on earth opens a new chapter of scientific inquiry and can address the same questions asked about other organisms, offering a new perspective and more comprehensive understanding of evolution and life on earth.

To study an insect as small as Philodoria, scientists must go to great lengths to identify and understand how species are related to one another. One method of identification is a morphological examination of the genitalia of each species which is challenging given the moth’s size. Another technique is the molecular analysis of tissue to compare DNA among differing species.

Using phylogenetics and a technique called ancestral reconstruction (DNA analysis to understand how species are related to one another), Philodoria researchers have gained new insights to what ancient moths might have been feeding on when they inhabited now sunken Hawaiian Islands that predated the islands we know today. Johns says it’s likely those ancient host plants belonged to Ebenaceae, Malvaceae, and Primulaceae. “That paints a really interesting picture of something we didn’t know before about this place,” Johns says.

A treasure trove of discovery

Even for the non-scientist, Johns says people are drawn to anything that creates a deeper, more complex picture of a place revered for its natural beauty. “What is it that comprises that natural history?” he asks. “It’s biodiversity. Who doesn’t love a new angle to a beloved story or character?”

The discovery of Philodoria limahuliensis near a small waterway that feeds into the Limahuli Stream underscores the importance of protecting and studying this pristine riparian habitat. The unique conditions found along the stream led to an NTBG-led project to restore the health and function of the stream. Selective tree trimming, outplanting, and extensive monitoring are expected to benefit native flora and fauna while helping preserve whole-ecosystem biodiversity in the Limahuli Valley.

Having found and identified Philodoria limahuliensis in the Limahuli Valley, Johns was elated to have had the chance to work in a native forest that remains largely intact and relatively weed-free. He calls Limahuli “among the very best of privately held land with robust environmental protection” in Hawaii.

“NTBG has something really, really, really special,” Johns says. “In terms of moth diversity and the potential for future discovery and protection… Limahuli is one of the best places. I think the work that’s being done there is top notch.”

Uala – Hawaiian Sweet Potato

By Mike DeMotta, Curator of Living Collections

“He ‘uala ka ‘ai ho’ola koke i ka wi” – Sweet potato is the food that quickly restores health after famine

The first Hawaiian voyagers arrived in the Hawaiian Islands with approximately two dozen plants that were important enough to earn space on the crowded outrigger canoes used to cross the ocean. These ‘canoe plants,’ as they are known, were vital for providing food, fiber, medicine, and more. Many of these plants had multiple uses. Three were essential staple food crops — kalo (taro), ulu (breadfruit), and uala (Hawaiian sweet potato).

Easily propagated and grown from live cuttings or slips, uala (Ipomoea batatas) was widely cultivated on all the islands. Many communities in Hawaii’s driest areas placed great value on uala and were able to produce enough of the starchy vegetable to sustain large populations by strategically planting it during the rainy winter months and keeping it stored underground for some time after the rains had ended.

Over many generations, mahiai (Hawaiian farmers), who understood the importance of crop diversity, developed many different varieties. They cultivated these hearty, tuberous roots, protecting against total loss of any given variety and building resilience in the event of changing weather patterns or other environmental instability.

As a staple food, uala is an excellent source of vitamin C, beta carotene, potassium, protein, and minerals. The unevenly-shaped Hawaiian sweet potato is valued as a life-preserving crop, but the shoots and young leaves (called palula in Hawaiian), are also cooked and eaten. Offering great flexibility in its preparation, uala can be cooked in the same ways as other potatoes. My favorite way to enjoy uala is steamed in an imu (traditional Hawaiian underground oven). Like kalo, uala can also be mashed into a soft poi which has the consistency of thick pudding and is eaten with fish. Uala poi ferments quickly and so it must be consumed within a day or two. Grated uala cooked with coconut milk is called palau and enjoyed as a special treat.

Today there are about 24 different varieties of Hawaiian uala. Each has a distinctive leaf shape and colors of skin and flesh that range from orange and red to white. The variety Eleele literally means ‘black’ and is named for its very dark stems. Huamoa (‘chicken egg’) is a smallish, egg-shaped tuber. Inside, its darker yellow center is reminiscent of an egg yolk. Palaai (literally: ‘fat’) refers to the size of the large tubers. Piko (‘navel’) is recognized by its deeply-lobed leaves.

Mike DeMotta Inspects uala variety papaa kowahi growing outside the nursery.

Like other multi-use edible canoe plants, many uala have medicinal value. One example of uala’s medicinal use was in the concoction apu, a drink with many ingredients, but primarily made with uala. Apu has been traditionally prepared for women to be taken soon after childbirth to facilitate healing.

NTBG currently has about 20 uala varieties in our collections growing at our south shore Conservation and Horticulture Center and at Limahuli Garden on Kauai’s north shore and Kahanu Garden on Maui. We maintain all varieties within our nursery because of the challenges of growing uala in the field, namely the tenacious feral pigs who always seem to know when uala is ready to harvest. If we don’t get to them first, the pigs will complete their own harvest and never fail to eat everything, destroying all stems and leaves as they go. Growing a backup collection safely inside our nursery, helps us ensure we preserve these irreplaceable varieties.

At NTBG, we have a strategic objective to maintain collections of important Hawaiian canoe plants within our gardens. Heirloom or heritage varieties of canoe plants that are not grown commercially tend to become less common. Each named variety of canoe plant holds great importance in Hawaiian culture, whether identified in ancient legends or for its value as food and medicine. Preserving these varieties, cultivated over many generations, and the names ascribed to each, is equally important. As a key component of Hawaiian language and culture, we must remember these names which provide connections to Hawaii’s ancestors. The same uala we grow today can be traced back many generations to Hawaiian farmers of long ago, providing us with essential sources of food, medicine, and beauty, and living links to an ancient past.

The UN General Assembly has designated 2021 as the International Year of Fruits and Vegetables. The campaign provides an opportunity to increase awareness of the importance of fruits and vegetables to health, nutrition, food security, and UN Sustainable Development Goals.

