Plant lovers inherently appreciate beauty. We marvel at the arc of woody stems, the gentle curl of a leaf, or the way sunlight penetrates flower petals to reveal unexpected colors. The observation of plants is visually captivating and intellectually instructive whether we are arranging flowers at the kitchen sink, examining a stately tree in a garden, or collecting the seeds of an endangered shrub.

When we admire plants online, the internet offers up a flurry of photos, videos, and images that we click through like an old-fashioned movie projector. Increasingly, technology allows us to manipulate, enhance, and improve images with a few mouse clicks to create “picture perfect” photos of flawless flowers and plants that “pop.” In doing so, however, we run the risk of overlooking the centuries-old tradition of botanical illustration.

But in the world of botany, scientists and students, collectors and curators not only still appreciate, but absolutely depend on hand-drawn illustrations, paintings, and other traditional plant renderings.

At NTBG, we greatly value the importance of preserving and using historical botanical artwork in books and print collections. At our Botanical Research Center on Kauai, The Sam and Mary Cooke Rare Book Room houses our botanical art collection, including a complete set of the Banks Florilegium. We also host botanical illustration workshops at The Kampong in Miami and at NTBG headquarters where we help foster and exhibit the art of the NTBG Florilegium Society.

In an attempt to underscore and explain its timeless beauty and scientific value, we’ve asked our staff and partners to share their thoughts on why botanical illustration matters.

“Botanical illustration serves as a connection between art and science and, in fact, is firmly planted in each discipline. As an addition to herbaria, it provides a detailed description of the species, whether as a pen and ink illustration or a richly colored watercolor, highlighting and magnifying hidden details and presenting them in an easily understood visual format. The illustrations give life and a three dimensional quality that contrasts and compliments the dried plant specimens found in herbaria.” —Tim Flynn, NTBG Herbarium Collections Manager

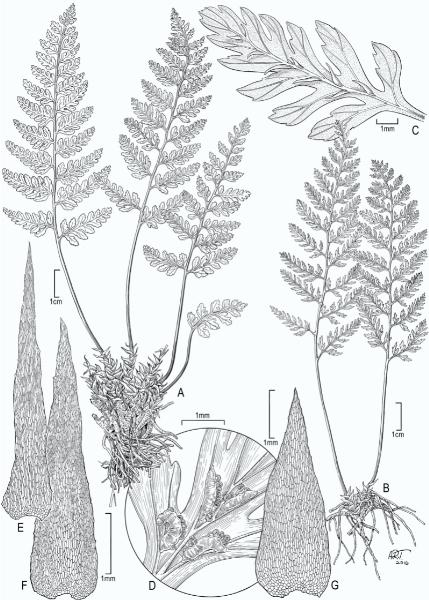

“Botanical illustration is an important aspect of plant science for a number of reasons. The illustrator emphasizes the important or diagnostic characters of a plant for the viewer. This is particularly true for pen-and-ink line drawings, which are generally used to illustrate or supplement descriptions of new plant species.

