Category: The Kampong

Growing the Next Generation of Botanists at the ICTB at The Kampong

Tropical Botany student Jenny Morris taking field notes in Costa Rica. Photo by Danielle Ward.

By Jon Letman, Bulletin Editor

Among the many shortages the world faces today, one often overlooked is a lack of botanists. At a time of unprecedented crises, including a dramatic loss of biodiversity, highly trained botanists are in short supply. “Today, we need plant scientists more than ever,” says Dr. Chris Baraloto, director of the International Center for Tropical Botany (ICTB) at The Kampong in Miami, Florida.

For more than a decade, scientists have expressed concern about declining support for plant science education. As academic and funding priorities have shifted, universities have merged fields, deemphasizing botany programs. Reduced training and recruitment, along with retirement, has exacerbated the shortage. Dr. Brian Sidoti, director of The Kampong says, “A fresh influx of trained plant scientists is essential to carry forward research, innovation, and expertise. Their contributions will be pivotal in devising solutions to the global challenges we face.”

Plants not only provide oxygen, food, fiber, fuel, and medicine, they also offer habitat and safe refuge for wildlife and inspiration and recreation for humans. Plants fulfill essential ecosystem services like carbon and nutrient cycling, mitigate the impacts of climate change and storms, and perform other critical functions. But as threats to plants synergize, more plant scientists are urgently needed.

Happy botany students outside the ICTB at The Kampong. Photo by Gaby Orihuela.

That’s where the ICTB at The Kampong comes in. Chris says the new facility is uniquely equipped to train the next generation of botanists. The ICTB at The Kampong is a collaboration between the National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG) and Florida International University. The new facility builds upon a decades-long history of tropical plant collection and research at the home and garden of botanist David Fairchild, who purchased and named The Kampong in 1916.

As Fairchild introduced thousands of ornamental and food plants from around the world, his home and garden became a magnet for fellow scientists and plant enthusiasts. Among them was Harvard botany professor Richard A. Howard who frequently visited The Kampong beginning in the 1940s. Professor Howard first invited graduate students interested in tropical plant science to Miami and later, with Harvard botanist P. Barry Tomlinson, started an immersive course in taxonomy, anatomy, and morphology.

Catherine “Kay” Sweeney, who took ownership of The Kampong after Fairchild and later gifted it to NTBG, supported the Tropical Botany course as an ideal use of the property’s living collections consistent with Fairchild’s legacy.

The course continued under Walter Judd, a professor and curator of the herbarium at the University of Florida. A former student of Richard Howard, Judd expanded the course to four weeks. Over three decades the course trained more than 250 students who have become leaders in tropical plant sciences. When Chris Baraloto arrived in 2015, he was determined to build on that legacy.

The next chapter in tropical botany

Standing outside the ICTB’s orange and white Miami limestone (oolite) façade, Chris surveys the newly planted landscaping, an assemblage of more than 170 species mostly native to Florida and the West Indies and typical of hardwood hammock dry habitat. Although native, many of the plants are rarely seen, giving the landscaping horticultural, botanical, and aesthetic value that complements the exotic living collections at The Kampong.

Built on a two-acre parcel, the ICTB is connected to The Kampong by physical space and a vision for the future. At the center of that vision are students like those who participated in the Tropical Botany course in May and June of this year. The 16 students, coming from ten countries[1], represented a range of experiences and backgrounds.

Housed in The Kampong’s dormitory, a short stroll from the ICTB, the botanists began their days with morning lectures followed by collecting plant material at The Kampong and nearby gardens, including Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden and the Montgomery Botanical Center. Afternoons were spent in the ICTB labs studying morphology and anatomy and learning how to identify more than 1,400 species from 850 genera and 200 families. Field trips took them to the Florida Keys, Everglades National Park, and other sites.

Left: Boris Llamas, a student from Guatemala, holding Fuchsia paniculata. Photo by Danielle Ward. Right: Chris Baraloto, Director of the ICTB at The Kampong inspects plant ID samples. Photo by Jon Letman

With ample space for instruction, research, lab work, and a herbarium with capacity for 120,000 specimens, Chris says the LEED-certified two-story ICTB is equipped to host a broad range of lectures, workshops, symposia, in-person and virtual classes, and meetings. The facility can accommodate graduate students and research assistants in office and multi-function spaces that allow for both collaboration and autonomy. Over time, Chris hopes the ICTB at The Kampong will become known as the preeminent research and teaching hub for scientists focused on neotropical flora.

Botany professor Dr. Lucas Majure (who took over Walter Judd’s position at UF) has joined Chris to share teaching responsibilities for the Tropical Botany course. Brian Sidoti also gave a presentation on his subject of expertise, the Bromeliaceae. Brian says the collaboration between ICTB and The Kampong creates a space where graduate and undergraduate students can excel, while maximizing use of The Kampong’s housing facilities and living collections as an outdoor laboratory.

One of the participants in this year’s Tropical Botany course was Jenny Morris, a science officer for the Bahamas National Trust. Jenny stressed the value of living and learning with fellow botanists and having time to discuss botany and science as well as culture, customs, academics, and environmental law from an international perspective. The experience, she says, is critical to becoming an effective teacher or mentor. “I feel like you cannot be an educator if you don’t explore first.”

Landscaping outside of the ICTB at The Kampong includes species native to a Florida hardwood hammock dry habitat. Photo by Jon Letman.

Studying alongside Jenny was NTBG plant records manager Kevin Houck who says the course improved his understanding of phylogenetics and taxonomy, fields which will bolster his data management and GIS mapping for the Garden. Taking the course, he believes, also enables him to more effectively coordinate with NTBG’s herbarium while strengthening curation and the assessment of collection priorities.

Into the field

Following four weeks of instruction at the ICTB at The Kampong, having built rapport and developed practical skills, the students embarked on a two-week trip to the lowland tropical moist forests of Costa Rica. Working with FUNDECOR, a local NGO, the students learned how to conduct a biodiversity inventory, assess the value of intact forest, and identify land suitable for a biodiversity corridor connecting conservation lands.

New skills gained included setting camera traps, inventorying insects and mammals, and making use of recently acquired plant identification techniques in the wild. Over eleven long days of field work, the students made several hundred herbarium vouchers comprising more than 300 species of 142 genera collected in an area not previously inventoried. This portion of the course, Chris explains, was both physically and mentally demanding, with long hours under difficult conditions, and high expectations.

“There was little ‘eco-tourism’-like about it,” he says. “We were there to collect meaningful data. The world is changing too rapidly for us to squander our time.”

Learning how measuring and identifying trees can help quantify carbon storage and sequestration potential, students met with landowners to discuss perspectives on protecting private land. Their work also demonstrated the high conservation value of a wildlife inventory in fragmented, but diversity-rich target areas. The training gave students a chance to consider Costa Rica’s ecosystem service payment model and, Chris says, “will definitely have an impact.”

Examining a strawberry poison dart frog (Oophaga pumilio). Left photo by Jenny Morris, right photo by Danielle Ward.

Danielle Ward, a PhD student at the University of California Berkeley, calls the course “intense” but “very positive” and “solutions focused.” She says it required great physical and mental stamina, but added that the ICTB at The Kampong faculty, staff, and facilities provided everything necessary to succeed. She says the highly integrated, unified program and welcoming, supportive staff will contribute to future collaborations between the network of botanists.

Another PhD student, Vanina Gabriela Salgado from Argentina, specializes in studying the large plant family Asteraceae. Coming from a temperate climate, she says the course opened her eyes to the dynamic ways in which diversity changes as it moves south. Vanina emphasized the value of the course for teaching students how to collect plant material in challenging conditions, how to orient oneself in the wild, and how to walk safely in unfamiliar surroundings. These are skills one cannot learn from a book, Vanina says. “There’s nothing like having someone mentor you on that.”