NTBG completes Red List catalogue of endemic plants

NAPALI — Researchers with the National Tropical Botanical Garden were devastated when the last known wild member of the endemic flowering plant Hibiscadelphus woodii was found dead in the Kalalau Valley in 2011.

The plant only grows along the sheer cliffs of Kaua‘i and had only been discovered a few years earlier, in 1991, when new rope climbing techniques allowed for further exploration of the extremely rugged territory.

But, in 2016, the two more individual H. woodii plants were re-discovered using another new technology — drones.

Read the entire article at: https://www.thegardenisland.com/2021/04/19/hawaii-news/ntbg-completes-red-list-catalogue-of-endemic-plants/

Finding Climate Solutions with Ancient Knowledge and New Technology

On March 11, 2021, thick bands of heavy rain stretched across the Hawaiian Islands. While wet weather isn’t uncommon in the state this time of year, rainfall rates of more than 3 inches per hour certainly are. On the North Shore of Oahu, the storm caused catastrophic flooding and forced evacuations. On Maui, the intense rainfall washed out bridges, dams and damaged homes. On Kauai, landslides closed Kuhio highway in both directions at Hanalei; an area hit hard by the record-breaking rain bomb of 2018. All of the National Tropical Botanical Garden locations in Hawaii were closed, and some suffered damage to infrastructure and living collections.

Unfortunately, this kind of story isn’t unique to Hawaii. The climate is changing all around the world. Climate models project that tropical regions worldwide will experience more significant swings in temperature and rainfall, prolonged droughts, and a more substantial threat from tropical storms and cyclones.

How is Climate Change affecting the Hawaiian Islands, and What Can We Do?

“Climate change affects nearly every aspect of the human-natural ecosystems in the Hawaiian Islands,” says Dr. Uma Nagendra, Conservation Operations Manager and Ecologist at NTBG’s Limahuli Garden and Preserve. “Rising sea levels threaten roadways, houses, and coastal farmlands as well as endangered native lowland waterbirds. Increasing temperatures and droughts threaten local food security. On Kauai, we have seen firsthand how landslides, powerful storms, and wildfires can isolate and devastate entire communities and ecosystems,” she continued.

“Climate change affects nearly every aspect of the human-natural ecosystems in the Hawaiian Islands”

In April 2018, a massive storm dropped 50 inches of rain in 24-hours on Kauai’s North Shore, setting a new U.S. rainfall record. Streams overflowed, homes and highways washed away, and many large-scale landslides buried vast swaths of forest, destroying native plant habitat. Cliffsides were left barren, and exposed soil offered an open invitation to invasive weeds that don’t provide the same ecosystem services as native forests because many fast-growing invasive plants are shallow-rooted, which can leave the landscape vulnerable to further erosion.

After this record-breaking event, NTBG scientists and conservation professionals returned to the field and the lab to apply ancient knowledge, new science and technology to save plants and continue to bring local and global climate solutions into focus.

Learning from the Past

“The most important lessons we can learn from the past are how to adapt and be resilient as the world changes,” says Dr. Nagendra. “Part of that is taking care of the ecosystems that sustain us with fresh water, stable land, and food. During the 2018 flood, we saw thousand-year-old structures withstand heavy flooding that infrastructure from the 1970s couldn’t handle,” she remarked.

To build resiliency and protect ecosystems from the unpredictability of climate change, threatened and endangered native plants must survive in botanical gardens and their natural habitats. The Limahuli Valley is the second most biodiverse valley in Hawaii, making it the ideal location for NTBG’s watershed-based conservation program at Limahuli Garden and Preserve.

“The most important lessons we can learn from the past are how to adapt and be resilient as the world changes.”

The biocultural conservation program at NTBG’s Limahuli Garden collaborates with land stewards in the neighboring valleys to restore health and function to the social-ecological system that native Hawaiians have sustainably managed for more than 1,000 years. The ahupuaa system provides philosophies and practices for maintaining biodiversity, ensuring forest health, protecting stream integrity, creating fertile agricultural fields, promoting an abundant near-shore fishery from mauka to makai (mountain to ocean), and acknowledges that humans are part of the ecosystem.

New Solutions Take Flight

National Tropical Botanical Garden has a long history of plant exploration and discovery. Nearly 90% of Hawaiian plants don’t grow anywhere else on Earth and are particularly susceptible to competition from invasive species and climate change because they evolved in isolation. Since the mid-1970s, NTBG botanists have navigated, climbed, and rappelled challenging terrain to hand-pollinate and collect material, including seeds, from rare plants.

While NTBG botanists still work in the field, the addition of drone technology has allowed them to survey previously inaccessible areas and find new populations of rare plants – some thought to be already extinct in the wild. “In Hawaii, we are working as quickly as possible to collect, store and propagate rare plants in case suitable habitat disappears,” says Ben Nyberg, NTBG GIS specialist and drone pilot. “We are developing drone systems that can be applied by conservationists around the world to combat climate change in a number of ways, from survey to collection to reintroduction,” he continued.

Documenting and collecting plant material is one step in the conservation process. Once rare plant populations are discovered and seeds collected, NTBG and partners must work together to store and propagate the plants safely.

We are developing drone systems that can be applied by conservationists around the world to combat climate change in a number of ways, from survey to collection to reintroduction.”

Banking on Plants

Seed banking is a vital ex-situ or off-site conservation practice that helps protect plants from climate change, invasive species, and habitat loss. The NTBG Seed Bank and Laboratory currently store more than 15 million seeds from 533 native Hawaiian taxa. To store seeds wild-collected from native plants in the Limahuli preserve or remote cliffsides, seeds first must be meticulously cleaned to remove all fruit remnants. Once cleaned, information about when and where biologists collected the seed is recorded in NTBG databases, and research is conducted to determine if and how they can be stored long-term.