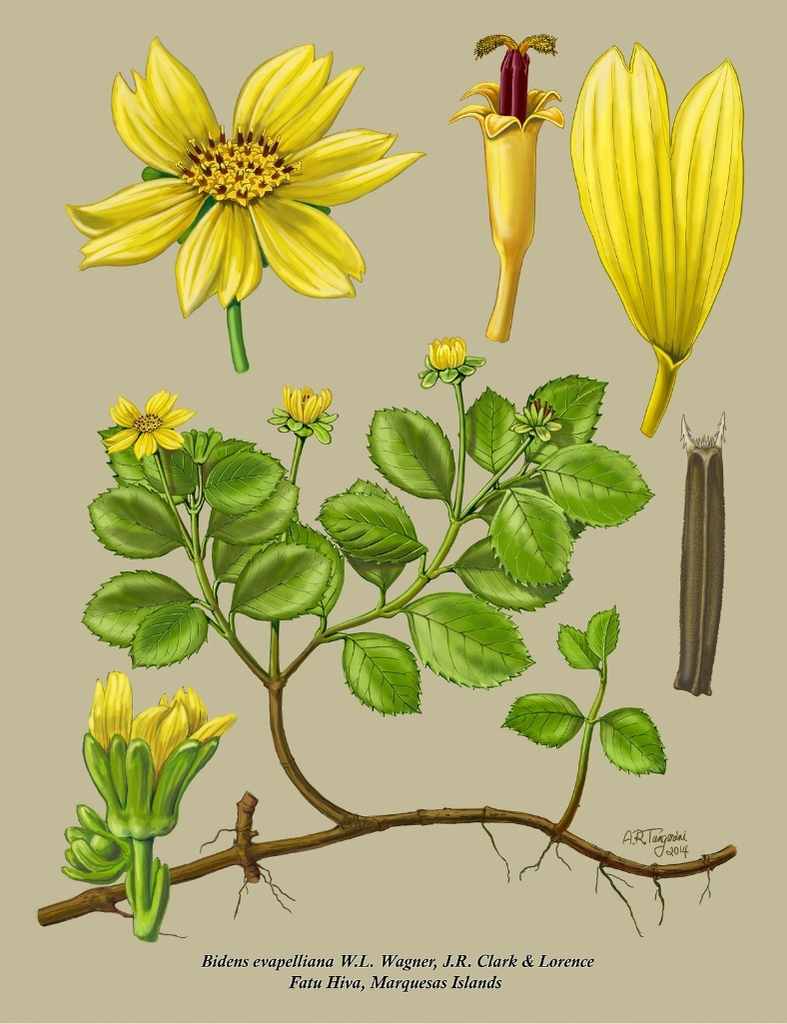

Indeed, the illustrator may see details that the botanist misses. Line drawings give the general aspect or habit of a plant, plus details of essential characters such as veins, pubescence or hairiness, flowers, fruit, and seeds that are magnified or shown in longitudinal or cross sections. These black and white line drawings may appear two-dimensional and flat, since they are usually drawn from dried, pressed herbarium specimens.

Another type of illustration is the florilegium style, usually done in watercolor or color pencil. This brings vibrant, lifelike color to the plant being illustrated and varies with each artist’s personal style. Details such as a close-up of the flowers or seed, a cross section of the fruit, a sketch of the habitat, growth habit of the plant, and even associated organisms such as herbivorous insects or pollinating birds or butterflies may be included in the illustration.

A botanical illustration can preserve a plant species, variety, or cultivar in books and journals almost in perpetuity, even if it goes extinct in the wild. Such was the case with a critically endangered Hawaiian endemic genus and species, Kanaloa kahoolawensis, first discovered and published only two decades ago but now known only from two plants in cultivation. Finally, illustrations can also help conservation efforts by creating public awareness and empathy for plants.”—Dr. David Lorence, NTBG Senior Research Botanist

“Explained simply, botanical illustrators and their works serve the scientist. They depict what a botanist describes, acting as the proofreader for the scientific description. Digital photography, although increasingly used, cannot make judgements about the intricacies of portraying the plant parts a scientist may wish to emphasize and a camera cannot reconstruct a lifelike botanical specimen from dried, pressed material.

Although illustrators now make greater use of digital research material and use the computer for digital illustrations, the thought process mediating that decision of every aspect of the illustration lives in the head of the illustrator. Whether pen and ink, pencil, watercolor, or the stylus on a drawing monitor, the tools only move at the discretion of the illustrator.

Historically, the illustration process follows the language of the scientist. Illustrators adapt media, presentation, and drawing styles to serve with current trends in scientific writing and to facilitate documentation of the scientific literature. However, the illustrator also has an eye for the aesthetics of botanical illustration, knowing that a drawing must capture the interest of the viewer to be a viable form of communication. Attention to accuracy is important, but excellence of style and technique used is also primary for an illustration to endure as a work of art and science.” —Alice Tangerini, Staff Illustrator at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, Department of Botany

I don’t simply copy how a plant looks but must explain plants through my drawing.