“I know this course is going to have a big impact on my career in the long term,” she adds. “Both personally and professionally it already has.”

Looking ahead, Chris emphasizes the value of this new, more international model for the Tropical Botany course. For the students, some of whom are already working for NGOs, government agencies, or as professors in their home country, the opportunity to undergo intensive training and develop relationships is priceless. Chris sees the Tropical Botany course, and the work being done at ICTB at The Kampong, as the continuation of a storied legacy of plant science education and research.

“There are very few courses like this,” Chris says. “We are unique in providing scholarship funds to those who might not receive such training. At this consequential time for the planet, he believes, opening doors and creating new opportunities couldn’t be more important. “These are the people we need to be training first,” says Chris. “They are the ones working at the forefront of the biodiversity crisis and they will have the most immediate impact.”

For more information about the Tropical Botany course, contact Dr. Chris Baraloto at cbaralot@fiu.edu.

[1] Argentina, Guatemala, Peru, Bahamas, Dominican Republic, Haiti, Nigeria, Tanzania, Spain, and United States

People need plants. Plants need you.

Plants nourish our ecosystems and communities in countless ways. When we care for plants, they continue caring for us. Help us grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants.

Biocultural Conservation at NTBG

Weaving hala leaves for a pāpale (hat). Photo by Shandelle Nakanelua

Defining our approach to restoring relationships between plants, people, and places.

At its heart, biocultural conservation recognizes the inseparable bonds between humanity and nature. Many Indigenous cultures share concepts of kinship across species, elements, and places. In Hawaiʻi, the idea of ʻohana (family) transcends humans. For example, kalo (taro) is the older brother of kānaka (Hawaiians). Native Hawaiian scientist Keolu Fox says, “when I say that the land is my ancestor, that is a scientific statement.”

Anishinaabe writer Patty Krawec shares the phrase “nii’kinaaganaa,” encapsulating the belief that “the world is alive with beings that are other than human, and we are all related with responsibilities to each other.”

Biocultural conservation accounts for these relationships, honoring the familial bonds that Indigenous communities maintain with biodiversity, integrating the life-sustaining, ecological knowledge cultivated over generations as they care for the land.

Left: Limahuli Garden Visitor Program Manager Lahela Chandler Correa. Right: Hale Hoʻonaʻauao (House-of-teaching) in McBryde Garden. Photos by Erica Taniguchi.

Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American U.S. secretary of interior, said, “Indigenous knowledge must be at the center of our conservation efforts, as we restore a cultural balance to the lands and waters that sustain us.” This call to action is echoed by the United Nations, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, and other partners.

Biocultural conservation integrates communities in collective stewardship and decision-making. It aims to protect not only plants and physical landscapes, but also cultural heritage, languages, practices, and social systems that are connected to the health of our shared environment. In biocultural conservation, our relationship with plants and places deeply matters. Perceiving the reciprocity of this relationship can lead to lasting, transformative change.

At NTBG our mission to perpetuate plants, tropical ecosystems, and cultural heritage is rooted in biocultural conservation. Below are six examples of what this concept means to our staff. Each has their own way of expressing biocultural conservation. As you read, we hope you’ll consider what plants mean to you and, conversely, what you mean to them.

—David Bryant, Director of Communications

Left: Science and Conservation Director Nina Rønsted. Photo by Jon Letman. Right: Hala (Pandanus) at Kahanu Garden. Photo by Seana Walsh.

On the global stage, biocultural conservation can be seen in international agreements such as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, signed by 188 countries in 2023. The framework’s vision is “living in harmony with nature where, by 2050, biodiversity is valued, conserved, restored and wisely used, maintaining ecosystem services, sustaining a healthy planet and delivering benefits essential for all people.”

This vision puts the relationships between people and nature at the center of solutions to ensure the best possible data, knowledge, and practices contribute to effective biocultural conservation.

To cite one example, in Colombia, dry forests are categorized as critically endangered ecosystems due to extensive clearing for cattle ranching and agriculture. To address this, a series of forest plots have been established in collaboration with local communities, that not only measure scientific biodiversity indicators, but also use community input to identify issues related to deforestation, biodiversity use, and valuation of ecosystem services. The hope is to find conservation solutions that satisfy both ecosystem protection and local societal needs.

In Canada and Aotearoa (New Zealand), negotiated settlements of Indigenous rights in fisheries management are creating sustainable marine biocultural conservation models based on Indigenous knowledge and long-term commitments to sustain resources and ecosystems. These offer an alternative to the polarizing all-or-nothing models of commercial fisheries vs. marine reserves.

There are countless other examples around the world that illustrate how, through a combination of local, national, and international legislation and initiatives, biocultural conservation honors the intrinsic relationships between nature and humanity.

Similarly, at NTBG, we are harnessing our experience and expertise to build conservation programs that align with cultural values and community priorities while enriching life through the perpetuation of tropical plants, ecosystems, and cultural heritage.

—Dr. Nina Rønsted, Director of Science and Conservation

Lei Wann, Director of Limahuli Garden and Preserve. Photo by Erica Taniguchi.

I see biocultural conservation as a way of expressing the intrinsic and scientific relationship between people, places, culture, and science. It’s a way of acknowledging that we practice science in its Western form, but there’s so much more to our work than that. At its core, these are deep connections and relationships with plants that have existed for generations.

Often what we find is that the ʻike (knowledge) we have of plants from our ancestors aligns with scientific research and findings. Biocultural conservation is the way we’ve come to express that science has such deep meaning here in Hawaiʻi because of the ʻike from our kupuna (elders) and the deep relationships we share with plants.

—Lei Wann, Director of Limahuli Garden and Preserve

Left: Brian Sidoti, Director of The Kampong. Photo by Alejandra Libertad. Right: Entryway at The Kampong.

NTBG’s only garden outside of Hawaiʻi, The Kampong, is in Miami, Florida. Our name, Kampong, can be translated as “village.” In this spirit, we use this space to honor the Indigenous communities that once lived here while celebrating the significance of our living collections to the rich tapestry of immigrant communities that make up Miami today.

At The Kampong, biocultural conservation is influenced by those who resided here before us. This includes Dr. Eleanor Galt Simmons, one of Dade County’s first licensed female physicians whose office and stable are on the grounds of The Kampong. From the 1890s, Dr. Simmons treated patients, making house calls by horse, buggy, and boat. Today we are planning a guided visitor experience that will interpret medicinal plants used by Dr. Simmons as well as by Native Miccosukee and Seminole peoples.

We also tell the story of plants collected by famed botanist Dr. David Fairchild who introduced thousands of edible and ornamental plants to the United States. David Fairchild named this site The Kampong in 1916.

Another key figure at The Kampong was Catherine “Kay” Hauberg Sweeney, an intrepid and impassioned plant collector who, with her husband, purchased this property in 1963. Mrs. Sweeney devoted her life to ensuring The Kampong remained a refuge for tropical plants and plant enthusiasts. The commitment of these early inhabitants laid the foundation for The Kampong today.

Looking ahead, we continue to add native plants to our collections. In collaboration with faculty of the International Center for Tropical Botany at The Kampong, our pursuit of plant research, public outreach, and education, is rooted in biocultural conservation. We remain focused on three themes: preserving tropical plant diversity; conservation and management of threatened tropical species and habitats; and fostering an understanding of tropical plant-based goods and services such as food, fuel, fiber, and medicine.

—Dr. Brian Sidoti, Director of The Kampong

Uma Nagendra, Limahuli Preserve Conservation Operations Manager. Photo by Erica Taniguchi

Central to biocultural conservation is human culture and our relationship to the natural world. This connection inherently expands our conservation practices, values, and priorities. Biocultural conservation provides us with more sources of knowledge and expands the range of people who are enthusiastic and invested in our work.