“Back in the early 1990s, we thought that because of our geographic location in the tropics, seeds of most species would not be able to be conserved using conventional storage methods,” says Dustin Wolkis, NTBG Seed Bank and Laboratory Manager. “Thanks to our collaboration with the Hawaii Seed Bank Partnership and other institutions, we have been able to conduct long-term monitoring and have found exactly the opposite,” he noted.

With more than 30 years of storage and viability data, NTBG and seed banking partner institutions can better understand trends and predict the storage behavior and viability of rare seeds giving new hope to many of Hawaii’s rare and endangered species.

“Back in the early 1990s, we thought that because of our geographic location in the tropics, seeds of most species would not be able to be conserved using conventional storage methods. We have been able to conduct long-term monitoring and have found exactly the opposite.”

Bringing It All Together

At the intersection of ancient knowledge, new technology, and seed science sits an exciting new research project that could be a game-changer for Hawaii’s endangered plants. NTBG conservation staff at Limahuli Garden are currently investigating the use of drone technology as a means of revegetating landslide areas on Kauai. “The extreme rain and numerous landslides we have already seen on Kauai are exactly what we expect to see from climate change,” said Dr. Nagendra. “Conservation staff at Limahuli are working with Ben and the drone program to develop ways of using drones to distribute seeds and revegetate exposed soil with native plants after landslide events. We’re currently using seed trays to test the idea and see if it’s viable,” she continued.

In addition to the possibility of revegetating with drones, ongoing research with DeLeaves and the University of Sherbrooke in Quebec is aimed at customizing drone sampling mechanisms to remotely collect plant material such as seeds or cuttings, and reach plant populations on steep or rocky cliffsides that have been largely unreachable. “Covid certainly delayed our field tests,” says Ben Nyberg, “but we have been able to collaborate and develop the robotics remotely. Field trials have been scheduled for later this summer and we are excited to get to work.”

Growing Green

Plants are one of our best defenses against our changing climate. They are the foundation of healthy ecosystems and can increase climate stability by offsetting temperature, moisture, and greenhouse gas fluctuations. From ancient knowledge to field surveys and seed storage, National Tropical Botanical Garden works at every level to discover solutions and save plants. You can help by. Visit our support page to see how you can get involved.

Plant Hunters Secure Biodiversity Hotspots

Looking to the Past to Protect Flora of the Future

To protect the food of the future, humans must learn from the past. A secluded garden in Florida preserves a 19th-century culinary curator’s tall tales and botanical introductions, while modern-day NTBG plant hunters in Hawaii use advanced technology to document and save species in biodiversity hotspots. With your help, NTBG is stemming the tide of plant loss and food insecurity. When you donate to the National Tropical Botanical Garden, you’re a part of this critical work that keeps our plants and our planet healthy.

It’s hard to imagine in today’s social media-induced foodie frenzy that the American diet has been anything other than a cultural melting pot of culinary curiosities. However, as Author Daniel Stone writes in his 2018 novel, The Food Explorer: The True Adventures of the Globe Trotting Botanist Who Transformed What America Eats, the same way immigrants came to our shores, so too did our food.

Before the 20th century, much of what America ate was meat, seafood, leafy greens, beans, grains, and squash – nutritious and hearty, but hardly the colorful, flavorful fruits and vegetables easily acquired from grocery store shelves and farmers markets today. Surprisingly, we have one adventurous, botanizing plant hunter to thank for most of the introduced tropical fruit, nuts, and grains that have become prominent parts of the American diet, and he is closely connected to NTBG.

David Fairchild was one of the world’s leading plant collectors in the early 20th century. His private residence in Coconut Grove, Florida, is the present-day location of NTBG’s Kampong Garden. With heritage collections of numerous Southeast Asian, Central, and South American fruits, palms, and flowering trees, The Kampong protects Fairchild’s horticultural legacy and many of his original introductions to the US. It also provides a window into the past that inspires today’s plant hunters and food protectors working toward a more resilient future for our plants and planet.

“The greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add a useful plant to its culture.”

Thomas Jefferson

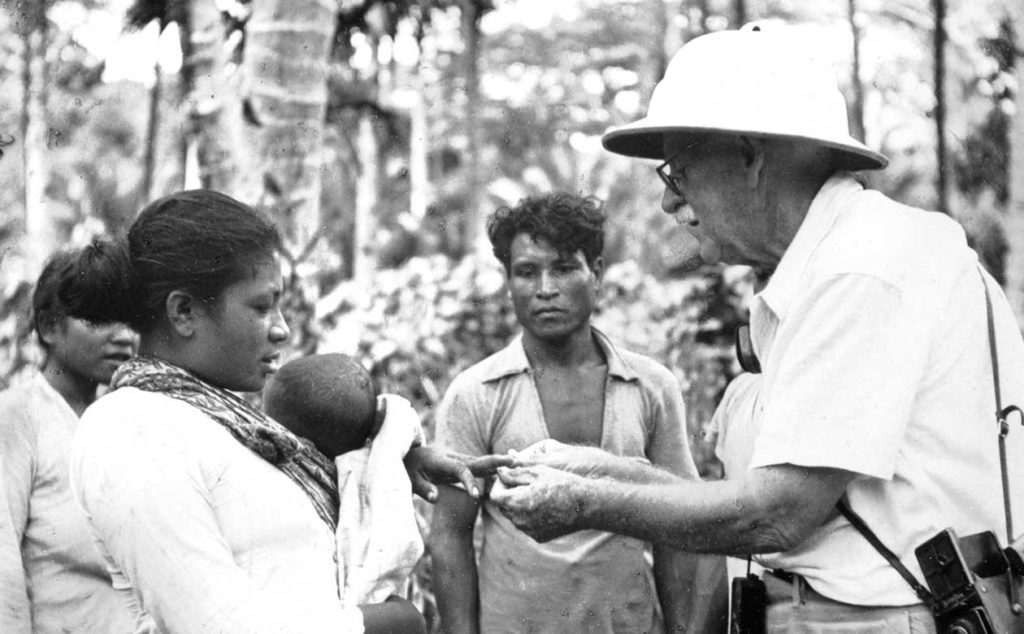

Fairchild, David Fairchild – International Plant Spy and Man of Botanical Intrigue

David Fairchild was born in the late 19th century and grew up in reconstruction-era America. At that time farmers made up most of the country’s workforce and economic opportunity outside of agriculture was sparse. With a fragile post-war economy largely dependent on farming, The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) feared that an invasive species or natural disaster could easily disrupt the nation’s food supply and created a plant pathology division aimed at diversifying the nation’s agricultural offerings.