Wendy Hollender, Botanical Illustrator, Instructor, and Author

“The aesthetic beauty of botanical illustration has fascinated and inspired people for centuries but beyond its visual appeal, botanical drawings help identify and understand plants in a timeless manner. Its original purpose was to aid in plant identification for medicinal and culinary uses. Over the centuries, as the discipline developed, botanical illustration has proven itself invaluable in identifying newly discovered plants.

Carl Linnaeus, known as the father of modern taxonomy, and botanical illustrator Georg Dionysius Ehret, famously used botanical illustration to classify and describe the structure of plants. In the early nineteenth century, Belgian painter and botanist Pierre-Joseph Redouté captured the magnificent plants in the garden of Napoleon Bonaparte and Empress Joséphine de Beauharnais.

As a botanical illustrator, I don’t simply copy how a plant looks but must explain plants through my drawing. Botanical illustrations must reveal a plant’s morphological structure such as the arrangement of reproductive parts, leaves, and stems with a three dimensional quality.

Botanical illustration attracts and compels us. A pretty flower is not just a pretty flower, it has a specific purpose: to attract a pollinator. The flower’s visual appeal comes from colorful markings and its enticing scent lures the pollinator to the nectar within.

The scientific study of plants is essential for dealing with environmental changes, containing the spread of invasive plants, and saving endangered species, all issues addressed through botanical illustration. Although science has focused mostly on black and white pen and ink drawings, color can be used as well provided the artist capture a plant’s important structural elements.

What I find most alluring about botanical art is its seductive quality — drawing me in, feeding my desire to linger inside the mysterious center of the flower, looking through its leaves to another flower like an insect fluttering from blossom to blossom. Imbued with beauty and color, the botanical illustration seduces and attracts.”

—Wendy Hollender, Botanical Illustrator, Instructor, and Author

A botanical artist can tell the whole story of the plant

Sarah Roche, Botanical Artist, Teacher, and Education Director

“A botanical illustration is not primarily judged on its artistic beauty, but on its scientific accuracy. It must portray a plant with enough precision and detail for it to be recognized and distinguished from another species. The beauty of the drawing or painting is secondary to its scientific accuracy, but, in the hands of a talented botanical artist the illustration can go far beyond its scientific requirements.

Photography can help inform but only drawing can emphasize the detail. A botanical artist can tell the whole story of the plant: what it looks like at any stage of its life cycle and in every season. Important details can be added at different magnifications so that the important features of the subject, not shown simultaneously in nature, can be displayed together to tell the whole story of the plant.”

—Sarah Roche, Botanical Artist, Teacher, and Education Director, Wellesley College Botanic Garden

“The tradition and practice of incorporating botanical illustration, watercolor, and other media into the process of describing new plant species continues to be a rich and profound contribution to the science of botany. For many, the written diagnosis or description of a species, although exacting and artistic in its own right, is often quite dull and lifeless. For me, time and time again, it is the manuscript’s botanical art contribution that brings to life the uniqueness and sublime diversity of the species being described.

The botanical art itself becomes a lens for the viewer to see deeper into the divine artistry of a plant’s form and evolution, which in most cases helps define the key parts that render the species new to science. It is true that well-taken photographs could suffice in displaying the unique qualities of the plant being studied, but for many it is the botanical artist’s rendition that is preferred and brings us closer to the subject.

What attracts us to botanical art? Perhaps it is the combination of careful attention to detail, along with the arduous internal human process of transforming a species’ visual likeness and character through the filter of mind and soul. Meticulously stirred together with the artist’s love for nature, the image flows through hands, communicating the importance and beauty of an ancient creation only newly described.” —Ken Wood, NTBG Research Biologist

This article was originally published in The Bulletin of the National Tropical Botanical Garden, Fall/Winter 2017