Biocultural conservation guides nearly all we do at Limahuli Garden and Preserve. But often overlooked are defining personal experiences. This is what it feels like to me: the shade of young kukui (Aleurites moluccana) saplings serving as nurse trees in newly cleared restoration areas. It feels like the stickiness of hau (Hibiscus tiliaceus) branches being stripped for cordage. I hear it in voices raised in oli (chants) at the beginning of each workday, and in the bird cries of uaʻu (Pterodroma sandwichensis) and aʻo (Puffinus newelli) barking in the Upper Limahuli Preserve.

Biocultural conservation tastes like refreshing ʻōhiʻa ʻai (Syzygium malaccense) fruits plucked from the tree and Tahitian prawns fished from the stream. It is the weight of kōpiko (Psychotria mariniana) branches and ʻalaheʻe (Psydrax odorata) collected for carving. Biocultural conservation maintains the ungulate fence, but also knows the names of the neighborhood hunters to call when you find a sign of pigs in the valley.

Biocultural conservation is not only theory; it is practice. It is action. It is listening, learning, striving, making mistakes, and trying again. Biocultural conservation is a lei formed from the interwoven strands of people, plants, and places which we are communally, perpetually weaving.

—Dr. Uma Nagendra, Conservation Operations Manager, Limahuli Preserve

Left: Mike Opgenorth, Kahanu Garden and Preserve Director. Photo by Shandelle Nakanelua. Right: Kahanu Garden.

At Kahanu Garden and Preserve, biocultural conservation teaches us the critical role humans play in the survival of native ecosystems. On the coast of East Maui, tradewinds deliver sheets of Hāna’s famous ua kea (white rain). Inside Kahanu Preserve’s hala (Pandanus tectorius) forest, the trees provide shelter beneath its canopy. There we can marvel at the tree’s fruit which resembles pineapples arching from the end of branches. The space evokes memories of the people who once used material from these trees to create thatched mats, hats, sails, and lei. Even the tree’s hīnano (male flower) was considered an aphrodisiac. Hala’s stilt-like roots also prevent erosion along the rocky cliffs where they grow.

Coastal hala forests, like those found in the Kahanu Preserve, have been dwindling across Hawaiʻi as a result of invasive species and habitat lost to agriculture and development. An introduced scale insect attacks hala, as is evident by the powdery shells sucking life from its leaves. Highly invasive African tulip trees emerge and spread over the hala canopy where they disperse thousands of seeds.

The future of hala forests like those found at Kahanu Preserve is uncertain, but cultural practitioners seeking fresh plant material have the opportunity to remove invasive plants, perpetuating their own practices while helping save young hala trees and contributing to the long-term health of the forest.

This is the interdependence of biocultural conservation at Kahanu Garden and Preserve. Without hala trees, cultural practices would almost certainly cease to exist. And without human stewards of the forest, the trees would also likely be lost. Through clearing invasive plants and supporting the growth of hala seedlings, we can perpetuate culture, preserve an ecosystem, and provide resources for future generations while protecting the island that protects us.

—Mike Opgenorth, Director of Kahanu Garden and Preserve

Mike DeMotta, Curator of Living Collections. Photo by Erica Taniguchi.

For me, an effective and meaningful biocultural conservation program at NTBG requires a full understanding of Hawaiian values, a Hawaiian world view, and my place in it. Kuleana (responsibility) and aloha ʻāina (love of the land) are values that guide my decision-making process.

The first Hawaiians understood that their actions needed to be sustainable so their relationship with the natural world could enhance biodiversity and ecosystem function. Prior to contact with the west, Hawaiians saw the importance of native ecosystem function as kinolau (physical manifestation) of the kini akua (pantheon of gods). All elements of nature — water, earth, the ocean — were kinolau of major deities.

Living with these sacred elements demanded thoughtful actions and deification required Hawaiians to respect and care for nature in a way that benefited people and ecosystems. This enabled Hawaiians to successfully settle in these islands and support a large population without the negative impacts so common today.

We can be guided by these principles, integrating them into the management of our gardens and preserves in a way that mitigates the harm caused by our modern lifestyle. By embracing biocultural conservation, we can acknowledge what we need to change and identify traditional practices that, if revived, can help maintain ecosystem function. A full understanding of how we fit into nature is essential in rebuilding natural systems that are abundant and resilient.

—Mike DeMotta, Curator of Living Collections

People need plants. Plants need you.

Plants nourish our ecosystems and communities in countless ways. When we care for plants, they continue caring for us. Help us grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants.

New Art Exhibit at The Kampong honors Biscayne Bay’s Heritage and Future

Miami, Florida (September 6, 2023) — Bridge Initiative, a Miami-based environmental arts organization, has joined The Kampong of the National Tropical Botanical Garden to present the groundbreaking exhibition Biscayne. This collaborative endeavor showcases the vital role of contemporary art in advocating for the preservation and conservation of Biscayne Bay. The exhibition, curated by Bridge Initiative founder Katherine Fleming, features 35 local and international artists whose works cross disciplines to explore Biscayne Bay’s cultural, historical, and ecological significance.

“Amidst Florida’s record-breaking temperatures, I can’t think of a timelier art exhibition,” says Brian Sidoti, Director of The Kampong. “I am thrilled to collaborate with the Bridge Initiative as we bring the art and science communities together to give Biscayne Bay a voice.”

Biscayne Bay, a cherished subtropical lagoon stretching from North Miami to Card Sound, holds hidden histories and remarkable natural wonders. “In Biscayne, we tour the Bay’s treasures at The Kampong, one of the five botanical gardens of the National Tropical Botanical Garden that has immense historic and cultural significance for South Florida and beyond,” says Katherine Fleming, exhibition curator. “Through this multidisciplinary showcase, we aim to deepen our connection with Biscayne Bay and foster a future where nature and culture thrive harmoniously.”

Running from September 15th to December 2nd, 2023, Biscayne invites visitors to embark on an educational and visual journey that transcends art’s traditional boundaries. Visitors to The Kampong can enjoy the Biscayne exhibit included in the price of admission for a garden tour. Parking is limited and online reservations are strongly encouraged.

NTBG Internship Series: Barbara Herrera

Over half a century, NTBG has hosted hundreds of interns that have become leaders in plant-based careers. In this series, get to know a few of our former and current interns who are forging their paths in tropical plant science and conservation and creating brighter futures for generations of plants and people.

Barbara Herrera’s internship at The Kampong helped reaffirm her passion for tropical botany.

By Jon Letman, Editor

Raised in Miami’s Little Havana neighborhood, Barbara Herrera attended Florida International University where she earned a bachelor of science degree in environmental agriculture in 2020. Through one of her professors, she met Dr. Christopher Baraloto, Director of the International Center for Tropical Botany (ICTB) at The Kampong. He introduced Barbara to a citizen science collaborative tree data collection initiative called ‘Grove ReLeaf’ which led to her learning about an internship offered at The Kampong.

For two years, Barbara worked as a research assistant intern at The Kampong where she also did a tropical botany internship at the ICTB. Her work included identifying and measuring trees in the surrounding area, contributing to the creation of a food forest booklet, and other community outreach through workshops and seminars.

Currently Barbara is working toward a Master’s Degree at the University of South Florida in Tampa where she is focused on Latin and Caribbean studies which will benefit her as she pursues a career in ethnobotany in the Caribbean. Barbara spoke about her experience as an intern at The Kampong.

How did your internship relate to your previous studies?

I saw ICTB at The Kampong as an extension of the things I had already been doing and as a resource of global communication between botanists. There are so many opportunities to expand in an educational direction.

Has your experience with FIU and the ICTB at The Kampong steered you in a particular direction academically or professionally?

These communities and organizations were all linked in one way or another and it was on me to figure out what those links were. These are opportunities that were available and the tropical botany course at ICTB at The Kampong was phenomenal as it was centered around both international and local students. It definitely feels like all of these have made me a better academic and I continue to be influenced by all that I learned.