Fairchild joined the division after receiving his education in horticulture and botany from Kansas College, and traveled the world as part government food spy, part horticulturalist, part adventurer seeking new food and crops for the expanding American economy and diet. After several years of botanical escapades across Europe, Southeast Asia, Central and South America, he became the chief plant collector for the USDA and led the Department of Seed and Plant Introductions vastly increasing the biodiversity of the nation’s food crops.

Fairchild’s Legacy Today

Chances are, at least one of the beverages or meals you consumed today would not have been possible without Fairchild’s introductions. Avocado, mango, kale, quinoa, dates, hops, pistachios, nectarines, pomegranates, myriad citrus, Egyptian cotton, soybeans, and bamboo are just a few of the thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of plants Fairchild introduced to the United States.

“Fairchild was key to the development of agricultural research and introduction stations around the US and in Puerto Rico. Many of those stations are still current and viable, acting as gene banks for plants he brought into the country,” said Craig Morell, Director of The Kampong. “The Kampong houses some of his early introductions, but these were mostly plants he liked to have in his personal garden. We maintain them today in the same fashion that museums curate and preserve antiquities,” Morell continued.

“Fairchild was key to the development of agricultural research and introduction stations around the US and in Puerto Rico.”

Craig Morell, Director of The Kampong

Fairchild’s work fundamentally changed the American diet and agricultural economy, and his career as a plant hunter, gene banker, and horticulturalist continues to inspire those following in his footsteps today.

Modern-Day Plant Hunters Protect Biodiversity Hotspots

Hawaii was selected for NTBG’s headquarters because of its status as a biodiversity hotspot. This means that while rich in biodiversity, Hawaii’s flora and fauna are deeply threatened by climate change, invasive species, and human activity. While the rate of species loss continues to accelerate worldwide, 2020 was a banner year for NTBG’s modern-day plant hunters. Our team of scientists discovered previously unknown populations of nine rare and endangered species including, Hibiscadelphus distans; Melicope stonei; Schiedea viscosa; Lysimachia scopulensis; Lepidium orbiculare; and Isodendrion laurifolium. Bolstering biodiversity hotspots not only strengthens our food supply, it also builds resilience and ensures ecosystems continue to sustain life, supply oxygen, clean air and water.

“These discoveries offer new hope for conservation of Hawaii’s endangered rare plants and native forests,” said Nina Rønsted, NTBG Director of Science and Conservation. “These findings also illustrate the importance of investing in science as a vital tool to better understand and protect the natural world,” she continued.

Like Fairchild, today’s plant hunters are no strangers to thrill and adventure. NTBG botanists have long been known for repelling down sheer cliffs and into steep valleys searching for rare plant life. Today, with the help of drone and mapping technology, NTBG remains at the forefront of tropical plant discovery and conservation.

“Hawaii has been referred to as the extinction capital of the United States,” said Ben Nyberg, NTBG GIS specialist and drone pilot. “It’s home to 45% of the country’s endangered plant population, and we don’t know how climate change and new threats like Rapid Ohia Death will affect these rare plants’ habitats. We are trying to document and collect material as quickly as possible,” he finished.

“These discoveries offer new hope for conservation of Hawaii’s endangered rare plants and native forests.”

Nina Rønsted, NTBG Director of Science and Conservation

Keeping Watch

NTBG sets itself apart in the race to save rare and endangered tropical plants. In addition to collecting, categorizing, and seed banking rare plant material, NTBG outplants thousands of rare and endemic species into our gardens and preserves located across the Hawaiian Islands.

From now through 2022, NTBG will engage in a conservation project called, Securing the Survival of the Endangered Endemic Trees of Kauai supported by Fondation Franklinia. This project will focus on eleven species that either previously grew in the Limahuli Valley or have a remnant population of fewer than ten individuals. Throughout the three-year project, NTBG will collect and propagate seeds and use previous collections from our seed bank to balance the need for substantial seed collection. When the new treelets are strong enough, most will be outplanted in the Limahuli Preserve to monitor and protect them. Alongside the Fondation Franklinia project and with the help of our supporters and collaborators, NTBG remains dedicated to saving as many endangered plant species as possible as we work to protect and restore native ecosystems on Kaua‘i and beyond.

From the outlandish adventures and introductions of a 20th-century plant hunter to modern-day scientists using drones to seek out rare plant life on the steep cliffs and rocky ridges of Kauai, NTBG is learning from the past and leading the way in the fight to protect the future of food, plants, animals, and ecosystems. Learn more and support plant-saving science today.

Healthy Plants. Healthy Planet.

NTBG is a nonprofit organization dedicated to saving and studying tropical plants. With five gardens, preserves and research centers based in biodiversity hotspots in Hawaii and Florida, NTBG cares for and protects the largest assemblage of Hawaiian plants. Join the fight to save endangered plant species and preserve plant diversity today by supporting the Healthy Plants, Healthy Planet campaign.

For NTBG scientists in Hawaii, 2020 was a year of finding unknown plant populations

December 15, 2020 (Kalaheo, Hawaii) — Even as the loss of biodiversity and natural habitats accelerates and is worsened by climate change, scientists at the National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG) on Kauai have located previously unknown populations of at least nine species of rare and endangered native Hawaiian plants. NTBG’s Science and Conservation Director, Dr. Nina Rønsted, described the findings as, “a huge step forward in rare plant conservation. For us, this is the best news of the year.” With your help, NTBG is stemming the tide of plant loss. When you donate to the National Tropical Botanical Garden, you’re a part of this critical work that keeps our plants and our planet healthy.

In 2020, NTBG discovered and mapped 11 individual Gouania meyenii plants, a nearly extinct member of the Buckthorn family, reduced to a few plants on Oahu and thought to be gone from Kauai until this new discovery. NTBG and its collaborators at the Department of Land and Natural Resources, Department of Fish and Wildlife and the state of Hawaii’s Plant Extinction Prevention Program, also located two previously unknown Critically Endangered Flueggea neowawraea trees in Kauai’s Waimea Canyon using a spotting scope and a drone.

Additional population discoveries include the Endangered Geniostoma lydgatei, known from less than 200 plants limited to remote sections of Kauai’s wet forests.

Over the course of the year, even as the coronavirus pandemic disrupted human activity on an unprecedented scale, NTBG played a central role in locating populations of other rare plants including: Hibiscadelphus distans; Melicope stonei; Schiedea viscosa; Lysimachia scopulensis; Lepidium orbiculare; and Isodendrion laurifolium — nine species in total.

Rønsted called the population discoveries, “A new hope for conservation of Hawaii’s endangered rare plants and native forests.” She said the findings illustrate the importance of investing in science as a vital tool to better understand and protect the natural world.

“A new hope for conservation of Hawaii’s endangered rare plants and native forests.”

NTBG Science and Conservation Director, Nina Rønsted

This year’s newly discovered populations have been found in isolated, often difficult to reach areas including steep valleys and sheer cliff faces. NTBG is known for its use of roping and rappelling to reach inaccessible rare plants dating back to the 1970s. Since 2017, NTBG has increasingly used drones and other new mapping technology to locate rare and endangered plants so they can be protected and if accessible, seeds can be collected for restoration work.

In 2020, NTBG scientists have been able to continue their work after implementing safety protocols and distancing measures to ensure the safety of staff and partners.

Working independently and in collaboration with state and federal agencies and organizations such as Hawaii’s Department of Land and Natural Resources’ Division of Forestry and Wildlife, the Plant Extinction Prevention Program, and The Nature Conservancy – Hawaii, and others, NTBG has made significant contributions to plant conservation in Hawaii and the greater Pacific region since it was established by a Congressional Charter in 1964.

Learn more about the work of the National Tropical Botanical Garden at www.ntbg.org.

For media inquiries, contact: media@ntbg.org

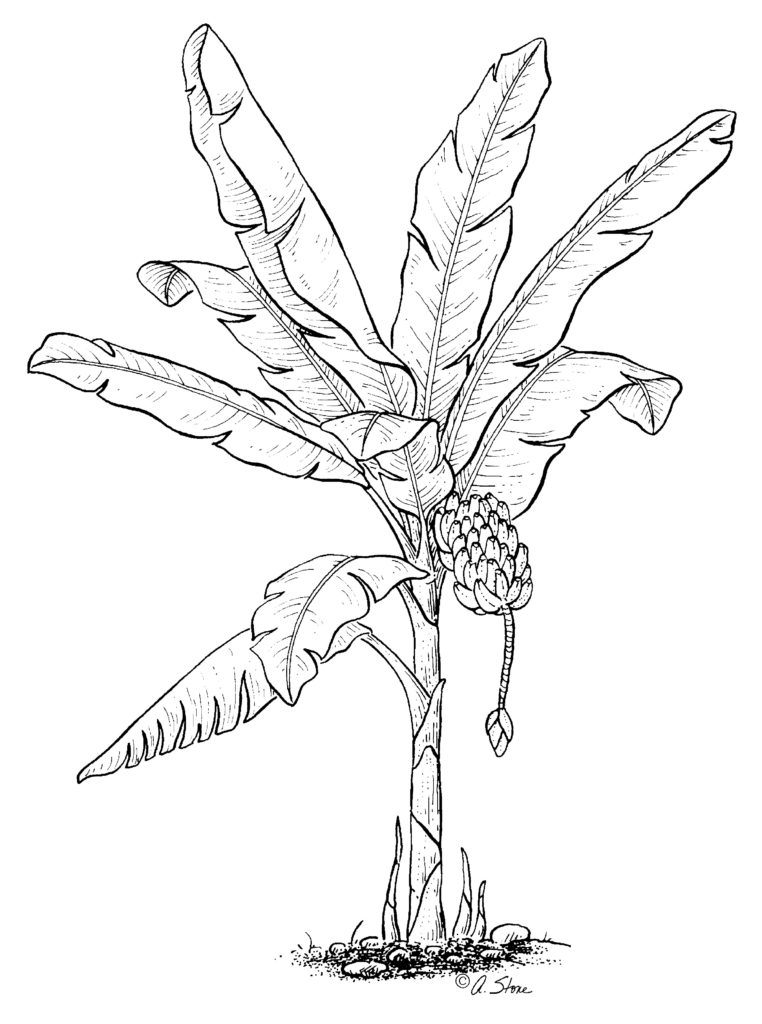

Simple Banana Recipes

We are sharing a few simple banana recipes you can make and share this holiday season. These dishes were adapted from Hawaiian Cookbook by Roana and Gene Schindler. Buy ingredients from your local farms and farmer’s markets when possible to make these dishes even better!

Share your completed dishes with us on social media! Be sure to tag @ntbg on Instagram.

Banana (Maia) Pudding Recipe

Ingredients

- 2 cups coconut milk (or cow’s milk)

- 2 tablespoons sugar

- 1/4 cup raisins (optional)

- 1 tablespoon chopped macadamia nuts

- 3 medium-size ripe bananas, mashed

Cooking Instructions

- Step 1: Scald milk in the top of a double boiler or thick-bottomed saucepan.

- Step 2: Once the milk is scalding, add sugar, raisins, nuts, and bananas. Cook for 10 minutes, stirring constantly until mixture thickens. Remove from heat.

- Step 3: Divide into individual serving dishes, distributing fruit evenly. Cool and refrigerate. Serve with a dollop of red jam, jelly, or whipped cream. We topped with Papaya Vanilla Jam from Monkeypod Jam, a small preservery and bakery located on Kauai.