How did staff at the ICTB and The Kampong help you along your path?

Christopher Baraloto, Benoit Jonckheere, and other staff made me a more well-rounded individual. Their different approaches to horticulture and plant science, as well as their backgrounds, gave me a range of possible paths to pursue under the umbrella of plant science. They were always willing to provide suggestions that helped me make academic decisions toward my educational goals. They were, and continue to be, mentors to me.

How has your experience at the ICTB and The Kampong impacted your relationship with plants and nature?

Through the internship at The Kampong it was refreshing to learn about the ethnobotany of Hawaiʻi too. This helped reaffirm my passion for tropical botany. Ultimately, it was about the setting. Being surrounded by tropical flora 24/7 was everything to me and I grew closer to the plants around me as I interacted with them.

Do you plan to remain involved with ICTB at The Kampong in the future?

Definitely. I would love to do research based in the Caribbean, specifically the Dominican Republic. I feel like Miami is part of the Caribbean, so I see myself working with NTBG staff again. I try to stay connected with what’s going on at The Kampong as it has been a major source for friends and education for me.

Why should someone support internships at The Kampong and ICTB at The Kampong?

If I hadn’t gotten paid I wouldn’t have been able to dedicate the 40 hours a week for the internship. Also, for the tropical botany course, I was given a scholarship and that helped me by not needing to have another job. Thankfully, I have been funded as it makes it more accessible. Botany and other science fields have been neglected for too long so now I think it’s up to people with financial means to pay attention again and say, “maybe we need this field to flourish in a more substantial way.”

People need plants. Plants need you.

Plants nourish our ecosystems and communities in countless ways. When we care for plants, they continue caring for us. Help us grow a brighter tomorrow for tropical plants.

Five Ways to Give on Giving Tuesday

Everyone can have an impact on #GivingTuesday! Join NTBG on November 29 by pledging your time, skills, voice, or dollars to grow a brighter tomorrow for the tropical plants that sustain and nourish us all. Add Giving Tuesday to your calendar and be sure to follow us on social media!

Five Ways to Give on GivingTuesday

Give money

Donate to NTBG, purchase, renew or gift a membership.

Interested in making a difference year-round? For as little as $10 a month, your monthly pledge helps provide NTBG a steady stream of support no matter how uncertain the times may be. Thank you for considering this helpful option.

Give Your Voice

Speak up! Talk to your friends and family about saving plants.

Need some tidbits to share with the people in your life? If you don’t already, follow us on social to keep up with the latest! Check out our news page for updates on our work and subscribe to our newsletter to stay in the know.

Give Your Time

Volunteer or donate your skills to NTBG.

Interested in becoming a volunteer? Click the button below to explore opportunities.

Give Goods

Buy an item from the NTBG wishlist.

Purchase an item from our wish list and your donation will go directly to meet immediate program needs.

Inspire Others

Organize a fundraiser or share your story online.

Share why you support NTBG with the world! Need a place to start? Download this #unselfie template and tell your story on November 29, 2022.

Even More Ways to Give

Global biodiversity is in crisis. Today we are at risk of losing plants faster than we can discover them. Your partnership and steadfast support help us continue our science, conservation, and research efforts in Hawaii, Florida, and around the world.

Dr. Sandra Knapp Awarded 2022 David Fairchild Medal for Plant Exploration

Kalaheo, Hawaii (April 5, 2022)—The National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG) has awarded Dr. Sandra Knapp, a tropical botanist and researcher at the Natural History Museum, London the 2022 David Fairchild Medal for Plant Exploration. The medal has been awarded annually since 1999 to individuals who have demonstrated service to humanity in exploring remote areas of the world to advance plant discovery, the cultivation of new and important plants, and the conservation of rare or endangered plant species.

The medal was presented to Dr. Knapp on April 6 in a ceremony at The Kampong, NTBG’s garden located in Coconut Grove, Florida and former residence of renowned explorer and botanist Dr. David G. Fairchild.

Dr. Knapp is best known as one of the world’s leading specialists in the taxonomy, crop diversity, and ethnobotanic uses of the Solanaceae, a family that includes tomatoes, potatoes, eggplants, tobacco, and mandrakes.

Born in Oakland, California and raised in New Mexico, Sandra Knapp was introduced to field botany as an undergraduate at Pomona College in the 1970s. It only took one visit to the desert with a microscope in hand for her to realize that she wanted to dedicate her life to fieldwork and the study of plants. Sandra Knapp went on to study at the University of California, Irvine (’78-’79) before earning a PhD. from Cornell University (’85). Dr. Knapp’s doctoral dissertation was titled A Revision of Solanum section Geminata. She studied under the late Dr. M. D. Whalen who she thanks for first suggesting that she study Solanum.

Upon graduating, Dr. Knapp taught biology, taxonomy, and phytogeography as a teaching assistant at Cornell before embarking on four decades of field research, primarily in Central and South America as well as in China and Uganda.

In 1992, Dr. Knapp joined the Natural History Museum as a senior scientific officer in the Botany Department. Her career with the museum has continued and evolved from research botanist to individual merit researcher (level 2) today. She has also served as head of the museum’s Plants Division (2012-2019).

Over the course of her career, Dr. Knapp has contributed to Flora Mesoamericana and is the founder and curator of the online resource Solanaceae Source. She has described over 100 new plant species, authored more than 270 peer-reviewed scientific articles, and written, edited, or contributed to 30 scientific and popular books about plant exploration, discovery, and botany. She is the author of the forthcoming book In the Name of Plants: From Attenborough to Washington, the People Behind Plant Names (University of Chicago Press). From 2018 to 2022, Dr. Knapp has served as the president of the Linnean Society of London.

Dr. Knapp has broad experience as a field explorer, research botanist, taxonomist, educator, and active member of numerous academic and scientific bodies including appointments to the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland, Fauna and Flora International, the Field Museum of Natural History, the Harvard University Herbaria external review board, and others.

She is also an enthusiastic science communicator, editor, and author who believes that all people have the potential to be naturalists by being keen observers and thinkers engaged with the natural world and their own surroundings.

As an avid public speaker, Dr. Knapp has lectured widely for public and professional audiences and on panels for the United Nations Climate Conference, the Natural History Museum, the Royal Institution, the BBC, and other scientific and educational venues.

Dr. Knapp is a firm believer in initiating conversations about science and being open-minded to new ideas and different perspectives. She says science communications is about “having a conversation and arriving sometimes at a place that you the scientist didn’t think you would arrive at.” The important thing, she says, is to start that conversation.

One of Dr. Knapp’s colleagues, Dr. Jan Salick, senior curator emerita with the Missouri Botanical Garden, described her as a “most valued friend.” She recalled meeting Sandra Knapp while both were

attending graduate school at Cornell University. On one occasion, Dr. Salick invited Dr. Knapp to join her on a collecting expedition in the jungles of the Amazon headwaters. Dr. Salick recalls how despite both of them being pregnant at the time, they paddled on rafts and dugout canoes down Rio Palcazú and its tributaries, interviewed shamans and Indigenous women about traditional knowledge of cassava (yuca), and how Dr. Knapp found a new species of Solanum on that same trip.

Dr. Knapp was nominated for the Fairchild Medal by NTBG’s science and conservation director Dr. Nina Rønsted who described her as “passionately and deeply engaged in a plethora of areas and international organizations devoted to plant systematics, fieldwork, crop science, and more.”

Dr. Rønsted called Dr. Knapp an “inspiration to a generation of scientists, students, practitioners, and plant enthusiasts,” adding that she has contributed to a greater understanding of the importance of saving the world’s plants.

Upon learning that she had been named as recipient of the 2022 Fairchild Medal, Dr. Knapp admitted her surprise, calling the award an “incredible honor.”

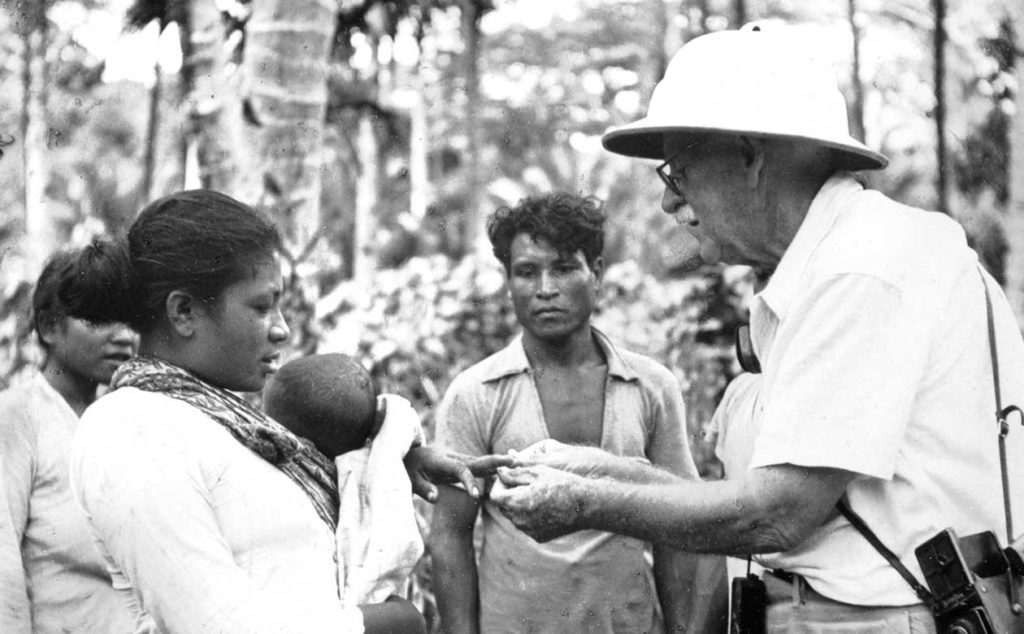

The David Fairchild Medal for Plant Exploration is named for one of the most influential horticulturists and plant collectors in American history. Dr. Fairchild devoted his life to plant exploration, searching the world for useful plants suitable for introduction into the country. As an early “Indiana Jones” type explorer, he conducted field trips throughout Malaysia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, China, Japan, the South Pacific, the Caribbean, South America, the Middle East, and East and South Africa during the late 1800s and early 1900s.

These explorations resulted in the introduction of many tropical plants of economic importance to the U.S., including sorghum, nectarines, avocadoes, hops, unique species of bamboo, dates, and varieties of mangoes.

In addition, as director of the Office of Foreign Seed and Plant Introduction of the U.S. Department of Agriculture during the early 20th Century, Dr. Fairchild was instrumental in the introduction of more than 5,000 selected varieties and species of useful plants, such as Durum wheat, Japanese varieties of rice, Sudan grass, Chinese soybeans, Chinese elms, persimmons, and pistachios.

Fairchild and his wife, Marian Bell Fairchild, daughter of inventor Alexander Graham Bell, purchased property in South Florida in 1916 and created both a home and an “introduction garden” for plant species found on his expeditions. He named the property “The Kampong,” the Malay word for “village.”

The tropical species Fairchild collected from Southeast Asia in the 1930s and 1940s are still part of the heritage collections of The Kampong. The property is the only U.S. mainland garden owned by NTBG, which has four gardens and five preserves in Hawaii. The organization is dedicated to conservation, research, and education relating to the world’s rare and endangered tropical plants.

Media contact: media@ntbg.org

National Tropical Botanical Garden (ntbg.org) is a not-for-profit, non-governmental institution with nearly 2,000 acres of gardens and preserves in Hawaii and Florida. The institution’s mission is to enrich life through discovery, scientific research, conservation, and education by perpetuating the survival of plants, ecosystems, and cultural knowledge of tropical regions. NTBG is supported primarily through donations, grants, and memberships.

Interview with Dr. Sandra Knapp, recipient of the 2022 David Fairchild Medal for Plant Exploration

Since 1999, the National Tropical Botanical Garden has recognized exceptional botanists, horticulturists, and explorers by awarding them the David Fairchild Medal for Plant Exploration.

On April 6, 2022, Dr. Sandra Knapp of the Natural History Museum (London), will be presented with the medal at a ceremony at NTBG’s Miami garden, The Kampong. Dr. Knapp is best known as a specialist in the taxonomy, crop diversity, and ethnobotanic uses of the Solanaceae, a family that includes tomatoes, potatoes, eggplants, tobacco, and mandrakes.

Dr. Knapp has over four decades of experience botanizing in Central and South America as well as Africa and China and is a contributor to Flora Mesoamericana and the founder/curator of Solanaceae Source. She has described over 100 new plant species, authored more than 270 peer-reviewed scientific articles, and has written, edited, or contributed to 30 scientific and popular books about plant exploration, discovery, and botany. From 2018 to 2022, Dr. Knapp served as the president of the Linnean Society of London.

Dr. Knapp spoke with NTBG in January from her home in London. An edited and condensed version of that conversation follows below.

NTBG: Congratulations on being named recipient of the David Fairchild Medal for Plant Exploration.

Sandra Knapp: Thank you. It was a real surprise. I thought, “What? This is crazy! There must be some mistake.” But it’s an incredible honor because David Fairchild was an extraordinary person.

You’ve spent much of your career studying Solanaceae. Why have you focused on this group of plants?

At Cornell University, my major professor Michael D. Whalen said I should study the genus Solanum and go to the tropics. I wanted to go to the desert, but I went to Costa Rica and that was it. I was completely hooked. I fell in love with the tropics and the wonderful, massive, incredible diversity that’s all around. I started looking at solanums and there were lots that didn’t have names but they were all clearly different. Nobody had worked on the taxonomy of them so I thought, “OK, maybe I can do Solanum.” There was no looking back. I just got deeper and deeper into Solanum.

What exactly attracted you to this family of plants?

The Solanaceae are amazing because they’re well-known both as things that we love to eat— tomatoes, potatoes, eggplants—but also as plants that can kill us, like nightshades and tobacco. They are inextricably linked with people. It’s just fascinating because people have found uses for so many Solanaceae. You can pick fruits and eat them. But all of these poisons, medicines, and psychoactive drugs—that requires a certain amount of experimentation which is pretty dangerous, really. It is absolutely fascinating that within this one small family there are all these uses.

The other thing that is amazing about Solanaceae is that it’s a medium-sized family that only has about 4,000 species, it’s not a monster like the daisies or the orchids. But half the species diversity of the family is composed of a single genus, Solanum, which is one of the top ten most species-rich genera of flowering plants. That’s pretty amazing. It’s one of maybe ten or fifteen genera which have more than a thousand species. Solanum, at our current estimate, will soon have 1,250 species. One of the things that grabbed me is—why are there so many of these species of Solanum? To even begin to answer that question, you need to figure out what the species are and nobody had done that since the 19th century. People keep asking “haven’t you figured it out yet?” My answer is, no, we’re getting there though.

Can you talk about the loss of biodiversity as it relates to Solanaceae?

The majority of species diversity of Solanum is in South America. So you would expect that the highest speciation rates, the highest diversification rates, would be there as well. Well, it turns out it’s the exact opposite. The highest diversification rates are in places like Australia and Africa, and they seem to be correlated with the Miocene aridification of those continents. The changing landscape helped Solanum in those areas invade new territories and have explosive speciation.

Climate change and environmental change can work both ways. Aridification is often bad for plants, but it depends on the plant. The lineage of Solanum that made it to Australia is very dry- adapted and it just went berserk and diversified. Still not as many species as in South America, but they’re all each other’s closest relatives. Then there are other species which have very narrow ranges, in the páramos and other high areas in the Andes, where the tree line is going up and so those species are at risk from climate change. But actually, the biggest driver of change is us, it’s humans—our modification of the landscape.