Drunken Bananas (Maia Ona) Recipe

Ingredients

- 6 small, firm bananas

- 1/2 cup rum mixed with 2 teaspoons lemon juice. We used Kōloa Kauaʻi Spice Rum

- 1 egg, beaten

- 3/4 cup flaked coconut or chopped nuts (almonds, macadamia, walnuts)

- Neutral oil for frying like vegetable oil

Cooking Instructions

- Step 1: Soak whole bananas in rum and lemon juice for about 1 hour. Turn frequently.

- Step 2: Dip bananas in egg and roll in coconut or chopped nuts.

- Step 3: Heat 1/2 inch of oil in a skillet on low and fry bananas slowly until brown on all sides and tender. Drain on paper toweling and serve hot.

Share your completed dishes with us on social media! Be sure to tag @ntbg on Instagram and use the hashtag #ntbgrecipechallenge for a chance to win a prize.

Banana History

Banana or maiʻa in Hawaiian are canoe plants introduced and planted in some of the most idyllic and enchanting places throughout the islands. One ancient story described a banana patch so large you could get lost trying to find your way around it growing deep in Maui’s Waihoi Valley. The story caught the attention of naturalist Dr. Angela Kay Kepler in 2004, and a botanical adventure ensued. Determined to find the legendary banana field, Dr. Kepler hired a helicopter to survey the valley. Sure enough, growing along the Waiohonu River banks, was the largest wild-growing traditional Hawaiian Banana Patch.

After making this discovery, Dr. Kepler phoned Kamaui Aiona, former director of NTBG’s Kahanu Garden and Preserve, managing a small collection of banana varieties. The two returned to the wild patch, collected a pair of young specimens, and returned them to the garden collection where they are still growing. Today, Kahanu’s maia collection exceeds 30 varieties and is one of the most diverse in the State of Hawaii. This collection is essential to the safeguarding the world’s most popular tropical fruit.

Strength in Numbers

A rare collection of bananas at Kahanu Garden safeguards species diversity and the world’s favorite tropical fruit

The world’s most popular tropical fruit is one of the most susceptible to disease. NTBG’s Kahanu Garden maintains a collection of rare bananas that is a safeguard preserving plant diversity of this important tropical food crop and your breakfast. With your help, NTBG is stemming the tide of plant loss and food insecurity. When you donate to the National Tropical Botanical Garden, you’re a part of this critical work that keeps our plants and our planet healthy.

It is a story that is all too common in 2020. A mysterious disease quietly spreads far and wide before its life-threatening symptoms appear. By the time the disease is identified, it’s impossible to stop and takes a heavy toll. While familiar, this story is not about the present COVID-19 pandemic but rather a fungus wreaking havoc on banana crops worldwide and threatening the existence of the most widely consumed Cavendish variety.

If you ate a banana today, chances are you were able to easily acquire it from a local supermarket or cafe. It probably looks and tastes just like every other banana you have ever purchased, and you could find one just like it from nearly any grocer or roadside fruit stand on the planet. This is because monoculture crops of Cavendish bananas account for 47% of global banana production and 99% of bananas cultivated for commercial export.

Monoculture is a form of agriculture focused on growing one type of crop at a time. In the case of Cavendish bananas, not only are they the primary variety cultivated for commercial consumption and trade, the crops are genetically identical. This means that every Cavendish banana you have eaten is a clone of one that came before it. While monoculture does offer the benefit of efficiency and scale, it also increases the risk of disease and crop vulnerability. In other words, if a disease affects one plant, it can affect them all. Banana farmers and barons of the early 20th century are no stranger to the vulnerabilities of banana monoculture. Until the mid 20th century, the Gros Michel variety of banana was the most popular, commercially available variety. Still, fungus all but wiped it out in the 1950s, replaced by today’s heartier, or so thought, Cavendish variety.

A race with no end in sight

Tropical Race 4 (TR4), also known as Fusarium Wilt or Panama Disease, is a soil-borne fungus that enters banana plants from the root, blocks water flow throughout the plant, and causes it to wilt. At present, TR4 cannot be controlled with fungicide or fumigation and has been found in banana-growing regions across Asia, Africa, Australia and was discovered in South America, where most commercial bananas are produced in 2019.

Bananas are the world’s most popular tropical fruit. In fact, the average American consumes more than 26 pounds of banana every year. While not exactly a staple of the American diet, bananas are one of the most economically important food crops worldwide and responsible for an annual trade industry of more than $4 billion, only 15% of which is exported to the United States, Europe, and Japan. What is particularly devastating about the fungus’ potential to overrun our most popular variety is that most bananas are consumed by people in developing countries where affordable food sources and nutrient-rich calories can be hard to come by. With a great demand for bananas and monoculture crops highly susceptible to TR4 and other fungi, scientists are racing the clock to develop new disease-resistant bananas, but looking to history is likely where the answer lies.

Bananas with a legendary past and promising future

Long before westerners arrived in Hawaii, ancient Polynesians voyaged to the islands in double-hulled sailing canoes. To sustain life throughout their journey, and once they reached their destination, they brought a selection of at least two dozen species of plants for food, clothing, structure, medicinal and cultural purposes. These plants are commonly referred to as “canoe plants,” and even though they were introduced to the island, they are an essential part of Hawaii’s cultural history.

Banana or maiʻa in Hawaiian are canoe plants introduced and planted in some of the most idyllic and enchanting places throughout the islands. One ancient story described a banana patch so large you could get lost trying to find your way around it growing deep in Maui’s Waihoi Valley. The story caught the attention of naturalist Dr. Angela Kay Kepler in 2004, and a botanical adventure ensued. Determined to find the legendary banana field, Dr. Kepler hired a helicopter to survey the valley. Sure enough, growing along the Waiohonu River banks, was the largest wild-growing traditional Hawaiian Banana Patch.