What about the loss of traditional plant knowledge?

A lot of the traditional knowledge about Solanaceae is actually global traditional knowledge now because these are world-wide crops and much is widely known. There is traditional knowledge about Solanaceae that I know nothing about. I am sure that there is also traditional knowledge that is held by very few people. But as Indigenous peoples become threatened themselves, and as languages become threatened as well, a lot of that plant knowledge is bound up in the language and when language becomes at risk, then the knowledge becomes at risk.

The coronavirus pandemic has had a profoundly harmful impact on people around the world. It has also disrupted so much of our personal and professional lives. Can you find any kind of silver lining in this?

One of the silver linings is that with regards to herbaria and collections, it’s becoming clearer that if your collections are online, people will use them. That’s always kind of been true, but when we’re all stuck at home, trying to do our work at home, having literature online through the Biodiversity Heritage Library and having herbarium specimen images online is an absolute godsend. That didn’t come with the pandemic, but I think the pandemic has provided impetus for people to accelerate digital access.

Regarding the pandemic, as it relates to the understanding and the importance of preserving plants, how do you make a connection?

I actually think that the pandemic, and the fact that it is the result of an interaction between humans and the natural world, makes it ever more important that we study, understand, and preserve the natural world so that there are places for nature to thrive. Human beings are an invasive mammalian weed. We are the epitome of a weedy species. We go everywhere. We grow everywhere. We reproduce fast. We can adapt to all kinds of climates and places. We’re the most successful weed on the planet. If you think about human beings as a weed, weeds are a threat. Human beings are a threat. And when weeds come in contact with particular pests or can pick up genes that are problematic, then it becomes a problem. The same is true with viruses and us. This is hardly a surprise, to be honest.

Do you think scientific organizations, botanical gardens, museums, or the media in general are doing a good job of communicating the importance of science, and plants in particular?

I think this is one of the things that we all struggle with, and all of us are trying and doing as best we can, but I think there are many things we could do better. One of those is having a conversation rather than just giving information, because bringing people along is about acknowledging that they have views that might be different from our own and being open to that conversation. One thing that often happens in science education is people think of it as a one-way street. “We will communicate our science to this public and then they will understand.” Well, it doesn’t work like that. It’s much more about having a conversation and arriving sometimes at a place that you, the scientist, didn’t think about at the onset.

Also, being willing to say that you’re wrong or that you don’t understand or don’t know is crucial. I think as scientists—and I know I do this—it’s almost as a knee-jerk thing to avoid this, I worry about saying something because I might be wrong. But actually, that doesn’t matter. The really important thing is to start a conversation, because that’s where you begin to look at the world through somebody else’s eyes and that then changes your own world view.

Science itself can’t exist in a vacuum because science is part of society. It doesn’t exist as separate from society. Some people might consider advocacy about climate change to be political. What’s considered political is really, in a way, a matter of opinion. Scientists are part of society, and they need to be concerned with societal issues. And sometimes it can be quite uncomfortable.

Can you talk about how you communicate science at the Natural History Museum?

I am proud of my own institution for creating a strategy which is about creating advocates for the planet. Yes, we do good science and yes have great collections—but our mission is to create advocates for the planet. We use our collections and the science we do with them to do that. People who are vocal supporters of the natural world is our long-term goal.

You mean to get everybody involved?

Everybody’s a natural historian, really. Everybody is interested in pebbles and things that they pick up as they walk around their neighborhoods. But it can be frowned upon in scientific circles because it’s not “scientific.” But actually, it is scientific. If you go out in the forest and collect a plant, you make a hypothesis that it might be ‘species X’ and then you use evidence to disprove that or perhaps that evidence supports your idea. Somehow this has been lost, the fact that natural history—just observing and documenting the world around us—is hypothesis-driven.

You are just the third woman to receive the Fairchild Medal. What are your thoughts on this imbalance?

I’ve been compiling the gender statistics for the medals for the Linnean Society, it’s actually quite shocking. Mostly men get nominated so it’s not really surprising that medals often go to men, but why is that? I don’t know. The times are changing. I am the third female president of the Linnean Society which dates from 1788 so I am the 53rd president, or something like that. But only the third woman, but my successor is also a woman, so change is happening. What I think will be really interesting is if we can look back in twenty years’ time and see if the graph of medal awards changes. What we should be is fifty-fifty, really. Excellence doesn’t have gender.

Can you talk about how field work has changed since you first started as a botanist?

People don’t go in the field by themselves anymore. We go into the field with a colleague or with our local counterparts, say from an institution from South America or in Africa. I think that’s a really good thing because when you do, relationships begin with local scientists from those countries which then levels up science and allows people to share in a much more equitable way than happened in the past. Parachute science, where collectors and explorers went in and took, as happened in colonial times, certainly should be a thing of the past.

Last question. Do you think the botany and natural history of Central and South America offer an avenue for increased interest and a greater understanding for that part of the world?

Yes, the Americas are an absolutely extraordinary set of continents and understanding their sheer diversity is part and parcel of understanding the world. Many of our crops come from Eurasia, but others are American in origin. Thinking about centers of crop plant origin is interesting in this context because if you look at crop plants that are essential to diets in the United States, they’ve all—except for the sunflower—come from outside of North America. If you took everything that didn’t originate in the United States, you’d be left with very little; David Fairchild had a real hand in this diversity of crops in the United States that now seems to be integral to US agriculture.

Globalization is often perceived as a really bad thing, but it has gotten us to where we are and it has been happening for a long time—long before European colonization of the Americas. For me it presents a huge and uncomfortable paradox. How can we accept the fact that the foods that we eat, the food that we love, the foods that we think of as being indigenous to ourselves, actually come from somewhere else, but then, at the same time, not accept people from those other places. Why is it “food good, people bad”? It’s very Animal Farm-y and kind of Orwellian in a slightly odd way.

Our diets across the globe are becoming much more diverse so we’re eating lots of different things. But we’re all, across the world, eating much more of the same things. So regionalization of diets is disappearing but we’re all eating more different things in part because of the ease of transport and global markets and all this other stuff. It may all change if we’re unable or unwilling to transport snow peas from Kenya or cherries and apples from Chile in the non-apple season for the northern hemisphere, as global events and our concern for the climate coincide.

Plant Hunters Secure Biodiversity Hotspots

Looking to the Past to Protect Flora of the Future

To protect the food of the future, humans must learn from the past. A secluded garden in Florida preserves a 19th-century culinary curator’s tall tales and botanical introductions, while modern-day NTBG plant hunters in Hawaii use advanced technology to document and save species in biodiversity hotspots. With your help, NTBG is stemming the tide of plant loss and food insecurity. When you donate to the National Tropical Botanical Garden, you’re a part of this critical work that keeps our plants and our planet healthy.

It’s hard to imagine in today’s social media-induced foodie frenzy that the American diet has been anything other than a cultural melting pot of culinary curiosities. However, as Author Daniel Stone writes in his 2018 novel, The Food Explorer: The True Adventures of the Globe Trotting Botanist Who Transformed What America Eats, the same way immigrants came to our shores, so too did our food.

Before the 20th century, much of what America ate was meat, seafood, leafy greens, beans, grains, and squash – nutritious and hearty, but hardly the colorful, flavorful fruits and vegetables easily acquired from grocery store shelves and farmers markets today. Surprisingly, we have one adventurous, botanizing plant hunter to thank for most of the introduced tropical fruit, nuts, and grains that have become prominent parts of the American diet, and he is closely connected to NTBG.

David Fairchild was one of the world’s leading plant collectors in the early 20th century. His private residence in Coconut Grove, Florida, is the present-day location of NTBG’s Kampong Garden. With heritage collections of numerous Southeast Asian, Central, and South American fruits, palms, and flowering trees, The Kampong protects Fairchild’s horticultural legacy and many of his original introductions to the US. It also provides a window into the past that inspires today’s plant hunters and food protectors working toward a more resilient future for our plants and planet.

“The greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add a useful plant to its culture.”

Thomas Jefferson

Fairchild, David Fairchild – International Plant Spy and Man of Botanical Intrigue

David Fairchild was born in the late 19th century and grew up in reconstruction-era America. At that time farmers made up most of the country’s workforce and economic opportunity outside of agriculture was sparse. With a fragile post-war economy largely dependent on farming, The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) feared that an invasive species or natural disaster could easily disrupt the nation’s food supply and created a plant pathology division aimed at diversifying the nation’s agricultural offerings.

Fairchild joined the division after receiving his education in horticulture and botany from Kansas College, and traveled the world as part government food spy, part horticulturalist, part adventurer seeking new food and crops for the expanding American economy and diet. After several years of botanical escapades across Europe, Southeast Asia, Central and South America, he became the chief plant collector for the USDA and led the Department of Seed and Plant Introductions vastly increasing the biodiversity of the nation’s food crops.

Fairchild’s Legacy Today

Chances are, at least one of the beverages or meals you consumed today would not have been possible without Fairchild’s introductions. Avocado, mango, kale, quinoa, dates, hops, pistachios, nectarines, pomegranates, myriad citrus, Egyptian cotton, soybeans, and bamboo are just a few of the thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of plants Fairchild introduced to the United States.

“Fairchild was key to the development of agricultural research and introduction stations around the US and in Puerto Rico. Many of those stations are still current and viable, acting as gene banks for plants he brought into the country,” said Craig Morell, Director of The Kampong. “The Kampong houses some of his early introductions, but these were mostly plants he liked to have in his personal garden. We maintain them today in the same fashion that museums curate and preserve antiquities,” Morell continued.

“Fairchild was key to the development of agricultural research and introduction stations around the US and in Puerto Rico.”

Craig Morell, Director of The Kampong

Fairchild’s work fundamentally changed the American diet and agricultural economy, and his career as a plant hunter, gene banker, and horticulturalist continues to inspire those following in his footsteps today.

Modern-Day Plant Hunters Protect Biodiversity Hotspots

Hawaii was selected for NTBG’s headquarters because of its status as a biodiversity hotspot. This means that while rich in biodiversity, Hawaii’s flora and fauna are deeply threatened by climate change, invasive species, and human activity. While the rate of species loss continues to accelerate worldwide, 2020 was a banner year for NTBG’s modern-day plant hunters. Our team of scientists discovered previously unknown populations of nine rare and endangered species including, Hibiscadelphus distans; Melicope stonei; Schiedea viscosa; Lysimachia scopulensis; Lepidium orbiculare; and Isodendrion laurifolium. Bolstering biodiversity hotspots not only strengthens our food supply, it also builds resilience and ensures ecosystems continue to sustain life, supply oxygen, clean air and water.

“These discoveries offer new hope for conservation of Hawaii’s endangered rare plants and native forests,” said Nina Rønsted, NTBG Director of Science and Conservation. “These findings also illustrate the importance of investing in science as a vital tool to better understand and protect the natural world,” she continued.

Like Fairchild, today’s plant hunters are no strangers to thrill and adventure. NTBG botanists have long been known for repelling down sheer cliffs and into steep valleys searching for rare plant life. Today, with the help of drone and mapping technology, NTBG remains at the forefront of tropical plant discovery and conservation.

“Hawaii has been referred to as the extinction capital of the United States,” said Ben Nyberg, NTBG GIS specialist and drone pilot. “It’s home to 45% of the country’s endangered plant population, and we don’t know how climate change and new threats like Rapid Ohia Death will affect these rare plants’ habitats. We are trying to document and collect material as quickly as possible,” he finished.

“These discoveries offer new hope for conservation of Hawaii’s endangered rare plants and native forests.”

Nina Rønsted, NTBG Director of Science and Conservation

Keeping Watch

NTBG sets itself apart in the race to save rare and endangered tropical plants. In addition to collecting, categorizing, and seed banking rare plant material, NTBG outplants thousands of rare and endemic species into our gardens and preserves located across the Hawaiian Islands.

From now through 2022, NTBG will engage in a conservation project called, Securing the Survival of the Endangered Endemic Trees of Kauai supported by Fondation Franklinia. This project will focus on eleven species that either previously grew in the Limahuli Valley or have a remnant population of fewer than ten individuals. Throughout the three-year project, NTBG will collect and propagate seeds and use previous collections from our seed bank to balance the need for substantial seed collection. When the new treelets are strong enough, most will be outplanted in the Limahuli Preserve to monitor and protect them. Alongside the Fondation Franklinia project and with the help of our supporters and collaborators, NTBG remains dedicated to saving as many endangered plant species as possible as we work to protect and restore native ecosystems on Kaua‘i and beyond.

From the outlandish adventures and introductions of a 20th-century plant hunter to modern-day scientists using drones to seek out rare plant life on the steep cliffs and rocky ridges of Kauai, NTBG is learning from the past and leading the way in the fight to protect the future of food, plants, animals, and ecosystems. Learn more and support plant-saving science today.

Healthy Plants. Healthy Planet.

NTBG is a nonprofit organization dedicated to saving and studying tropical plants. With five gardens, preserves and research centers based in biodiversity hotspots in Hawaii and Florida, NTBG cares for and protects the largest assemblage of Hawaiian plants. Join the fight to save endangered plant species and preserve plant diversity today by supporting the Healthy Plants, Healthy Planet campaign.

Simple Banana Recipes

We are sharing a few simple banana recipes you can make and share this holiday season. These dishes were adapted from Hawaiian Cookbook by Roana and Gene Schindler. Buy ingredients from your local farms and farmer’s markets when possible to make these dishes even better!

Share your completed dishes with us on social media! Be sure to tag @ntbg on Instagram.

Banana (Maia) Pudding Recipe

Ingredients

- 2 cups coconut milk (or cow’s milk)

- 2 tablespoons sugar

- 1/4 cup raisins (optional)

- 1 tablespoon chopped macadamia nuts

- 3 medium-size ripe bananas, mashed

Cooking Instructions

- Step 1: Scald milk in the top of a double boiler or thick-bottomed saucepan.

- Step 2: Once the milk is scalding, add sugar, raisins, nuts, and bananas. Cook for 10 minutes, stirring constantly until mixture thickens. Remove from heat.

- Step 3: Divide into individual serving dishes, distributing fruit evenly. Cool and refrigerate. Serve with a dollop of red jam, jelly, or whipped cream. We topped with Papaya Vanilla Jam from Monkeypod Jam, a small preservery and bakery located on Kauai.

Drunken Bananas (Maia Ona) Recipe

Ingredients

- 6 small, firm bananas

- 1/2 cup rum mixed with 2 teaspoons lemon juice. We used Kōloa Kauaʻi Spice Rum

- 1 egg, beaten

- 3/4 cup flaked coconut or chopped nuts (almonds, macadamia, walnuts)

- Neutral oil for frying like vegetable oil

Cooking Instructions

- Step 1: Soak whole bananas in rum and lemon juice for about 1 hour. Turn frequently.

- Step 2: Dip bananas in egg and roll in coconut or chopped nuts.

- Step 3: Heat 1/2 inch of oil in a skillet on low and fry bananas slowly until brown on all sides and tender. Drain on paper toweling and serve hot.

Share your completed dishes with us on social media! Be sure to tag @ntbg on Instagram and use the hashtag #ntbgrecipechallenge for a chance to win a prize.