“The number of early varieties is a fraction of what it once was, and research to verify each is ongoing. Kahanu Garden serves as a haven where they can be preserved and shared for future generations.”

Mike Opgenorth, Kahanu Garden Director

After making this discovery, Dr. Kepler phoned Kamaui Aiona, former director of NTBG’s Kahanu Garden and Preserve, managing a small collection of banana varieties. The two returned to the wild patch, collected a pair of young specimens, and returned them to the garden collection where they are still growing. Today, Kahanu’s maia collection exceeds 30 varieties and is one of the most diverse in the State of Hawaii.

“In recognition of the threat of losing indigenous crop diversity, NTBG recently adopted a strategic goal to collect and curate all extant cultivars of Hawaiian canoe plants,” said Mike Opgenorth, current Director at Kahanu Garden. “The number of early varieties is a fraction of what it once was, and research to verify each is ongoing. Kahanu Garden serves as a haven where they can be preserved and shared for future generations.” he continued.

Feeding the world starts at home

Today, Kahanu Garden is carrying on the critical work of protecting banana diversity and Hawaii’s botanical heritage and re-introducing these important varieties to local food systems. “Existing commercial varieties do not exhibit the resiliency to combat these new diseases,” said Opgenorth. “It is so important that other banana varieties remain available so that we can defend irreplaceable genetic diversity that will help feed the world,” he finished.

Feeding the world starts at home for NTBG and Kahanu Garden. Together with partners at Mahele Farm, the organizations are working together to provide for the isolated Hana Maui community and share the traditional plant knowledge of Hawaii’s kupuna (elders).

“Over the past ten years, weʻve launched ourselves into the Hawaiian-style study of maia,” said Mikala Minn, Volunteer Coordinator at Mahele Farm. “As small farmers dedicated to feeding our community, the crop variety was a perfect fit for our weekly food distributions. As we shared the fruit and learned the best ways to prepare each type, stories from our kupuna came to light. This personʻs papa would put them in the imu, half-ripe. Another kupuna grew up eating them boiled and mashed. Others made poʻe, a kind of maiʻa poi.,” he continued. Mahele Farm distributes approximately 50 pounds of fresh produce to kupuna at the Hana Farmers market every week and helps maintain a small collection of Hawaiian bananas at the Hana Elementary school.

“This personʻs papa would put them in the imu, half-ripe. Another Kupuna grew up eating them boiled and mashed. Others made poʻe, a kind of maiʻa poi.”

Mikala Minn, Volunteer Coordinator at Mahele Farm

Today’s agricultural and botanical problems are complex, but looking to the past, protecting plant diversity, and encouraging local farmers, schools, and even home gardeners to diversify is an excellent and effective step in the right direction.

Healthy Plants. Healthy Planet.

NTBG is a nonprofit organization dedicated to saving and studying tropical plants. With five gardens, preserves and research centers based in Hawaii and Florida, NTBG cares for and protects the largest assemblage of Hawaiian plants. Join the fight to save endangered plant species and preserve plant diversity today by supporting the Healthy plants, healthy planet campaign.

Tropical Crops Key in the Fight for Food Security

Thanks to a chance encounter in graduate school, Diane Ragone, Ph.D., director of the Breadfruit Institute at NTBG, dedicated her life to documenting and preserving a nutritious, starchy, and storied fruit of the Pacific. Breadfruit, or ulu as it is known in Hawaii, may be the key to preventing the loss of traditional and culturally significant food crops and stabilizing food and economic security in the tropics. NTBG and the Breadfruit Institute are stemming the tide of plant loss and food insecurity with your help. When you donate to the National Tropical Botanical Garden, you’re a part of this critical work that is keeping our plants and our planet healthy.

A Chance Encounter

In 1981, Diane Ragone, a horticulturist interested in tropical fruit, moved to the Hawaiian Island of Oahu for graduate studies at the University of Hawaii in the Horticulture Department. After a chance encounter and single taste of the nutritious, starchy, and storied fruit, commonly known as breadfruit or ulu in Hawaii, Diane decided to make it the subject of a term paper. “The history of breadfruit was so interesting to me because of how widely it was grown throughout the Pacific Islands and how important it was culturally and as a food staple for so many Pacific Islanders for centuries,” she said.

“The history of breadfruit was so interesting to me because of how widely it was grown throughout the Pacific Islands and how important it was culturally and as a food staple for so many Pacific Islanders for centuries.”

Dr. Diane Ragone, Director, the Breadfruit Institute

History and Botanical Interests

Breadfruit originated in New Guinea and the Indo-Malay region and was spread throughout the vast Pacific by voyaging islanders. Europeans discovered breadfruit in the late 1500s and were delighted by a tree that produced prolific, starchy fruits that resembled freshly baked bread in texture and aroma when roasted in a fire.

Sir Joseph Banks, who sailed on HMS Endeavour with Captain Cook to Tahiti in 1769, recognized the potential of breadfruit as a food crop for other tropical areas. He proposed to King George III that a special expedition be commissioned to transport breadfruit plants from Tahiti to the Caribbean. This set the stage for one of the grandest sailing adventures of all time – The ill-fated voyage of HMS Bounty under the command of Captain William Bligh.

What is little known is that Captain Bligh returned to Tahiti on the aptly named HMS Providence to continue the breadfruit voyage. Several Tahitian varieties, and an unknown variety from Timor, were successfully introduced to the Caribbean in 1793. While many accounts dismiss this epic plant introduction as a failure because the islands’ population did not initially accept this new crop as a food, subsequent centuries have proved the value of breadfruit to the Caribbean and other tropical areas.

A renewed interest in breadfruit emerged in the 1920s and 1940s after World War II when botanists and scientists realized that many traditional food crops and cultivation practices were at risk of disappearing from the Pacific Islands. “Plant introductions were of particular interest to me, so I approached my research from the angle of collection, conservation, and documentation of breadfruit diversity,” said Dr. Ragone. “It was fascinating for me to learn that there were places in the Pacific that had documented 50, 60, even a hundred varieties of breadfruit,” she continued.