Banana History

Banana or maiʻa in Hawaiian are canoe plants introduced and planted in some of the most idyllic and enchanting places throughout the islands. One ancient story described a banana patch so large you could get lost trying to find your way around it growing deep in Maui’s Waihoi Valley. The story caught the attention of naturalist Dr. Angela Kay Kepler in 2004, and a botanical adventure ensued. Determined to find the legendary banana field, Dr. Kepler hired a helicopter to survey the valley. Sure enough, growing along the Waiohonu River banks, was the largest wild-growing traditional Hawaiian Banana Patch.

After making this discovery, Dr. Kepler phoned Kamaui Aiona, former director of NTBG’s Kahanu Garden and Preserve, managing a small collection of banana varieties. The two returned to the wild patch, collected a pair of young specimens, and returned them to the garden collection where they are still growing. Today, Kahanu’s maia collection exceeds 30 varieties and is one of the most diverse in the State of Hawaii. This collection is essential to the safeguarding the world’s most popular tropical fruit.

Strength in Numbers

A rare collection of bananas at Kahanu Garden safeguards species diversity and the world’s favorite tropical fruit

The world’s most popular tropical fruit is one of the most susceptible to disease. NTBG’s Kahanu Garden maintains a collection of rare bananas that is a safeguard preserving plant diversity of this important tropical food crop and your breakfast. With your help, NTBG is stemming the tide of plant loss and food insecurity. When you donate to the National Tropical Botanical Garden, you’re a part of this critical work that keeps our plants and our planet healthy.

It is a story that is all too common in 2020. A mysterious disease quietly spreads far and wide before its life-threatening symptoms appear. By the time the disease is identified, it’s impossible to stop and takes a heavy toll. While familiar, this story is not about the present COVID-19 pandemic but rather a fungus wreaking havoc on banana crops worldwide and threatening the existence of the most widely consumed Cavendish variety.

If you ate a banana today, chances are you were able to easily acquire it from a local supermarket or cafe. It probably looks and tastes just like every other banana you have ever purchased, and you could find one just like it from nearly any grocer or roadside fruit stand on the planet. This is because monoculture crops of Cavendish bananas account for 47% of global banana production and 99% of bananas cultivated for commercial export.

Monoculture is a form of agriculture focused on growing one type of crop at a time. In the case of Cavendish bananas, not only are they the primary variety cultivated for commercial consumption and trade, the crops are genetically identical. This means that every Cavendish banana you have eaten is a clone of one that came before it. While monoculture does offer the benefit of efficiency and scale, it also increases the risk of disease and crop vulnerability. In other words, if a disease affects one plant, it can affect them all. Banana farmers and barons of the early 20th century are no stranger to the vulnerabilities of banana monoculture. Until the mid 20th century, the Gros Michel variety of banana was the most popular, commercially available variety. Still, fungus all but wiped it out in the 1950s, replaced by today’s heartier, or so thought, Cavendish variety.

A race with no end in sight

Tropical Race 4 (TR4), also known as Fusarium Wilt or Panama Disease, is a soil-borne fungus that enters banana plants from the root, blocks water flow throughout the plant, and causes it to wilt. At present, TR4 cannot be controlled with fungicide or fumigation and has been found in banana-growing regions across Asia, Africa, Australia and was discovered in South America, where most commercial bananas are produced in 2019.

Bananas are the world’s most popular tropical fruit. In fact, the average American consumes more than 26 pounds of banana every year. While not exactly a staple of the American diet, bananas are one of the most economically important food crops worldwide and responsible for an annual trade industry of more than $4 billion, only 15% of which is exported to the United States, Europe, and Japan. What is particularly devastating about the fungus’ potential to overrun our most popular variety is that most bananas are consumed by people in developing countries where affordable food sources and nutrient-rich calories can be hard to come by. With a great demand for bananas and monoculture crops highly susceptible to TR4 and other fungi, scientists are racing the clock to develop new disease-resistant bananas, but looking to history is likely where the answer lies.

Bananas with a legendary past and promising future

Long before westerners arrived in Hawaii, ancient Polynesians voyaged to the islands in double-hulled sailing canoes. To sustain life throughout their journey, and once they reached their destination, they brought a selection of at least two dozen species of plants for food, clothing, structure, medicinal and cultural purposes. These plants are commonly referred to as “canoe plants,” and even though they were introduced to the island, they are an essential part of Hawaii’s cultural history.

Banana or maiʻa in Hawaiian are canoe plants introduced and planted in some of the most idyllic and enchanting places throughout the islands. One ancient story described a banana patch so large you could get lost trying to find your way around it growing deep in Maui’s Waihoi Valley. The story caught the attention of naturalist Dr. Angela Kay Kepler in 2004, and a botanical adventure ensued. Determined to find the legendary banana field, Dr. Kepler hired a helicopter to survey the valley. Sure enough, growing along the Waiohonu River banks, was the largest wild-growing traditional Hawaiian Banana Patch.

“The number of early varieties is a fraction of what it once was, and research to verify each is ongoing. Kahanu Garden serves as a haven where they can be preserved and shared for future generations.”

Mike Opgenorth, Kahanu Garden Director

After making this discovery, Dr. Kepler phoned Kamaui Aiona, former director of NTBG’s Kahanu Garden and Preserve, managing a small collection of banana varieties. The two returned to the wild patch, collected a pair of young specimens, and returned them to the garden collection where they are still growing. Today, Kahanu’s maia collection exceeds 30 varieties and is one of the most diverse in the State of Hawaii.

“In recognition of the threat of losing indigenous crop diversity, NTBG recently adopted a strategic goal to collect and curate all extant cultivars of Hawaiian canoe plants,” said Mike Opgenorth, current Director at Kahanu Garden. “The number of early varieties is a fraction of what it once was, and research to verify each is ongoing. Kahanu Garden serves as a haven where they can be preserved and shared for future generations.” he continued.

Feeding the world starts at home

Today, Kahanu Garden is carrying on the critical work of protecting banana diversity and Hawaii’s botanical heritage and re-introducing these important varieties to local food systems. “Existing commercial varieties do not exhibit the resiliency to combat these new diseases,” said Opgenorth. “It is so important that other banana varieties remain available so that we can defend irreplaceable genetic diversity that will help feed the world,” he finished.

Feeding the world starts at home for NTBG and Kahanu Garden. Together with partners at Mahele Farm, the organizations are working together to provide for the isolated Hana Maui community and share the traditional plant knowledge of Hawaii’s kupuna (elders).

“Over the past ten years, weʻve launched ourselves into the Hawaiian-style study of maia,” said Mikala Minn, Volunteer Coordinator at Mahele Farm. “As small farmers dedicated to feeding our community, the crop variety was a perfect fit for our weekly food distributions. As we shared the fruit and learned the best ways to prepare each type, stories from our kupuna came to light. This personʻs papa would put them in the imu, half-ripe. Another kupuna grew up eating them boiled and mashed. Others made poʻe, a kind of maiʻa poi.,” he continued. Mahele Farm distributes approximately 50 pounds of fresh produce to kupuna at the Hana Farmers market every week and helps maintain a small collection of Hawaiian bananas at the Hana Elementary school.

“This personʻs papa would put them in the imu, half-ripe. Another Kupuna grew up eating them boiled and mashed. Others made poʻe, a kind of maiʻa poi.”

Mikala Minn, Volunteer Coordinator at Mahele Farm

Today’s agricultural and botanical problems are complex, but looking to the past, protecting plant diversity, and encouraging local farmers, schools, and even home gardeners to diversify is an excellent and effective step in the right direction.

Healthy Plants. Healthy Planet.

NTBG is a nonprofit organization dedicated to saving and studying tropical plants. With five gardens, preserves and research centers based in Hawaii and Florida, NTBG cares for and protects the largest assemblage of Hawaiian plants. Join the fight to save endangered plant species and preserve plant diversity today by supporting the Healthy plants, healthy planet campaign.

.svg)