In 2003 Diane established the Breadfruit Institute to promote the conservation, study, and use of breadfruit for food and reforestation and is a global leader in efforts to conserve and use breadfruit diversity to support regenerative agriculture, food security, and economic development in the tropics.

Food Security and Economic Opportunity

Compared to an annual field crop, breadfruit trees are easy to plant and can produce anywhere from 300 to 1,200 pounds of starchy, nutritious food every year for decades. Breadfruit grows in tropical regions worldwide, which have some of the highest instances of food insecurity and poverty anywhere. 85% of the places around the world where hunger and poverty are most acute, breadfruit can grow. This makes breadfruit an incredible resource for bolstering food security and creating economic opportunity for the farmers and families where it is needed most.

“Even in Hawaii, it’s hard to be a farmer and make enough money to pay your bills.”

Noel Dickinson, NTBG Research Technician

“Even in Hawaii, it’s hard to be a farmer and make enough money to pay your bills,” said Noel Dickinson, Research Technician at National Tropical Botanical Garden. “What we are trying to demonstrate with the Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforest in McBryde Garden is a way for farmers and individuals in Hawaii and tropical regions around the world to diversify and utilize all of their land with ulu as the backbone of their system,” she continued.

Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforestry (ROBA)

Agroforestry is a farming method that integrates trees, shrubs, and other plants with crops or animals in ways that provide economic, environmental, and social benefits. In 2017, NTBG’s Breadfruit Institute established a two-acre Regenerative Organic Breadfruit Agroforestry demonstration in McBryde Garden with funding from the Hawaii Department of Agriculture and Patagonia Provisions. The demonstration garden contains more than 100 plant species and varieties, which are monitored weekly for production. In 2020, the ROBA demonstration has produced more than 6,000 pounds of fresh food, approximately 20,000 meals, which has been donated to staff, volunteers, and organizations mitigating food insecurity on Kauai during the pandemic.

“One pound of breadfruit feeds 2-4 people,” said Kelvin Moniz, Executive Director of the Kauai Independent Food Bank. “We calculate it by assuming people are putting 2-4 oz. of starch on their plate during a meal. With the breadfruit from NTBG and some other local sources, we handed out one ulu per car and were able to give away more than 200 during one Friday afternoon distribution,” he concluded.

“At first, people were really surprised that we had ulu at the Food Bank, and gradually they have started to ask for it more and more. It is great to see the desire for ulu increase and all of the different ways people are preparing and sharing it with their families.”

Kelvin Moniz, Kauai Independent Food Bank

Nutritionally breadfruit compares favorably with other starchy staple crops commonly eaten in the tropics, such as taro, plantain, cassava, sweet potato, and rice. It is a good source of dietary fiber, iron, potassium, calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium with small amounts of thiamin, riboflavin, and niacin. Breadfruit is gluten-free and a complete protein, providing all of the essential amino acids necessary to human health. “At first, people were really surprised that we had ulu at the Food Bank, and gradually they have started to ask for it more and more,” said Kevin. “It is great to see the desire for ulu increase and all different ways people are preparing and sharing it with their families,” he finished.

Learning from the Past to Farm for the Future

Breadfruit has long been a staple crop and a critical component of traditional agroforestry systems throughout Oceania. There is so much we can learn and apply today from how it has been cultivated throughout history. “Breadfruit agroforestry typifies regenerative agriculture as indigenous people of the tropics have practiced it for centuries,” said Dr. Ragone. “They had no outside inputs, only organic resources provided by the land and sea, so every part of the agroforestry system interacted and worked together to rebuild and add nutrients back into the soil,” she continued. Unlike other starchy food crops, breadfruit does not require annual soil tilling and provides more significant carbon sequestration benefits for the environment, which helps mitigate climate change.

“What is most dear to my heart is local abundance. We need to diversify agriculture in tropical regions, and breadfruit is an important staple crop that can do that while providing local and community self-sufficiency and food security.”

Dr. Diane Ragone, Director, the Breadfruit Institute

Over the last decade, more than 100,000 breadfruit trees have been planted in Hawaii and around the globe thanks to the efforts of The Breadfruit Institute and partners in its Global Hunger Initiative such as the Hawaii Homegrown Food Network, Trees That Feed Foundation, Cultivaris, and many more. Now that individuals, families, and farms have more access to breadfruit, so do entrepreneurs who can develop novel food and products, leading to economic growth. “What is most dear to my heart is local abundance,” said Dr. Ragone. “We need to diversify agriculture in tropical regions, and breadfruit is an important staple crop that can do that while providing local and community self-sufficiency and food security.”

Healthy Plants. Healthy Planet.

From its origins in Oceania to historical expeditions, botanical introductions, and conservation efforts, breadfruit has been on an incredible journey to the modern world. Thanks to generous supporters, partners, and volunteers like you, NTBG and the Breadfruit Institute will continue to study, fuel economic growth, and drive agricultural innovation with breadfruit.

Want to get involved? Donate to the Healthy Plants. Healthy Planet campaign to support NTBG science, research, and conservation efforts today and learn more about opportunities to visit and volunteer. “My husband and I are avid gardeners and learned about the wonders of breadfruit during a visit to McBryde Garden in 2015,” said Anne Cyr, NTBG volunteer. “A later trip to St. Kitts and the West Indies broadened our understanding of breadfruit’s importance, and we signed up to volunteer at the Breadfruit Institute during our next visit to Kauai. We planted taro, harvested, and weighed lots of breadfruit and learned so much! We can’t wait to get back and work beneath the beautiful and bountiful trees again,” she exclaimed.

Give now to support food security and check out these resources, entrepreneurs, and partners for more information on breadfruit.

Additional Resources

An Interview with the Mother of the Breadfruit Movement, Hawaii Public Radio

Breadfruit Institute

Breadfruit Agroforestry Guide

Patagonia Provisions Agroforestry Partners

Global Hunger Initiative

Hawaii Homegrown Food Network

Maui Breadfruit Company

.svg)